Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement

Part List

Introduction - Click Here

Part 1: Explaining Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement: IQ Theories - Click Here

Part 2: Sociological Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement: Cultural Deprivation - Click Here

Part 3: Sociological Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement: Cultural Difference

Part 4: Sociological Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement: Material Economic Differences - Click Here

Part 5: Sociological Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement. Some More Recent - Click Here

Part 3:

Sociological Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement: Cultural Difference

From the 1970s onwards several other sociologists such as Willis, Brown, Bourdieu and Ball continued to claim that, in various ways, social class differences in subculture were still important influences on educational achievement but these theorists wished to emphasise that they rejected theories based upon the assumed cultural deprivation of the working class while nevertheless accepting that there were important cultural differences as between the social classes. As examples of this approach I provide a little introductory information on studies by Willis, Brown, Bourdieu and Ball although, unfortunately, it is quite impossible to do justice to the complexity and insight of these studies in the brief summaries provided here.

Paul Willis: Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids get Working Class Jobs [1977]

By the late 1970s Willis was still emphasising in his study “Learning to Labour; How working class kids get working class jobs” that working class culture was a key factor in explaining the relative underachievement of working class pupils. In his study “The Lads” (12 working class, non-examination pupils in a Midlands Secondary Modern school) were educationally unsuccessful because their working class culture led them to reject actively the types of occupations for which educational qualifications were necessary and to seek actively the unskilled, physically demanding, manual occupations for which educational qualifications were unnecessary but which they believed would confirm their own tradition -based sense of masculinity. Contrastingly the lads’ patriarchal view of the world led them to see careers in non-manual work as suitable primarily for women and this alone was sufficient for them to dismiss such careers out of hand.

Throughout the study the working class culture of the lads is presented as vibrant and exciting rather than as culturally deprived and Willis also credits the lads for their realisation that at the time Secondary Modern schools were offering a second class education and second class qualifications [CSE level qualifications] which in any case were unlikely to lead to much career advancement so that their rejection of schooling was easily understandable. It is understandable also when these boys reject the authority of their teachers since they are in their own eyes being compelled to undertake “educational” tasks which they see as essentially pointless. Indeed the main objective of one boy in the study was to complete his final year of schooling without writing a single word, an objective which he came fairly close to achieving ! . Furthermore when a mother received a letter from the school’s headmaster informing here that her son was to be suspended temporarily form school because he had returned to afternoon school in a drunk and disorderly condition, she responded by telling her son that she would be keeping the letter as an indication to future grandchildren that her son had certainly been “a bit of a lad” in his youth. An interesting but not necessarily typical working class response, I believe.

Despite its many insights, several possible criticisms have been made of Willis‘ work although he does show himself to be aware of most of them. For example, the lads’ claims about their leisure exploits based around heavy drinking, violence and sexual conquest are almost certainly exaggerated; the lads are a fairly small % of their year group and insofar as this anti- school culture exists, it may apply only to a minority and not explain why many other more conformist working class pupils still fail. Also the study is based on a small and possibly unrepresentative sample: there may be variation from school to school, and area to area and the introduction of widespread comprehensivisation could possibly be expected to change working class attitudes to education in the future. Willis admits all of this and hopes merely that his analysis will prove useful even if it does need adaptation to meet changing circumstances. Of course, he also did not predict the introduction of the GCSE which ended the distinction between high status GCE qualifications and lower status CSE qualifications.

Willis‘ description of the education process as it operated in this particular school for non-examination pupils may have been entirely realistic but if so, it presents a very dark picture. Examination qualifications are seen as value-less; progressive education is merely another more subtle strategy of social control; all teachers are seen by the lads as their enemies. Equally, Willis presentation of parts of working class culture is a dark one. Parents and children regularly swear at each other; parents often (not always) appear unconcerned with their children’s education or with their future prospects; men working on the factory floor are regularly involved in various forms of horse play in order to deaden the monotony of factory work.

However, the study is clearly a product of its times. It was carried out in the 1970s in one particular, not necessarily representative boys Secondary Modern school and since then we have seen the widespread replacement of secondary modern and grammar schools by comprehensivisation and significant changes to the industrial structure have reduced the availability of unskilled manual work suggesting that even among relatively rebellious pupils attitudes to education and employment would have to change eventually. Or would they?

Phillip Brown: Schooling Ordinary Kids: Inequality, Unemployment and the New Vocationalism.1987

Phillip Brown’s study is based on three schools in a primarily but not entirely working class town in Wales. It focuses on differing attitudes to education among working class children rather than solely on the attitudes of the rebellious minority investigated in the Willis study and also considers the likely impact of the rise in unemployment in the 1980s on attitudes to education among a sample of Welsh pupils who would be having to come to terms with the very high rates of youth unemployment existing at the time.

In the early stages of his book, Brown refers in some detail to the work of both David Hargreaves and Paul Willis, arguing that both writers have presented a rather one-sided explanation of the reasons for the relative educational failure of working class students. Thus, he argues that Hargreaves has overstated the importance of school organisation (in this case, streaming) in producing an anti-school subculture among working class (and mainly low stream) students while Willis has overstated the extent to which working class culture operating outside the school produces an anti-school subculture among working class students inside the school. [I present information on David Hargreaves’ study in the following document].

We can see the difference between Hargreaves and Willis in terms of different sequences of cause and effect. For Hargreaves, failure inside school leads to placement in a low stream which causes an anti school subculture to be produced. For Willis, an anti school subculture derives from out of school factors and this causes failure inside school. Brown has illustrated the difference neatly and is then able to say that both theories contain elements of the truth.

As we have seen , Willis‘ work was criticised on the grounds that he concentrated almost entirely on only twelve boys in non-examination classes and that the pessimistic view of working class attitudes to education which he presented was far from representative of the working class as a whole. Brown points out that sociologists have always stressed the importance of divisions within the working class (one perhaps slightly dated distinction was between the “rough” and the “respectable” working class) and that, therefore, we should expect a range of attitudes to education within the working class. Also, working class attitudes to education could be expected to vary from time to time and from place to place. Thus, for example, Willis‘ lads might well dismiss education while many unskilled manual jobs were still available as in the 1970s but by the 1980s, this was no longer the case and so at issue would be whether pupils would respond to this changed situation with a more positive recognition of the importance of education as a means of securing employment or with an even more alienated fatalism caused by the reduced availability of traditional manual employment.

In his own study, Brown distinguishes between 3 possible working class frames of reference: getting in, getting on and getting out and between Rems, Swots and Ordinary Kids. [“Rems” are essentially lower stream pupils who might be regarded as in some ways in need of “remedial” education; “swots” are higher stream pupils with good chances of educational success and “ordinary kids” are the majority of pupils who while are they not expecting sparkling academic success do aspire to some educational qualifications which will hopefully improve their employment prospects. ]

The Rems’ working class frame of reference involved getting in: that is, minimal interest in school; hoping to leave school as soon as possible, gain unskilled or semi-skilled jobs and begin the process of becoming what they see as a working class adult. Rems are more or less the equivalent of Willis “lads” although in Brown’s study the group did also contain a minority of girls. We may assume that their frame of reference derived from their particular situation in the working class community: they saw school subjects and academic qualifications as boring and irrelevant to the types of jobs that they hoped to attain; they were well aware that CSE qualifications in any case might not be very useful in the competitive job market; they also felt that they had often been poorly treated by teachers. Their views are encapsulated in some of the following statements:

“What are you gonna do with History: you’re not going to go out and be a knight or something like that, are you?” Not all this stuff like Pythagoras: it’s all stupid, that is. Be fair, go to school for 10 years to be a postman; CSEs are poxy: you are supposed to be nice in school when the teachers are treating you like the scum of the earth, that you are second class.”

The “swots” are much as expected: they are often middle class but some are working class and they are taught in the higher sets. Some of the students actually enjoy the subject matter of their subjects but also they are ambitious in terms of career and see the need to secure 10 good passes at 16+ so that they can continue smoothly to the next phase of their education. They are therefore prepared to work hard even in some subjects which do not actually interest them.

According to Brown, the main thing about ordinary kids is that they are not rems or swots. For the ordinary kids, beyond the basics, much of the school curriculum is seen as irrelevant. Basic Mathematics and English are important (but not the more theoretical aspects) as are practical subjects which might be useful for career purposes. These students are not studying for O levels but believe that reasonable CSE passes can improve their employment prospects. They believe too that such passes, although important, can be achieved without great effort and so, although they do not rebel against school, neither do they work especially hard. “The ordinary kids do what is minimally required to placate the teacher and to pass examinations, particularly when the subject is viewed as a waste of time or boring due to the way in which it is taught or due to its assumed future irrelevance,” Ordinary kids who do wish to work rather harder will be subject to considerable peer pressure not to do so. Ordinary kids will also sometimes be critical of rems: “They could have tried, if they had CSEs at least it’s something: at least they’re trying, aren’t they?”

Phillip Brown argued that by the mid1980s secondary schools could be on the brink of serious crisis brought about primarily by the growth of youth unemployment which would undermine the willingness of the majority of working class pupils [the “ordinary kids” in his sample] to work for high grade CSE qualifications as a means of securing employment for example as apprentices and junior office workers. Since such jobs were increasingly unavailable it seemed possible that more “ordinary kids” would take the more rebellious option thereby generating a crisis of serious and widespread indiscipline in British secondary schools.

I cannot do justice to Phillip Brown’s excellent sociological study in this brief summary and in particular I have not considered his critical analysis of some of the education policy initiatives introduced in the 1980s encapsulated under the heading of the New Vocationalism [although educational policy issues will eventually be covered in other documents ]He seems to have described and analysed the situations faced by many working class pupils in the 1980s with great insight and sympathy but just as Paul Willis’ conclusions appear, to some extent , to have been overtaken by events, we must wonder whether the crisis of secondary school discipline predicted by Phillip Brown, has for the time being, been avoided.

In relation to the current situation I suggest tentatively that the following points may help to explain current attitudes to education among working class pupils.

- It is noteworthy in this respect that overall levels of unemployment in the past 15 years have been far lower than in the 1980s and early 1990s.

- More pupils , including more working class pupils are remaining in education beyond the age of 16 and an increasing proportion of working class pupils are also participating in Higher Education so that, using Phillip Brown’s terminology there may well be more working class “swots” nowadays than in the mid 1980s.

- Changes in the industrial structure mean that there are relatively fewer skilled and unskilled manual jobs available for boys combined with an increased proportion of routine service jobs which may appeal less to boys than to girls although some boys will have recognised that acceptance of this kind of work does offer them a viable occupational future and will perhaps as a result be especially prepared to study for qualifications in Business Studies and IT.

- Consequently it may be that since levels of employment are relatively high and jobs for early school leavers are available in service industries, ordinary kids attitudes to education may still be reasonably optimistic except perhaps in areas where employment opportunities are more limited.

- Meanwhile there remains a minority of rebellious, mainly male pupils who are unwilling to respond positively to the recent changes in industrial structure and these pupils may find difficulty securing employment once they leave school although the majority will eventually do so.

- Nevertheless considerable attention has been given in recent years and months to a category of young people officially described as NEETS: not in education, employment or training. You may click here for a BBC item on the measurement of the numbers NEETS and their attitudes to education.

Pierre Bourdieu and the Concept of Cultural Capital

The work of Pierre Bourdieu is theoretically complex and I shall aim here only to provide a brief outline at a level appropriate for AS and A2 Level Sociology students. Theorists such as Hyman, Sugarman and Douglas aimed to provide explanations of relative working class educational failure which were based upon the concept of working class cultural deprivation and in so doing they failed to consider possible mechanisms through which education systems might be manipulated indirectly by members of the dominant economic classes to ensure that existing class structures are reproduced across the generations to ensure the continued dominance of these dominant economic classes.

The functions of formal education systems are to be analysed in a separate document but we may note here that the functions of formal educational systems and have noted that there are disputes primarily between Marxists and Functionalists surrounding the extent to which formal education systems reproduce existing class structures so that it is clear that Bourdieu’s work is relevant both to the analysis of the functions of formal education systems and to the explanation of social class differences in educational achievement.

Bourdieu has stated that he has been influenced in various ways by Marx, Weber and Durkheim but his analysis of education systems appears to be linked especially with a Marxist framework of analysis of society as a whole which will be covered elsewhere. However I am presenting below the briefest sketch of Marxist ideas in order to provide a context for this brief introductory discussion of Bourdieu’s theories. There are certainly difficult issues here that you will wish to discuss further with your teachers!

|

| In relation to Marxism we may note the following main points.

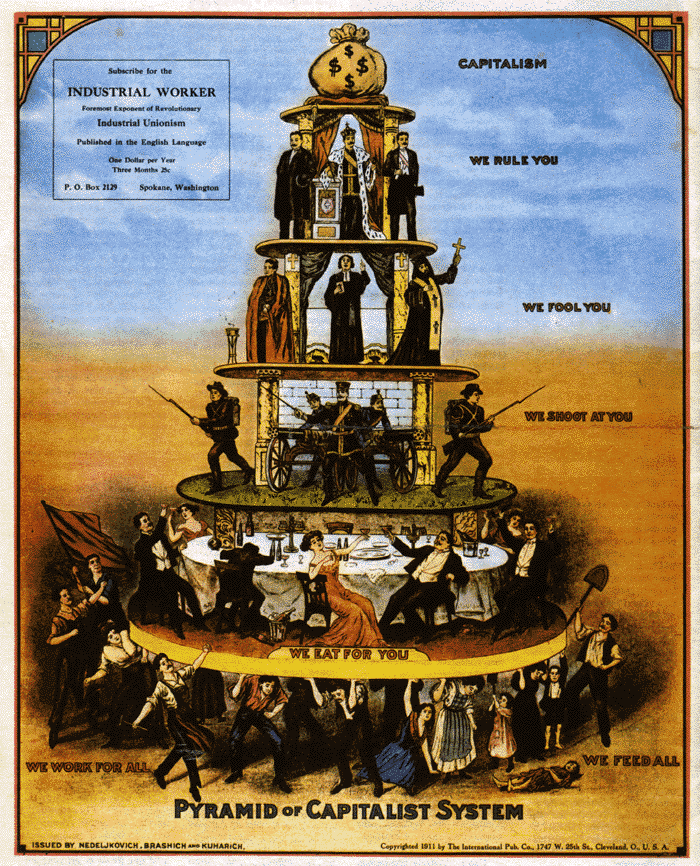

1. Marxists are critical of the capitalist system mainly because of the inequalities which it generates. 2. They argue also that the capitalist system continues to exist partly because there are important agencies of socialisation which discourage us from criticising the capitalist system and trying to change it. 3. Thus, in simple terms, the Church might tell us that “our reward will be in heaven”; the Family might tell us to concentrate on our own lives without much consideration of wider questions; the Mass Media might give a biased unsympathetic coverage of radical political criticism of the capitalist system ideas and the Education system might encourage us to accept authority without question. 4. Marxists also tend to argue that because the education system is widely perceived as fair and meritocratic, this leads us to believe that capitalist societies, although unequal, are also fair and meritocratic. The argument is that everyone has a fair chance at school and that therefore the people in the best paid jobs deserve to be there because they have more talent and have worked harder than the rest of us. 5. The Image above suggests some of the ways in which the capitalist system may be sustained. 6. However we must of course note that other sociologists reject the Marxist analysis of capitalism and argue instead that the inequalities of capitalism provide the economic incentives which encourage hard work which in turn helps to generate fairly good living standards even for the poorer members of capitalist societies. |

Bourdieu’s analysis of the causes of social class differences in educational achievement may be outlined as follows.

-

- Bourdieu’s key sociological concepts are capital, habitus and field which together are used to explain social behavior in general and patterns of educational achievement in particular.

- Individual behaviour is determined by the interaction of each individual’s capital and habitus within each particular field

- An individual’s habitus is the combination of their values, beliefs and attitudes which together form the individual’s view of the world and of their role within it. An individual’s habitus depends upon their social class position which Bourdieu emphasizes but also on their age, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and disability. However, no two individuals have an identical habitus. [ Critics of Bourdieu have argued that the concept of habitus suggests that Bourdieu has adopted an overly deterministic view of human behavior but later Bourdieusian scholars have argued that the concept of habitus can be applied more flexibly. I shall be discussing this issue in more detail in a future document on Bourdieu.]

- Fields are the various sectors of society such as the political field, the economic field, the religious field, and the education field. These fields contain a variety of institutions.

- Capital is subdivided into three main categories: cultural capital, economic capital, and social capital and within cultural capital there are divisions between objectivised cultural capital, institutional cultural capital and embodied cultural capital. Click here for a discussion of the differing forms of cultural capital.

- However, Bourdieu does also refer to symbolic capital which is in essence the social status conferred by possession of the above-mentioned types of capital and to linguistic capital which is a specific form of cultural capital.

- Bourdieu distinguishes between the cultural capital of the dominant class and the working class arguing that the classes possess different kinds of cultural capital but that one cannot argue that the cultural capital of the dominant class is superior to that of the working class. Thus, he would reject the theories of cultural deprivation based around the ideas of Hyman, Sugarman, Douglas and others.

- Bourdieu argues that because the upper class dominate society in terms of wealth and power, they can impose their culture as the dominant culture upon the rest of society and can ensure that within the education field it will be this upper-class culture which is most highly valued.

- The possession of dominant class cultural capital might imply for example a better knowledge of classical music or of "great" literature; it may imply the possession of what are considered by teachers to be higher quality linguistic skills; or it may imply a more confident presentation of self. It has proven difficult to define the concept of cultural capital precisely and to operationalize it.

- However, Alice Sullivan attempted to operationalize the concept and concluded on the basis of her research study that social class differences in parental cultural capital were passed on to their children and did influence examination results although she did note also that social class differences in examination could not be explained entirely by social class differences in cultural capital which pointed to the importance of material factors as partial determinants of educational success. ]

- Upper- and middle-class pupils will have been exposed to the dominant culture at home so that they have the cultural capital and the habitus which will facilitate their educational progress while the cultural capital and the habitus of working-class students will place them at a relative educational disadvantage

- The actual curriculum will be delivered in a linguistic style which reflects that of the dominant culture and students will be assessed mainly in terms of their possession or non- possession of this dominant culture rather than in terms of their true abilities.

- Although teachers teach in a manner that assumes that all pupils are familiar with the dominant culture, they make little attempt to impart this culture to more disadvantaged pupils thus ensuring that they remain at an educational disadvantage.

- . Working class children are likely to be relatively unsuccessful in their education but they will explain their relative lack of success in terms of their own lack of ability whereas in reality social class differences in the possession of cultural capital [ and economic and social capital], social class differences in habitus and the dominance of dominant class culture within the education field render the failure of working-class pupils almost inevitable

- Despite what, according to Bourdieu is the manifest unfairness of the education system , every attempt is made to present it as a meritocratic system in which pupils' abilities are assessed according to objective academic criteria so that this apparent fairness may be used to legitimise class inequalities in income which are presented as justified because they derive from meritocratic competition within the education system. Ironically the very fact that a relatively small proportion of subservient class children are educationally successful may be used to "prove" that the education system is indeed meritocratic.

- Bourdieu argues that possession or non-possession of the appropriate cultural capital is misrecognised as possession or non- possession of intellectual ability which means that the schools are using symbolic violence against the interests of working-class children. Thus, cultural capital can be used within the education system to transmit class privilege from parents to children to reproduce class advantage across generations

- Class privilege may also be transmitted inter-generationally via the inheritance of wealth [economic capital] and via the use of social connections [social capital] which can be used to facilitate the access of upper- and middle-class young adults to upper- and middle-class occupations.

Some Summary Criticisms of Bourdieu’s Theory

- It is argued that whereas according to Bourdieu the works of, say, Shakespeare, Beethoven or Turner are emphasized within the educational system simply because they correspond to the cultural tastes of the dominant economic class, in reality these and similar works are highlighted because they do embody objectively high aesthetic qualities not because they correspond to the cultural tastes of the dominant economic class.

- Also, insofar as such works are covered at all in school curricula this would occur in Arts and Humanities subjects and not in Mathematics and the Sciences where the impact of social class differences in cultural tastes would seem to be negligible. [However, in recent years sociologists have begun to give some attention to the notion of Science Capital and it is pointed out that scientists’ children are particularly likely to take a special interest in the Sciences and that, for example, the children of doctors are 27 times more likely than other children to become doctors themselves.]

- It is argued that Bourdieu has overstated the extent to which education systems contribute to the reproduction of existing capitalist class structures. Whereas Bourdieu argued that the operation of capitalist education systems would ensure that, with very few exceptions, upper, middle, and working class pupils were highly likely to get upper, middle, and working class jobs respectively, John Goldthorpe in particular has rejected this argument. Goldthorpe has pointed out that from the 1950s onwards increasing numbers of working class students passed GCE “O” level [ subsequently GCSEs] and A Level examination and that nowadays many working class students access Higher Education. This means, for Goldthorpe, that schools actually transmit cultural capital to working class students and increase educational opportunities for working class students to a far greater extent than is suggested by Bourdieu.

- It is argued that through his use of the concept of Habitus Bourdieu has overstated the extent to which working class students strongly entrenched attitudes and values limit their aspirations for educational and career progress. In reality many working class students are keen to make educational progress and are encouraged to do so. Also, in many cases when parents may themselves doubt their children’s educational potential, they are encouraged by teachers to believe that their children’s educational progress is possible.

The significance of social class differences in possession of economic, cultural and social capital is analysed in the recent work of Professor Stephen Ball and these practical applications of Bourdieu’s concepts are especially important for our purposes

- Stephen Ball : Class Strategies and The Education Market [2003]

In his 2003 study Stephen Ball argues that upper and middle class children are likely to be more successful in education because upper and middle class parents can deploy economic capital, cultural capital and social capital to ensure that their children have educational advantages not available even to relatively affluent working class families and certainly not available to the poor.

-

Economic Capital

- Upper and middle class parents can afford to purchase relatively expensive houses in the catchment areas of successful state schools thus helping to ensure that their children will be able to attend such schools while working class children are more likely to attend less successful schools.

- If upper and middle class children are having educational difficulties their parents can afford to purchase additional relatively expensive private tuition for their children.

- If upper and middle class parents are dissatisfied with the quality of state education in their local area they can more easily arrange for transport to state schools located further afield, or they can relocate closer to more effective schools or they can opt to have their children educated privately. Private secondary education may be unaffordable for working class parents, costing as it may around £6000-£ 8000 per year even for non boarding pupils.

- Click here for information from a recent [2013] Sutton Trust Report suggesting that "almost a third of professional parents have moved home for a good school.", Also for a more recent [2018] Sutton Trust Report which reaches similar conclusions Click here

-

Cultural Capital

- Upper and middle class parents are often relatively well educated and will almost certainly be able to help their children with homework if this proves to be necessary.

- They are likely to have the confidence to believe that any educational difficulties experienced by their children can be resolved through discussion with teachers and are unlikely to assume that such difficulties are evidence of their children’s’ limited academic abilities.

- They are more likely than working class parents to be able to interpret the fairly detailed statistics on school performance which are nowadays published and therefore better able to make an informed choice of schools for their children.

- If popular schools are oversubscribed upper and middle class parents may be able to create favourable impressions which help to secure entry for their children to over- subscribed schools.

- They may socialise their children to present themselves sympathetically in the eyes of mainly middle class teachers.

- They may provide leisure activities for their children [such as Music, Drama and additional sporting activities] which enable the children to present themselves more effectively, for example in University interviews.

-

Social Capital

- Upper and middle class parents may be in social contact with other upper and middle class parents who can help them to evaluate the relative effectiveness of different schools prior to school choice.

- They may know of particularly effective private tutors.

- They may be able to arrange particularly useful work experiences or contacts with personal friends who are university lectures which will enable their children to prepare far more effectively for university entrance.

Using these ideas enables us to clarify more clearly the distinction between theories based upon cultural deprivation and theories based upon cultural difference. In theories based upon cultural deprivation, working class parents and their children have been presented as “lacking in ambition, fatalistic, unwilling to plan for the future and with a strong present time orientation” all of which contribute to relative educational failure. It is possible that ongoing economic hardship can help to generate such attitudes in some families but many sociologists argue that the vast majority of working class parents are ambitious for their children but that they cannot translate their ambition into effective help because of their limited economic, cultural and social capital. I hope that the following activity will clarify further the distinction between theories based upon cultural deprivation and theories based upon cultural difference.

| Activity: Cultural Deprivation and Cultural Difference

1. Briefly explain the terms economic capital, cultural capital and social capital. 2. Would you agree that, broadly speaking middle class families are likely to have more “cultural capital” than working class families? Give reasons for your answer. 3. How might social class differences in the possession of cultural capital help to explain social class differences in educational achievement? |

Part 4: Sociological Explanations of Social Class Differences in Educational Achievement: Material Economic Differences - Click Here