Voting Behaviour in the UK : Document Two : From the 1970s to the General Elections of 1992 and 1997

[As of August 2017 I found that some links in this document had been broken but as of September 2017 they have all [hopefully!] been mended ]

|

My Voting Behaviour documents have now been restructured, updated and revised. The original version of the first document has been divided into two sections with little further revision but the original document on the 1970s to the 1990s has been divided into two sections and revised quite significantly in an effort to clarify the differences between the various models of voting behaviour developed from the 1970s to the 1990s. The third document on the General Elections of 1997, 2001 and 2005 has been modified slightly and I have now also written a document on the 2010 General Election . Finally I have also recently added two pages of links on the 2015 and 2017 General Elections respectively. Thus the new structure is as follows:

|

- Voting Behaviour in the UK : Document Two : From the 1970s to the General Elections of 1992 and 1997

Page last edited :

This document has been and restructured during the Summer and Autumn of 2010. It is now divided into two main sections on [1] Models of Voting Behaviour and [2] the General Elections of 1992 and 1997 respectively .The first section on Models of Voting Behaviour contains a little additional material not provided in the original version of the document but I have made no changes to the second section on the General Elections of 1992 and 1997.

- Section One :Models of Voting Behaviour

I hope that the following Titles within this document will enable students to navigate easily to information on each specific model of voting behaviour.

- Introduction

- The Party Identification Model

- The Decline of Party Identification or Partisan Dealignment

- Class Dealignment: Measurement and Causes

- The Radical Model of Voting Behaviour

- The Issue Voting Model of Voting Behaviour

- The Ideological Model of Voting Behaviour

- The Dominant Ideology Model of Voting Behaviour

- Key Political Events

- The Voting Context Model of Voting Behaviour

- Section Two: The General Elections of 1992 and 1997

- Introduction

- The General Election of 1992

- The General Election of 1997

- Assignment: Comparing the General Elections of 1992 and 1997

- Section One: Models of Voting Behaviour

- Introduction

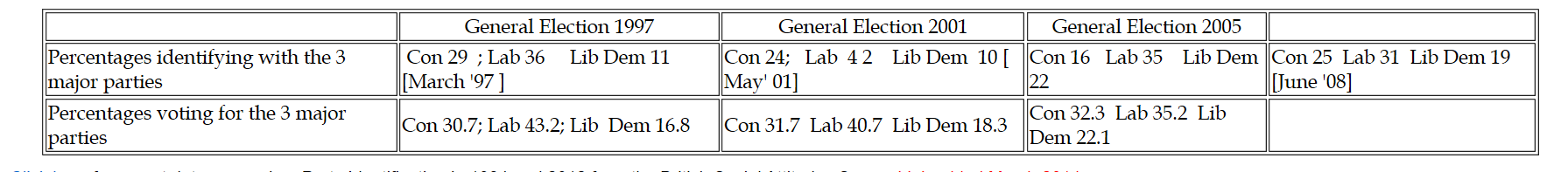

The analysis of voting behaviour is known also as "psephology" deriving from the Greek "psephos" [a pebble] with which the ancient Athenians indicated their voting decisions. Psephologists in the UK distinguish between the period of 1945-1970 which they characterise as the era of electoral stability, two party dominance, party identification and class alignment and the period from 1970 to the present day which is described as the era of declining party identification/partisan dealignment and class dealignment although there are also important arguments as to whether the general elections of 1997 and 2001 ushered in a realignment of UK voting behaviour.

As patterns of voting behaviour became increasingly complex psephologists developed various models of voting behaviour often involving advanced statistical method to explain voting trends and by 1990 W. I. Miller suggested that it was useful to distinguish between 6 main models of voting behaviour, a procedure which is still followed in several text books and will be followed also in this document.

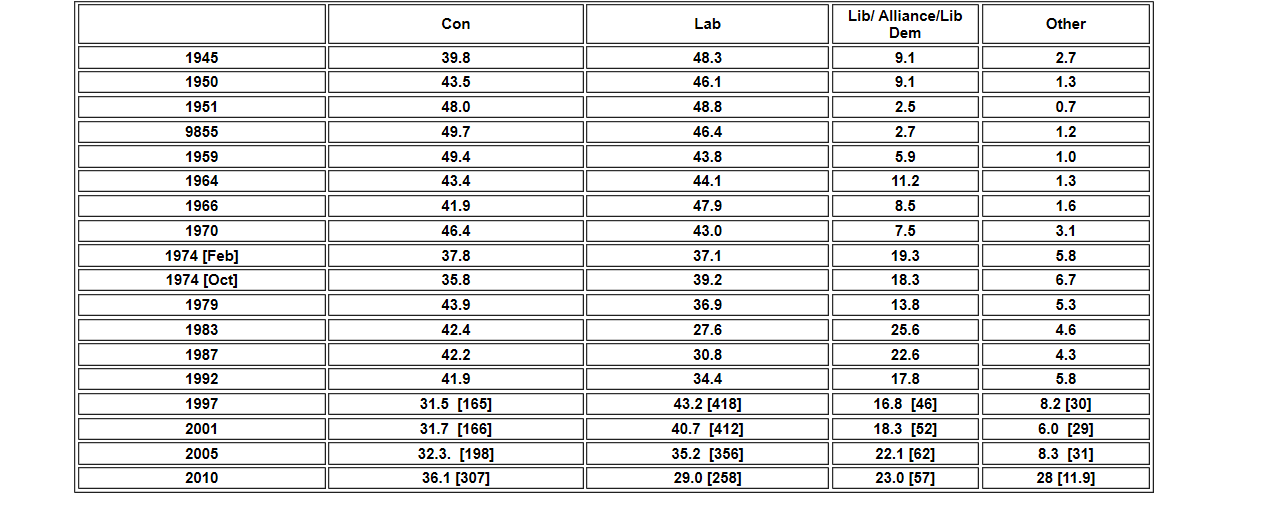

Let us begin with a broad consideration of the period of 1945-1970 which has been described as a period of relative electoral stability dominated by the two major political parties: the Conservative Party and the Labour Party. Thus between 1945-1970 the Conservative and Labour Parties regularly gained approximately 90% of the votes cast in general elections which under the conditions of the "first past the post" electoral system translated into approximately 98% of the parliamentary seats while the Ulster Unionist Party [UUP] gained a further 10-12 seats and could be relied upon to regularly support the Conservative Party in parliament. Neither the Liberal Party nor the Nationalist parties offered any real challenge to this 2 Party dominance. Further aspects of electoral stability were that opinion poll fluctuations and by election swings were relatively narrow and surveys indicated that relatively few voters switched their party allegiance between general elections although more switched between voting and non- voting. The relative stability of opinion polls suggested that most voters were influenced far less by short term political issues than by long term social structural factors to be discussed below and variations in general election results could be said to be determined by the relatively small percentages of so-called floating voters who did switch party allegiance between general elections.

Election Results: Percentages of the Popular Vote [and seats won in most recent General Elections]

- The Party Identification Model

The Party Identification Model has been described at length in the previous document. In summary this model contains the following elements.

- Psephologists demonstrated that from the 1950s to the early 1970s voting behaviour was clearly correlated with a range of social variables including social class, age, gender, region, religion and "race" or ethnicity and that social class was the most significant influence on voting behaviour which enabled P.G.J. Pulzer to write in Political Representation and Election (1967) that "Class is the basis of British party policies: all else is embellishment and detail", a conclusion which was endorsed fully by David Butler and Donald Stokes in their famous study "Political Change in Britain [1969: second edition 1974].

- The vast majority of British voters [approximately 90% of respondents in Butler and Stokes' surveys] stated that they did identify with either the Conservative Party, the Labour Party or, to a lesser extent the Liberal Party and the respondents' party identifications usually remained relatively stable over the course of several elections and often throughout voters' lives sometimes hardening with age.

- Their party identification was correlated strongly with their actual voting behaviour such that, for example, in the Local Elections of 1963 85% of Conservative identifiers, 95% of Labour identifiers and 88% of Liberal identifiers voted in accordance with their stated party identification.

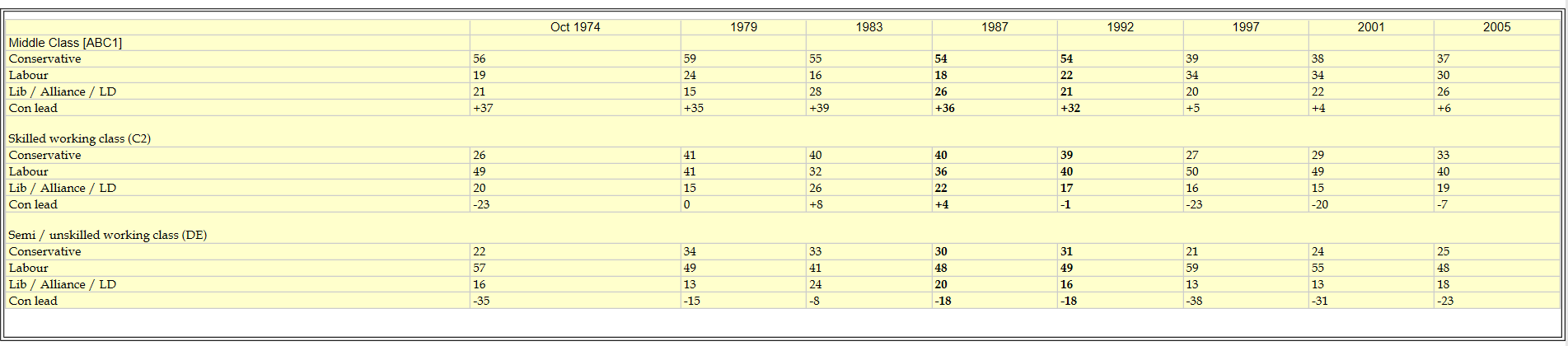

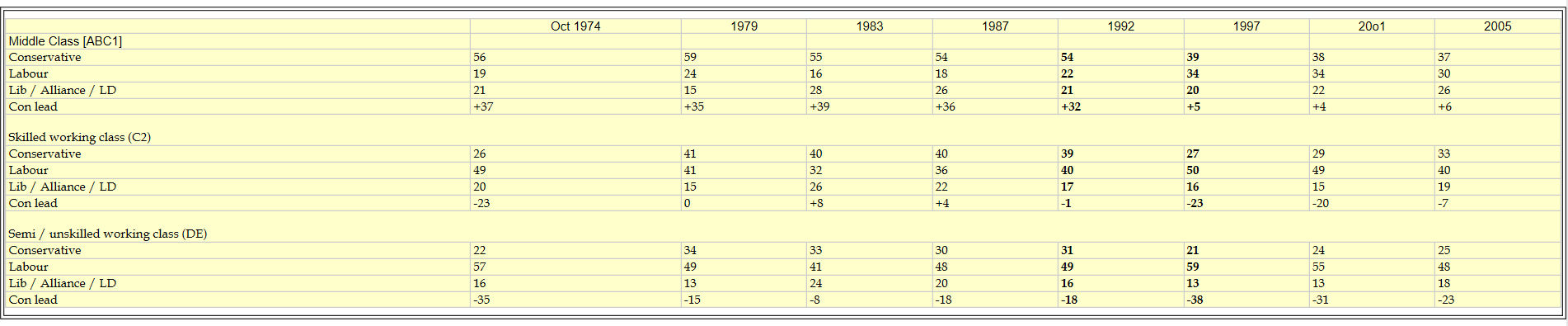

- Statistics illustrated that there was a strong correlation between voters' objective social grade position [as measured by occupation as in the schema developed for use in the National Readership Survey in which individuals are assigned to "social grades" A, B, Cl, C2, D and E defined as follows: A=Higher professional, managerial and administrative; B =Intermediate professional, managerial and administrative; C1 =Supervisory, clerical and other non-manual; C2=Skilled manual; D=Semi-skilled and unskilled manual; E= Residual including casual workers and people dependent wholly on state benefits ] and their actual voting behaviour from 1945 to 1970 . You may click here and here for further information on this schema and for trends indicating the relative decline and increase in the sizes of the middle and working classes respectively in the last 50 years or so. Social grade as measured via this schema is not the same as "social class" but it is used as a proxy for social class many studies of voting behaviourin s

- The link between voting behaviour and social class was at its strongest in the General Elections of 1950 and 1951 when approx. 2/3 of working class voters voted Labour and 1/3 Tory, while approx 3/4 of the middle class voted Tory and 1/5 Labour. Class voting remained fairly high throughout the 1960s while support for the Liberals was very low and fairly evenly distributed across the social classes, although with a slight middle class bias.

But why did so many voters vote in accordance with their social class position between 1945-1970?

- Butler and Stokes argued that most voters had only limited knowledge and understanding of key political issues of the early 1960s such as the state of the UK economy or the desirability of otherwise of UK entry into the EEC [as it then was; they could only rarely describe in any detail the policy differences between the political parties; and their political opinions were often ideologically inconsistent in the sense that they could only rarely be combined into composite ideological positions which were recognisably "left wing" or "right wing" or "centrist."

- Therefore for most but not all voters the voting decision could not be explained as an individual response to perceived differences in party policies. Instead voting decisions could be better explained via the influences of long term social structural factors: it is in this sense that the Party Identification model came to be described as a sociological model of voting behaviour [as distinct from the more individualistic models of voting behaviour which were developed from the 1970s onwards. However Butler and Stokes did not deny totally the influences on voting behaviour of short term and medium issues, policies and events but these were considered to be much less influential than long term social structural factors.

- Butler and Stokes argued that voters were heavily influenced by long term processes of political socialisation operative especially in the family but also in the work place and the wider community which presented them with generalised broad images of the political parties. Thus Labour might be presented as the party of the disadvantaged, of the trade unions, of the working class of nationalisation or of the welfare state while the Conservative Party might be presented as the party of private enterprise, of private property and the nation as a whole.

- There were also, obviously important social class differences in these processes of political socialisation n which working class people and middle class people to identify especially with the Labour Party and the Conservative Party respectively and to vote accordingly. [ Within these class differentiated socialisation processes members of each social class would be provided both with positive images of "their party" and negative images of opposing parties].

- Given their relatively large numbers if all working class voters had voted Labour between 1945 and 1970 Labour would have won every single general election. However a substantial minority of working class voters voted Tory, and also a smaller, but still substantial minority of middle class voters voted Labour, even at the high point of class voting in the General Elections of 1950 and 1951. These cross-class voters, given their relatively small numbers, were described as "deviant" voters and various explanations were suggested to explain their deviant voting patterns. [See document one.]

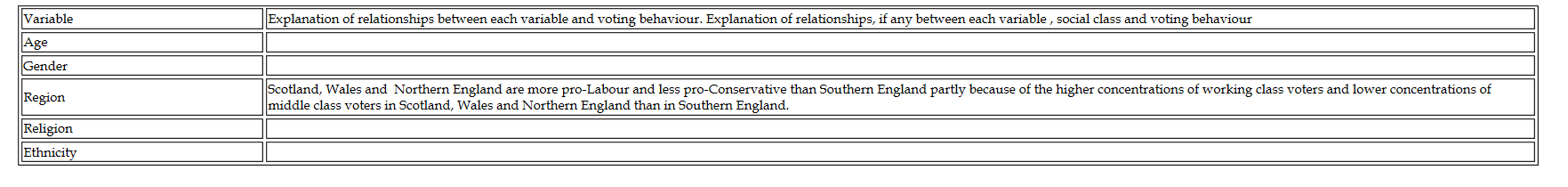

- Although we can agree with the already mentioned statement from P.G.J. Pulzer in Political Representation and Election (1967) that in relation to the period between 1945 and 1970 "Class is the basis of British party policies: all else is embellishment and detail", it is also necessary to investigate the effects of other social factors [ age, gender, region, religion and ethnicity] on voting behaviour in the period 1945-1970. In several cases we shall find important connections between these variables and the more significant variable social class variable and these interconnections provide further support for P.G.J. Pulzer's statement. For further information on these non-class influences on voting behaviour after which you may like to complete the table.

The Party Identification Model of Voting Behaviour: A Summary of a Summary!

- The Party identification suggests that voters decisions are influenced much more by social structural variables [and especially by their social class position but also by their age, gender, region, religion and ethnicity] than by short term issues, policies and events .

- Differing social class positions result in class differences in political socialisation processes operating in the family , the work place and the wider community.

- Class differences in political socialisaton processes result in the transmission of differing broad party images which encourage working class and middle class people to identify mainly with the Labour Party or the Conservative Party respectively.

- Most voters vote in accordance with their party identification.

- That is: for most voters social class differences result in social class differences in social class differences in political socialisation, social class differences in party images, social class differences in party identification and social class differences in voting behaviour.

- The Decline of Party Identification or Partisan Dealignment :

Psephologists have emphasised the extent to which Party Identification [which was so central to the explanation of voting behaviour in Butler and Stokes' Party Identification Model] declined significantly especially in the 1970s. It is generally agreed that since then overall party identification has changed little although there has been further long term decline in the extent of strong party identification.

Click here for Ipsos Mori Data on UK General Election 1974-2010 and on the General Elections of 2015 and 2017

As we consider the possible causes of the decline in party identification or partisan dealignment we may distinguish between longer term broadly sociological or social structural influences and more political [ and often but not always more short-term] influences although it is difficult to determine precisely where the boundary between Sociology and Politics actually lies . Several possible reasons have been suggested for the decline of party identification and in each case I have classified these reasons as either broadly sociological [S] or broadly political [P] or as a mixture of the two. [SP]

- Changes in the nature of individual social classes and in the class structure as a whole could result in partisan dealignment .

- For example increasing working class affluence, the decline of traditional working class communities, the growth of the "new working class" and the increased importance of sectoral cleavages within the working class could all in principle result in declining party identification with the Labour Party. [S]

- Traditional processes of political socialisation which encouraged working and middle class people to identify with the Labour and Conservative Parties respectively have weakened thereby weakening traditional allegiances with these political parties. [S]

- Improved average education levels may enable more people to appreciate the complexity of political arguments and to recognise that no single political party has the "right answers" to political problems. Although it is also true for some people that increased education strengthens rather than weakens their party identification they may be in a minority. [SP]

- Since the 1950s political issues have been covered in greater detail in the mass media and as individuals access serious TV and radio discussions between major spokespersons of the political parties and/or careful media analyses of party political programmes they may increasingly come to see merit in different sides of political questions and therefore to identify less with one particular party political viewpoint. This seems a generally plausible argument although it may also be argued that some listeners/watchers of serious political programmes may be especially likely to be strong party identifiers who will not easily discard their long term party identification although the party identification of other watchers/listeners may well weaken. [P]

- Alternatively peoples' identification with any one particular political party may be much weakened by more strident campaigns in the popular press against what would otherwise have been their preferred political party. [SP]

- People may interpret the performances of both major parties in government as poor leading to declining identification with both major political parties as occurred for example in the late 1960s and 1970s due to the perceived inabilities of both Labour and Conservative governments to manage the economy effectively. [P]

- By the 1970s it was possible that increasing affluence led some voters to concern themselves increasingly with so-called post-materialist issues relating to environment, quality of life , civil liberties, nuclear disarmament and "Third World" development which they believed were not being addressed seriously by the major political parties all of which resulted in declining party identification [and in some cases increased pressure group membership] among such individuals. [P]

- In the original formulation of the party identification model by Butler and Stokes it was suggested that party identification had a degree of permanence as a result of long term processes of political socialisation which caused working class and middle class voters to identify primarily with the Labour Party or the Conservative Party respectively and that individual issues, policies and political leaders had little influence on voting behaviour. However it has increasingly been argued that party identification also has an important more transitory component such that party identification could be influenced also by changes in party leadership, changes in ideology, changes in image and changes in policy. Thus, for example, party identification with Labour may have declined in the late 1960s and 1970s due to disaffection among previous party identifiers with core Labour Party principles of public ownership, increased welfare spending and support for the trades union movement. Similarly, the 1992 ERM crisis could have reduced identification with the Conservative Party while disillusion with the New Labour project could have reduced identification with the Labour Party especially by the time of the 2005 General Election. This latter point suggests that the Party Identification Model may to some extent overlap with the Issue Voting Model to be considered later. [SP]

It is likely that the above factors causing individual partisan dealignment are likely also to lead to class dealignment : that is: to a weakening of the relationships between social class and voting behaviour: for example increased affluence within the working class may cause many working class voters to identify less with the Labour Party and to cease voting Labour and working class voters might also identify less with the Labour Party as a result of unpopular changes in Labour Party policy which also discourages them from voting Labour and leads, therefore to class dealignment. However it may be possible that in some cases partisan dealignment may not result in class dealignment for example as when working class voters' identification with Labour declines but they continue to vote Labour because they identify even less with the other political parties.

Let us now investigate the phenomenon class dealignment in more detail.

- Class Dealignment: Measurement Difficulties and Causes. [It may be that familiarity with some of these technicalities is not required in the new Government Politics Specifications. Check with your teachers!]

- Class dealignment occurs when working class voters become decreasingly likely to vote for their "natural class party": i.e. for the Labour Party and /or when middle class voters reduce their support for their "natural class party": i.e. for the Conservative Party.

- However the actual measurement of the extent of class dealignment has presented several problems.

- There are major controversies surrounding the concept of social class and the analysis of the UK class structure. In studies of voting behaviour psephologists have traditionally used the AB, C1 , C2, DE social grade schema to analyse relationships between social class/social grade and voting behaviour and it is generally agreed that in the last 40 years there have been significant changes in the shape of the UK class structure involving the relative growth of non-manual [or "middle class"] employment and the relative decline of manual [or "working class"] employment which in principle could be expected to harm the electoral prospects of the Labour Party.

- However Heath Curtice and Jowell argued in their study "How Britain Votes [1985]that the traditionally used social grade scheme [the AB, C1, C2, DE scheme] provided inaccurate measures of class position and that it should therefore be replaced by a more theoretically sophisticated social class schema involving the allocation of individuals into a new five class schema containing the salariat, routine non-manual workers, the petty bourgeoisie [including self employed manual workers], foremen and technicians and the working class . In this schema classes are defined so as to take account of differences in authority and autonomy at work as well as differences in income and the authors' data suggest that these variables have a considerable impact on voting behaviour. Clearly some complex technical details are involved here but the authors point out that, for example once foremen are defined out of the working class the remaining skilled manual workers are more likely to vote Labour than semi-skilled and unskilled workers which is the reverse of the conclusion derived from the AB, C1, C2, DE schema. Thus the measured extent of class dealignment varies according to the social class schema which is used to measure it.

- Furthermore it is important to distinguish also between trends in absolute class voting and trends in relative class voting. [October 2011: I have now included a numerical example showing the calculation of Absolute Class Voting, the Alford Index and the Odds Ratio.]

- The extent of class dealignment was first measured in terms of the decline in absolute class voting . Absolute Class voting is a measure of the proportion of all voters who vote for their natural class party: it is the total number middle class Conservative voters and working class Labour voters as a percentage of the total votes cast. The first attempts to measure relative class voting made use of the Alford Index: the Labour Alford Index is the percentage of working class voters voting Labour minus the percentage of middle class voters voting Labour; similarly the Conservative Alford Index is the percentage of middle class voters voting Conservative minusthe percentage of working class voters voting Conservative.

- However the psephologists Heath, Curtice and Jowell also suggested in their study "How Britain Votes [1985] that class voting should be measured in relative terms but that relative class voting could be measured more effectively by Odds ratios rather than by means of the Alford Index. A range of different odds ratios may be calculated which measure the relative likelihoods of members of different social classes voting for different parties The Odds Ratio comparing middle class and working class likelihoods of voting Conservative rather than Labour is calculated as follows: it is [the percentage of middle class voters voting Conservative divided by the percentage of middle class voters voting Labour ] divided by [the percentage of working class voting Conservative divided by the percentage of working class voters voting Labour]

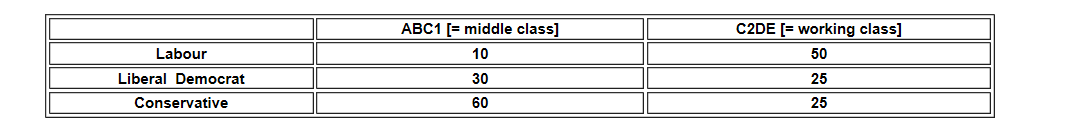

- The calculations of the different measures of class voting are illustrated in the following hypothetical numerical example.

- Absolute class voting is a measure of the proportion of all voters who vote for their natural class party. 60% of Middle class voters have voted Conservative and 50% of working class voters have voted Labour but we cannot calculate the precise extent of absolute class voting from these data because we do not know the relative sizes of the middle and working classes. However if both the middle and working classes represented exactly 50% of the voters then we could say that Absolute class voting was 55% of all voting. Notice also that the statistic for absolute class voting as a percentage of the electorate would be lower because of the effects of abstention and we should also need to calculate the impact of social class differences in abstention.

- The Labour Alford Index is the %of the working class voters voting Labour minus the % of the middle class voters voting Labour [= 50% minus 10% =40%.] The Conservative Alford Index is the % of middle class voters voting Conservative minus the % of working class voters voting Conservative [ 60% minus 25%= 35%]

- The Odds Ratio comparing middle class and working class likelihoods of voting Conservative rather than Labour is calculated as follows: it is [the percentage of middle class voters voting Conservative divided by the percentage of middle class voters voting Labour ] divided by [the percentage of working class voting Conservative divided by the percentage of working class voters voting Labour]. Thus it is: 60/10 divided by 25/50 =12. Essentially middle class voters are 6 times more likely to vote Conservative rather than Labour and working class voters are half as likely to vote Conservative rather than Labour giving an Odds ratio of 12.

- According to Heath, Curtice and Jowell when the new class schema is adopted and class voting is measured in relative terms using trends in Odds Ratios over time there was no evidence of class dealignment after all, although the authors did agree that the long term decline in the size of the working class had harmed Labour considerably.

- These conclusions in relation to class dealignment for a time generated considerable controversy in the psephological community. However it is now widely agreed that these controversies have subsided because in the General Elections of the 1990s there was evidence of class dealignment however it was measured. Furthermore class dealignment increased still more in the General Elections of 2001, 2005 and 2010.

- I have had some difficulty finding a link to data on trends in class dealignment as measured by the methods mentioned above but you may now click here and visit slide 31 of a lecture presentation by S. Fisher which has a diagram from Political Choice in Britain 2004. The Consistency Index referred to in the diagram is [the percentage of working class voters voting Labour minus the percentage of middle class voters voting Labour] plus [the percentage of middle class voters voting Conservative minus the percentage of working class voters voting Conservative.] This means that the Consistency Index = the Labour Alford Index plus the Conservative Alford Index. If required you may also consult Political Choice in Britain [ a very detailed complex study by H. Clarke, D. Sanders, M. Stewart and P. Whiteley 2004], Elections and Voters in Britain [David Denver : Second Edition 2007] and Sociology Themes and Perspectives [Haralambos and Holborn] for further discussion.

- If we remember that at the high point of class voting in the General Election 1951 [when support for minor parties was very low] approximately 80% of middle class voters voted Conservative while approximately 20% voted Labour and approximately 65% of working class voters voted Labour while approximately 35% voted Conservative you may Click here for Ipsos Mori Data on UK General Election 1974-2010 and on the General Elections of 2015 and 2017

I shall have occasion to repeat this link at intervals later in this document. ]

- You may now click here for an Assignment on Social Class and Voting Behaviour 1992 -2019

- Class Dealignment : Causes As is the case with partisan dealignment we may also here between sociological and political explanations of class dealignment. consider some sociological explanations of class dealignment.

- Working class dealignment could in principle be caused by changes in political attitudes which in turn were caused by sociological changes in the nature of the working class deriving from embourgeoisement and/or the growth of the new working class and/or increasing sectoral cleavages most notably between public sector and private sector workers and/or between consumers of private health care, education and transport consumers and consumers of publicly provided health care, education and transport and/or the growth of a "new working class" different in several respects from the "old working class."

- From the 1950s onwards it was increasingly suggested that the more affluent sections of the working class were experiencing a process of Embourgeoisement. That is to say, these manual workers were becoming middle class. Their work was now less physically demanding; they were regularly consulted by management; they were better paid than many clerical workers; and it was claimed that consequently they did not see themselves as working class and partly as a result of this, were unlikely to vote Labour which helped to explain the three successive defeats for Labour in the General Elections of 1951, 1955 and 1959. If this theory was correct, the boundary between the middle class and the working class was becoming very blurred especially if some proletarianisation of the clerical worker was also occurring.

However, the theory of Embourgeoisement was heavily criticised by Goldthorpe, Lockwood, Bechhofer and Platt in the so-called "Affluent Worker" studies of the late 1960s in which they aimed to compare the class positions of affluent factory workers, clerical workers and members of the traditional working class. I shall not consider the details of the study here but in summary, Goldthorpe and Co. claimed to have uncovered not a process of Embourgeoisement but the emergence of a "new working class" whose work experience, life styles, attitudes and values, although different from those of the traditional working class, were ,nevertheless, still recognisably working class. They argued also that a process of "normative convergence" between the "new working class" and the clerical workers was underway as clerical workers also increasingly joined trade unions attempting to halt the relative decline in their living standards

The authors found also that in the late 50s and early 60s, affluent manual workers were still highly likely to support Labour as shown by the fact that 80% of their sample had voted Labour in the 1959 General Election. However, the Goldthorpe Lockwood study also indicated that this affluent working class support for Labour was conditional, instrumental and potentially volatile such that under different political circumstances, the affluent manual workers in the Goldthorpe Lockwood study could easily imagine themselves voting Conservative . Working class support for Labour did fall considerably in the 1970 General Election won by the Conservative Party but Labour recovered to some extent in the two General Elections of 1974, both of which it won narrowly.

The Conservatives under Mrs. Thatcher won the General Election of 1979 which resulted in another significant decline in working class support for Labour such that by 1979 only 41% of C2 and 49% of DE voters were voting Labour. In 1983 Labour again lost working class support not to the Conservatives but to the Lib/SDP Alliance but from1983 onwards working class support for the Labour Party gradually began to increase again. Nevertheless by the late 1980s, it was again argued by some that the Embourgeoisement process was underway as the living standards of manual workers in secure employment did improve significantly and more and more of them bought their own houses , bought shares in privatised industries and were more likely to vote Conservative now than they had been in the 1960s, thus contributing importantly to Conservative General Election victories of 1979, 1983, 1987 and 1992. However social class inequalities actually increased in the 1980s and early 1990s again discrediting the idea that affluent sections of the working class were now experiencing embourgeoisement but the increased affluence of many working class voters may nevertheless have encouraged more of them to vote Conservative even if they were still "objectively working class."

- Class dealignment might also be explained in terms of the so-called radical model of voting behaviour which was developed by P.Dunleavy and Christopher Husbands in their study "British Democracy at the Crossroads" [1985] . The radical model of voting behaviour which departed in several respects from the traditional Party Identification Model but also called into question some of the conclusions of the Issue Voting Model[ to be discussed below]. According to Dunleavy and Husbands class dealignment occurred because of the growth of sectoral cleavages within both the working class and the middle class as between public sector and private sector workers and between consumers of publicly and privately provided housing, health care, education and transport. Public sector workers and consumers of publicly provided services are more likely to Labour because they perceive Labour as the party most likely to improve public sector pay and conditions and to improve public services while private sector workers and consumers of privately services may be more likely to vote Conservative because they oppose the higher levels of taxation necessary to defend public service employment and the expansion of public services which they do not use. Thus the theory helps to explain why middle class public sector employees and/or consumers of publicly provided services are disposed to vote Labour and working class private sector employees and/or consumers of privately provided services are more likely to vote Conservative. [Also in their radical model Dunleavy and Husbands claim that governments may use their own policies to improve their own electoral prospects [as when the Conservatives embarked on a programme of council house sales; that the mass media help to spread a dominant class ideology whose widespread acceptance means that the voters' decisions are not as "rational" as is sometimes implied in models of issue voting and that the apparent correlation between voters policy preferences and their voting behaviour may arise because they have adjusted their stated policy preferences to conform to their voting decisions which have actually been determined by other factors. They argue also that the power of governments to determine the timing of the general election gave the Conservatives a significant advantage in 1983 . However it did not help the Conservatives in 1997 and it may be that it is unlikely to help Labour in 2010.

- Later in this document we shall consider the dominant ideology model which focuses entirely on ways in which the mass media disseminate a dominant class ideology . As we now see Dunleavy and Husbands' radical model incorporates the dominant ideology but also includes other important elements.

- Class dealignment has also been explained by Ivor Crewe in terms of differences between the old and the new working class noting that in the General Elections of 1987 and 1992 working class people living in the North or renting council accommodation or who were trade union members or who worked in the public sector[= "the old working class" ] were more likely to vote Labour than were working class people living in the South or buying/owning their own accommodation or who were not members of trade unions or who worked in the private sector [="the new working class"]. The predicted future growth of the new working class and decline of the old working class could be expected to harm Labour's electoral prospects or so it was thought in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Crewe noted also that there appeared to be significant divisions within the middle class: middle class voters who were university educated and worked in the public sector were less likely middle class voters working in the private sector to vote Conservative and more likely to vote for the Alliance Parties and for the Labour Party. Perhaps it would be those middle class voters who by 1997 would be especially attracted to New Labour?

- We may adapt the above analyses to distinguish between Labour's core working class support and working class voters who occupy cross class locations. If Labour's core voters are those who live in the North and in council housing and work in the public sector and are members of trade unions it is clear that an increasing proportion of working class people do not fall into all of these categories so that they may be said to occupy cross class locations and as a result they may be less like than the core voters to vote Labour all of which increases the probability of class dealignment.

- Increasing numbers of families may be seen as mixed class families where for example male partners are skilled manual workers and female partners are clerical workers. One or other of the partners may be fairly likely to vote against their "natural class party" because of their exposure to competing political messages.

- Class Dealignment: Individualistic, Political Explanations Based On the Issue Voting Model and Criticisms of the Issue Voting Model

Click Here and Here and scroll down for Ipsos Mori Political Monitor and Issue Index at the time of the 2010 General Election and for more recent editions Click here for long term trends in the relative importance of different political issues.

Click here and scroll down for Ipsos Mori April 2015 Issues Index and Election Special. The latter has good information on Best Party on Key Issues at the time of 2015 General Election and previous General Elections

- The 1970s trends in partisan and class dealignment were explained partly in terms of the sociological trends [which have been discussed above] but also in terms of more individualistic models of voting behaviour known variously as rational voting, judgmental voting consumer voting or issue voting models in which it was argued that voters' decisions were now less influenced by social background factors [and especially by social class] and more influenced by individual voters' own assessments of different political parties' policies on issues which they considered to be salient.

- Although Butler and Stokes argued that party policy differences on specific political issues exercised only limited influence on voting behaviour they did nevertheless specify that if policy differences on political issues were to influence at least some effect on voting behaviour voters must be aware of particular issues, voters must have attitudes or opinions on particular issues, voters must detect differences between parties on particular issues and voters must actually convert their preference into actually voting for the party whose views on particular issues approximate to their own.

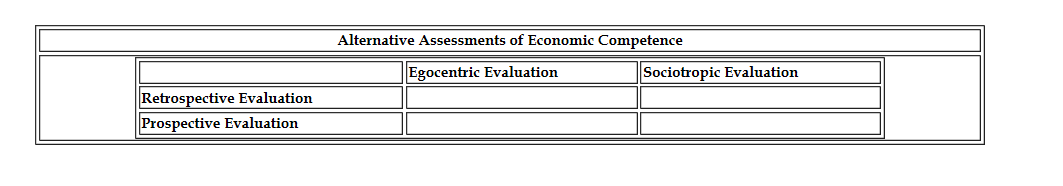

- Furthermore Butler and Stokes were among the first psephologists to distinguish between Spatial Issues and Valence Issues. Spatial issues are those on which political parties adopt different political positions: [for or against privatisation; for or against increased taxation; for or against increased government spending; for or against greater economic equality; for or against industrial relations legislation sympathetic to the trade unions and so on] whereas valence issues are those on which there is a general consensus among political parties and voters in that for example all political parties and all voters are in favour of increased economic efficiency , improved living standards, better health care and reduced crime and on these issues voters are assumed to choose between the political parties on the basis of their assessments of the likely competence of the political parties to achieve these objectives.

- Especially important are the voters assessments of the economic competence of the political parties but it is also possible that even if voters approve of a particular party's policies on particular issues they may still doubt the competence of that party to implement its stated policies effectively thereby undermining that party's electoral prospects. It has been argued also that the increased importance of valence issues has increased the importance of political leadership as a determinant of voting behaviour as voters' perceptions of overall party political competence are nowadays said to depend heavily of their relative perceptions of the competence of different party leaders.

In the era of strong party identification prior to the 1970s it was usually argued that leadership effects on voting behaviour were much weaker than the effects of party identification. There were very strong correlations between party identification and leadership preferences and where there was no such correlation it was clear that voting decisions were influenced more strongly by voters' party identification than by their leadership preferences. Thus, for example Butler and Stokes calculated that in the 1960s Labour identifiers who preferred the Conservative leader nevertheless voted Labour rather than Conservative in the ratio 2:1 and that Conservative identifiers who preferred the Labour leader still voted Conservative in the ratio 3:1.

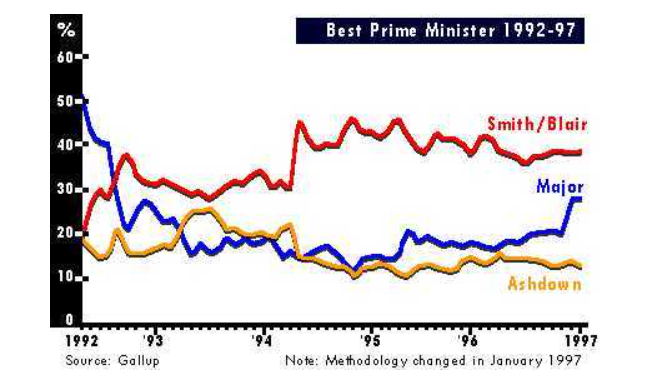

In general elections between 1964 and 2005 it is clear that the party with the most popular leader usually won the general election although there were exceptions as when the Conservatives won in 1970 although Labour leader Harold Wilson was more popular than Ted Heath and in 1979 when Labour leader James Callaghan was more popular than Margaret Thatcher.

It has been argued more recently that in the era of declining party identification and increasing mass media focus on the political leaders that political leadership is an increasingly important influence on voting behaviour. This may arise especially if party policy differences on spatial salient issues are relatively small because in these circumstances perceptions of overall governing competence to deliver on valence issues [such as improved living standards, better health care and reduced crime] are likely to be more significant determinants of voting behaviour and it is the perceived abilities [or otherwise] of the party leaders [and other significant members of the leadership team] which are crucial to the creation of an image of governing competence.

Using this line of argument voters relative preference for John Major over Neil Kinnock in 1992 helped to improve the Conservatives' overall ratings for economic competence and thereby helped them to win the 1992 General Election while voters' preferences for Tony Blair over John Major [1997], William Hague [2001 ] and Michael Howard [2205] are considered by many to have been important influences on the General Election results of 1997, 29001 and 2005 although it has also been argued that Blair's declining popularity did cost Labour votes in 2005 although he was at least still more popular than Michael Howard. Nevertheless some controversy still exists: some famous analysts such as Ivor Crewe argued for example that in 2001 the Conservatives lost more because William Hague was unable to offset the unpopular policies and image of the Conservative Party than because he actually added to Conservative unpopularity.

Also, if it should be the case that actual differences in party policies on specific issues are small this will obviously increase the significance of valence issues as voters are more likely to vote on the basis of their assessments of overall governing competence. For this reason valence issues may have been especially significant in the General Elections of 1997 , 2001 and perhaps to a lesser extent in 2005.

- Issue voting models focused initially on the importance of spatial issues rather than valence issues. Thus it was noted first of all that there was declining support among the electorate and also among regular Labour voters for core Labour party policies such as close links with the trades unions, nationalisation and high levels of welfare state spending and then argued that the victory of the Conservatives in the 1979 General Election could be explained at least partly because the Conservatives were preferred to Labour on several of the most salient issues of the campaign.

- However we should not overstate the importance of spatial issues as influences on voting behaviour because even in the 1980s important criticisms had been made of the issue voting model Firstly was argued both by Heath, Curtice and Jowell and by Dunleavy and Husbands that individual voting decisions might in reality be influenced mainly by social background factors and/or by the broad images and/or the broad ideologies of the political parties and that when asked about their detailed party policy preferences they would simply adjust their policy preferences to conform to their choice of preferred party. Their judgments on party policies derived from their party preferences decision but certainly did not explain their party preferences or their voting decisions.

- Secondly further criticism of the issue voting model arose in relation to the General Elections of 1983, 1987 and 1992 because it was noted that if voters had indeed voted on the basis of their policy preferences on the most salient issues Labour would actually have achieved far better results than actually occurred in practice .

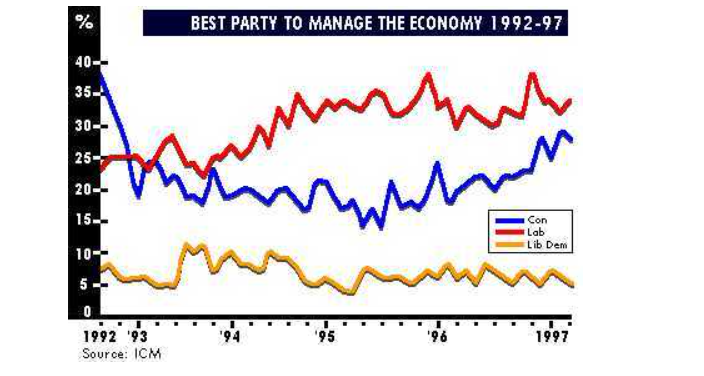

- In relation to these elections it came to be argued that the economy was in fact the most salient issue of all and that the Conservatives won these General Elections partly because they were seen as having the best policies on the economy [a spatial issue] but possibly more importantly because they were seen as most competent to run the economy [a valence issue]. Furthermore it came to be argued that since most voters have insufficient time, interest, time or understanding to follow the minutiae of economic policy their judgments of party competence are likely to be influenced heavily by their perceptions of overall leadership competence which have therefore become much more important determinants of voting behaviour than was believed previously.

- Thirdly we may note that in some respects the description of the voting decision-making process in the issue voting model is presented as a progression away from reliance on ingrained, habitual processes of political socialisation [as in the party identification model] towards increasingly judgmental rational individual decision making However in the dominant ideology model of voting behaviour [to be discussed below] it is suggested that many individual voters can be swayed by the slogans , sound bites and photo-opportunities of apparently charismatic politicians and by the biased coverage of important issues in the mass media so that , whatever else the voting decision may be, it cannot be described as entirely rational. Further information on the dominant ideology model and on criticisms of it is provided below. In particular critics of the dominant ideology model are likely to argue that voters easily recognise and discount political biases within the mass media so that rational, judgmental voting is indeed increasingly possible.

These above points lead us to the general conclusion that although partisan dealignment, class dealignment and overall patterns of voting behaviour may to some extent be explained in terms of the issue voting model, [especially when the importance of the distinction between spatial issues and valence issues is recognised] the ongoing importance of long term party identification on the voting behaviour of many voters must still be recognised as must the importance of other models of voting behaviour to be considered below.

Addition December 2016

In the UK General Elections of 2010 and relationships between social class and voting support for the Conservative and Labour Parties were affected by the general decline in support for Labour [in 2010] and by the rise of the SNP and of UKIP in 2015.

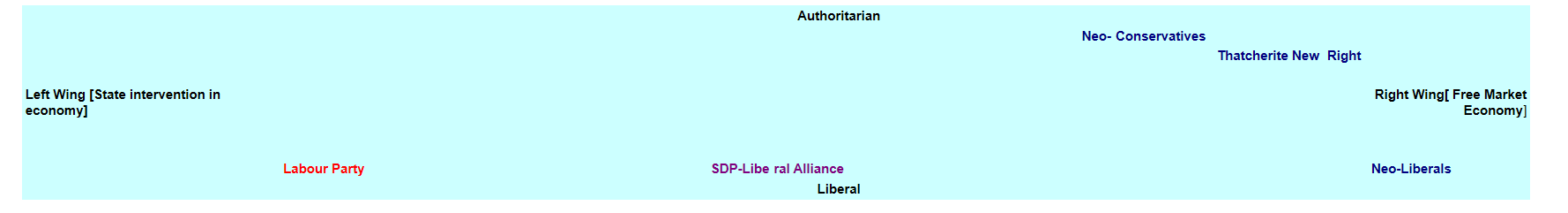

- The Ideological Model of Voting Behaviour

Ideologies may be visualised as containing a horizontal spectrum of left -right economic issues and a vertical spectrum of authoritarian-liberal moral issues and the various ideological positions of the political parties in 1983 are illustrated approximately in the following diagram. Thus Labour's ideology in 1983 was left-wing on economic issues and liberal on social and moral issues while the Conservatives' New Right ideology was right-wing on economic issues and authoritarian on social and moral issues. The SDP -Liberal Alliance ideology could be visualised as perhaps slightly left of centre on Left-Right issues and as liberal on moral issues.

[Remember that the New Right amalgamates neo-Conservatism and neo-Liberalism whose ideological positions are also shown in the table. Note also that in the table the Labour Party, the SDP-Liberal Alliance and the Neo-liberals are all located as equally liberal: this is clearly an extreme oversimplification in that different definitions of liberty may be adopted by these groupings and, also, whereas for Neo-liberals the free market economy helps to defend individual liberty for the Labour Party and for the SDP-Liberal Alliance greater state intervention helps to promote individual liberty. ]

The development of the ideological model of voting behaviour is associated most especially with Heath, Curtice and Jowell's study "How Britain Votes " [1985] . This is a long, detailed, complex study but its main elements may be summarised as follows.

- Individual voters are socialised to accept particular attitudes and values much as in the party identification model but whereas in the party identification model it tends to be argued that most voters' political preferences lack ideological coherence, Heath , Curtice and Jowell argue that in many cases voters' attitudes and values can be combined to form recognisable ideological positions which exercise a major influence on voting behaviour and indeed a more significant influence on voting behaviour than voters' stated preferred policies on the most salient issues of the campaign.

- Most voters vote for the party whose general ideological position is closest to their own general ideological position and on this basis the Conservatives won in 1983 primarily because more voters favoured their general ideological position by comparison with the ideological positions of the Labour Party and the Alliance parties. This does not mean that the Conservatives won because of the growing overall popularity of Thatcherism : they won because Thatcherism was more popular than the decidedly unpopular version of radical social democracy on offer from the Labour Party in 1983.

- Meanwhile the SDP-Liberal Alliances ideological position [slightly left of centre on economic issues and liberal on social issues] attracted votes mainly from disaffected former Labour voters.

- Voters ideological positions derive to a considerable extent from their social class backgrounds as in the party identification model and changes in the class structure involving the relative growth of the "middle classes" and the relative decline of the working class explained perhaps as much as 50% of Labour's decline in popularity between 1964 and 1983.

- However Heath, Curtice and Jowell emphasise that they are not offering a purely deterministic model of voting behaviour in which social class position determines ideological values and ideological values determine voting behaviour.

- Instead it is perfectly possible that political parties can take actions which will increase or reduce their levels of voter support beyond the levels which would be predicted by the overall shape of the class structure. Thus it is argued that in 1983 Labour's more radical ideological position was especially electorally damaging but so too were voters' perceptions of the Labour Party as poorly led, economically incompetent, disunited and saddled with unpopular policies.

- Thus Heath , Curtice and Jowell do not entirely reject the issue voting model : they argue instead that voting behaviour is based mainly on voters' class related ideological positions but that leadership, economic competence, unity and policies on salient political issues also exercise some influence over voting behaviour.

- They themselves state that they are attempting to combine in their model the most useful elements of the party identification and issue voting models.

In summary, therefore, Heath, Curtice and Jowell saw voters' overall perceptions of parties' general ideological positions as more important than specific party policies as determinants of voting behaviour and claim that Labour lost in 1983 partly because of the perceived unattractiveness of its ideological position although they also recognise the importance of changes in class structure, of perceptions of the Labour Party as divided and incompetent and indeed of Labour's unpopularity on some spatial issues such as nationalisation and defence. Heath, Curtice and Jowell and other psephologists have recognised also that it is in practice difficult to distinguish clearly between the effects of party ideologies and party policies on voting behaviour because voters to a considerable extent assess parties' ideologies with reference to their current party policies.

In the aftermath of their electoral defeat in 1983 Labour gradually modified several of their key policies which in sum could be perceived as representing a shift toward the Centre-Left in ideological terms although on the basis of a careful study of General Election manifestos Ian Budge argued that although by 1987 Labour had moved toward the Centre-Left it had in fact moved back toward the Left by 1992, a conclusion based upon the proposed high levels of spending on Health and Education in the 1992 General Election Manifesto. However other analysts would argue that the main objective of Neil Kinnock and his supporters was actually to shift the Labour Party further to the Right between 1987 and 1992 and so some psephological controversy may surround this issue. Be that as it may Labour's electoral performance improved only gradually between 1983 and 1992 and many would explain its relatively poor performances in 1987 and 1992 mainly in valence terms: in particular it was still not perceived as competent to manage the economy.

Under the leadership of Tony Blair Labour move decidedly toward the Right on economic issues accepting Conservative privatisations a, its industrial relations legislation which had restricted the powers of trade unions and its taxation changes which had significantly reduced rates of income taxation especially on the higher paid although it did also attempt to differentiate itself from the Conservatives via its proposals to introduce a minimum wage, its New Deal for the unemployed and initiatives such as the Working Families Tax Credit designed to help low paid workers.

This overall ideological strategy surely paid dividends and it may be argued that Labour's changed ideological position attracted many formers Conservative voters. However since Labour also had the most credible leaders, the most popular policies on most spatial issues and was most popular on valence issues involving general political effectiveness it is very difficult to assess the independent effects of Labour's changed ideology on its electoral support in 1997, 2001 and 2005.

It may be, however .that most voters have seen ideological differences between the Labour and Conservative parties as declining between 1997 and 2005 and as declining even further as the Conservative Party has moved toward the Centre under the leadership of David Cameron. This ideological shift may provide electoral benefits for the Conservatives just as Labour's shift to the Centre helped it to win in 1997.

- The Dominant Ideology Model of Voting Behaviour

The dominant ideology model of voting behaviour may reasonably be seen as one significant element of the more general theory which suggests that the existence of a dominant ideology has a major influence on politically attitudes more generally. Although supporters of the dominant ideology model would not necessarily describe themselves as Marxists it is perhaps fair to say that the principal inspiration for the model is the Marxist notion that " in every epoch the ruling ideas are the ideas of the ruling class" [The German Ideology 1846.]

Thus it is argued that capitalist societies are dominated by a ruling class which is able to maintain its position of economic and political dominance by means of a socialisation process operating via institutions such as the Family, the Church, the Education system, the Political Parties and the Mass Media which persuades members of disadvantaged , subservient social classes to accept that ruling class control is actually also in the best interests of the subservient classes: that is the socialisation process under capitalism results in the transmission of a dominant class ideology which creates false class consciousness among disadvantaged social classes preventing their members from recognising that the capitalist system is the fundamental cause of their disadvantaged situation.

In the dominant ideology model of voting behaviour it is argued that the mass media [and in particular the press] have traditionally been supportive of Conservative political opinion and that mass media influence has persuaded large swathes of working class voters to vote Conservative when in reality it has not been in their interests to do so. Furthermore if and when national newspapers have supported the Labour Party [as in the Blair era] this has been precisely because under the leadership of Tony Blair Labour offered no challenge to the interests of the capitalist class while more recently the election of Mr. Ed Miliband as Labour Party leader has been presented in some sections of the press as evidence of a dangerous "lurch to the Left" under "RED ED" [ the son of the late Ralph Miliband , a famous Marxist intellectual] whose election was made possible only by the disproportionate influence of trade union leaders. [Perhaps there is material here for David Mitchell's True or False Game Show! ]

Critics of the dominant ideology model of voting behaviour may argue that Marxist -inspired analyses of the capitalist system are flawed in that it is actually existing modern capitalism that is most likely to guarantee individual liberties and to generate rising living standards for all; that the mass media are far less biased than is implied in the dominant ideology model and that the activities of the mass media can be explained more accurately in terms of pluralist theories ; that the dominant ideology model overstates the persuasive capacities of the mass media and understates the capacities of voters to make up their own minds; and that insofar as there are correlations between newspaper readership and voting behaviour this occurs because voters choose to read newspapers reflecting their own political opinions not because the newspapers have been able to determine voters' political opinions.

Supporters of the dominant ideology model of voting behaviour argue that even after all of these criticisms are fairly assessed the model does nevertheless make a significant contribution to the overall explanation of voting behaviour.

Click here for some recent information from Democratic Audit on trends in political affiliations of the British press

[Further assessment of the dominant ideology model would require a full discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of Marxist theories, of the organisation, activities and effects of the mass media in general and of studies of the actual influences of the mass media on voting behaviour in particular. Doubtless you will be discussing these issues with your teachers!]

- Key Political Events

Individual elections may well be influenced by key political events. Possible examples include the following.

- The Winter of Discontent of 1978-9 which may have undermined Labour's electoral prospects in the 1979 General Election.

- The Falklands War of 1982 which may have contributed to the increased popularity of the Conservatives during the run in to the 1983 General Election.

- The resignation of Mrs. Thatcher and her replacement by John Major in 1990 which improved the Conservatives' electoral prospects in 1992.

- The ERM crisis of September 1992 which undermined the Conservatives' reputation for economic competence and contributed to their electoral defeat in 1997 .

- The involvement of the UK in the Iraq War from 2003 onwards which in various indirect ways may have adversely affected Labour in the 2005 General Election.

- The MPs expenses scandal and the recent economic recession which adversely affected Labour in the General Election of 2010.

- The rise and fall of UKIP and the SNP which affected the General Election Results of 2015 and 2017.

- The Voting Context Model

So far it has been argued that voting behaviour is influenced to some extent by sociological variables such as class, gender , ethnicity, age, region and religion as in the party identification model; that it is influenced by voters' assessments of party policies on salient political issues, as in the issue voting model; that sectoral cleavages within social classes exercise an important influence as in the radical model; that mass media influences are significant as in the dominant ideology model which also appears as an element of the radical model; and, in the ideological voting model that voters are influenced more by broad ideological factors than by specific political policies on salient issues. All of these models contribute importantly to the overall explanation of voting behaviour.

In the voting context model it is emphasised that although voting decisions are influenced by all of the factors mentioned above ,they also vary according to the differing nature of elections and the differing circumstances surrounding them. In this model it is emphasised that individuals' votes may vary in different elections because of the different constituency characteristics in different types of election, because individuals may have different objectives in different types of election [registering their ongoing support for their preferred option or voting tactically to prevent the election of the least preferred candidate], because individuals may vote according to different criteria in different types of election and because, nowadays although the First Past the Post electoral system is used for Westminster Elections different electoral systems are used in elections to the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly and to the European Parliament and to elect the Mayor of London.

Thus, for example let us imagine that a very strong Conservative identifier lives in a very safe Labour local council ward which is part of a marginal Liberal Democrat -Labour Parliamentary constituency within a marginal Conservative-Liberal Democrat European constituency. In such circumstances one can easily imagine that this strong Conservative identifier might abstain in the local council election, vote Liberal Democrat in the Parliamentary election and vote Conservative in the European election whereas another strong Conservative strong identifier might chose to vote Conservative even if it results in the election of a least preferred candidate. Furthermore if at some point in the future local and parliamentary elections are carried out under some form of PR this too would encourage strong identifiers with all parties to vote for their preferred party.

Voters may also vote according to different criteria in different types of election. In local council elections some voters are more likely to vote for particular candidates rather than for particular parties and on the basis of local rather than national issues which may mean that they vote for different parties in local and national elections. Alternatively their vote in local elections may be influenced by national considerations and they may wish to register a protest vote against "their" party's current performance in government even though they have every intention of continuing to support "their " party in the future general election.

The precise political circumstances surrounding by -elections may similarly influence voting behaviour in unexpected directions. Assume that there are 3 Parties : Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat and that the Labour Party is currently in national government. Supporters of the Labour Party may wish to exercise a protest vote against it but they are probably more likely to switch to the Liberal Democrats than to go so far as to vote Conservative. If Conservative identifiers become aware of this rise in Liberal Democrat support some of them too may switch tactically to the Liberal Democrats as the best means of ousting the Labour candidate while other Conservative identifiers may choose to continue to register their support for the Conservative Party even if it results in the election of the Labour Candidate..

Very useful information on the Voting Context Model [and on voting behaviour in general may be found in British Politics in Focus [ R. Bentley, A. Dobson, M. Grant and D. Roberts 2000] and you may also like to discuss the European Elections of 2009 as an example of elections which were influenced very much by the special political context in which they were held which derived from the controversies surrounding MPs expenses.

Click here for useful information on Tactical Voting in recent General Elections from the BBC General Election 2010 site.

Click here for a good recent item from tutor2u on the Voting Context Model

- Conclusions

It is very difficult to estimate the relative importance of the various factors specified in the models described above on voting behaviour. It is likely that strong party identification has declined significantly since the 1970s but that it nevertheless continues to be a major determinant of voting behaviour for the remaining strong identifiers and for a sizeable proportion of weaker identifiers. Other less committed voters are likely to be influenced in various ways by their perceptions of leadership competence linked to valence issues, by their party policy preferences on specific spatial issues and by their broad ideological preferences.

Furthermore voting decisions may be influenced to some extent by the nature of the mass media coverage of political issues [although controversy surrounds the assessment of the strength of these mass media effects], by random unforeseen political events such as a war, an economic crisis or an expenses scandal and by the voting context of particular elections which may, for example encourage greater tactical voting when the result of the election is expected to be close.

There were significant disputes in the 1980s and 190s around the measurement of the relationships between social class and voting behaviour but it is now generally agreed that social class is a less significant now than it was in the 1950s and 1960s. The overall process of so-called class dealignment has been explained in terms of a combination of sociological factors influencing the character of the social classes and political factors of which the growth of issue voting is perhaps the most significant. It is clear also that the electoral fortunes of the major political parties have been influenced by changes in the shape of the overall class structure involving the relative decline in the size of the manual working class and the relative growth of the middle and upper classes which other things equal could be expected to worsen the electoral prospects of the Labour Party.

These social and political trends encouraged the Labour Party especially to reassess its electoral strategy and the next section of this document focuses on the General Elections of 1992 and 1997.

Click here for IPSOS MORI estimates of the relative importance of Party, Policy and Leadership on Voting Behaviour. This might provoke some discussion!

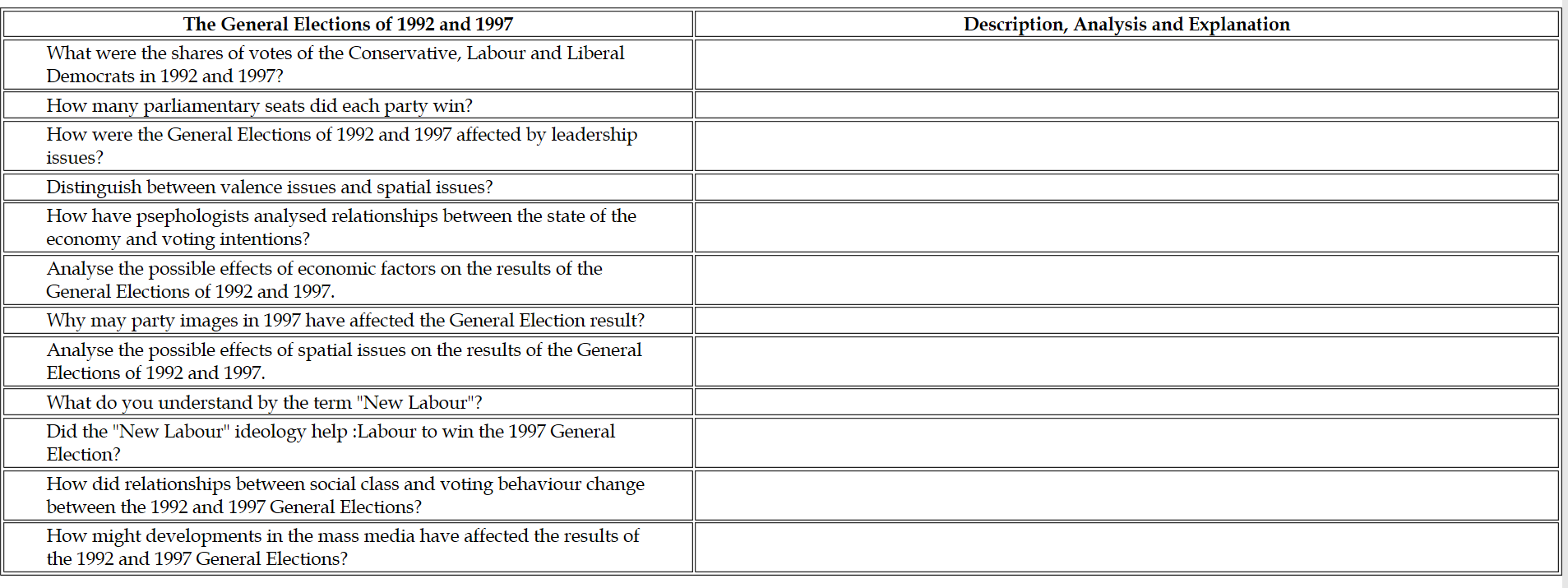

- Document Two: Part B: The General Elections of 1992 and 1997

- The General Election of 1992

BBC Coverage of the 1992 General Election: Once you reach this page you will see that although it is entitled Politics 97.it nevertheless provided good detailed coverage of the 1992 General Election. The links to the left of this page take you to more 1997 General Election pages but for more information on the 1992 General Election you can scroll down to the bottom of the pages and follow the links provided. However I have also copied these links immediately below and again in the section on the analysis of the 1992 General Election result!

Click here for Heath, Curtice and Jowell summary article on the 1992 General Election from the Independent

|

- Introduction

Following Labour's landslide General Election defeat of 1983 it was widely believed by Neil Kinnock and his advisers that Labour would be unlikely to regain office in the future with a traditional social democratic electoral strategy combining egalitarian economic and social policies targeted toward its core working class supporters concentrated mainly among trade unionists and council house tenants] with policies designed to appeal to a relatively small Labour-voting section of the middle class more concerned with issues related to disarmament, the environment and gender politics.

Instead because the working class was contracting numerically and because it was believed also that many more affluent workers were increasingly "aspirational" in their values it was seen as necessary to devise an electoral strategy which would reach out to both working class and middle class voters who had not in the past identified with Labour's traditional social democratic values and policies based around high taxation and high government spending and certainly had not identified with Labour's shift leftward in the early 1980s.

[The measurement of social class presents many theoretical and practical difficulties but in studies of voting behaviour individuals have traditionally been categorised in terms of their occupation by means of the "Social Grade" scheme involving the categories AB, C1, C2 and DE.

Therefore between 1983 and 1987 Labour had attempted to cultivate a more modern, moderate, managerial image and to modify some of its policies: it had expelled Militant Tendency members from the Labour Party and distanced itself from the so-called "loony left" more generally . However for a variety of reasons the Labour Party was again defeated in 1987 and it was then that Neil Kinnock initiated the so-called Policy review which did lead to significant policy changes in readiness for the 1992 General Election. As a result of the Policy Review Labour adopted more market friendly economic policies; it discarded its policies of unilateral nuclear disarmament ; it indicated that Thatcherite industrial relations legislation would be modified but not entirely reversed; and it also scrapped its policies for the nationalisation of the banks although it did still propose to undo some of the privatisations of the Conservative government depending upon the costs involved.

Labour overtook the Conservativesin the opinion polls in late 1989 and given the unpopularity of the Conservatives in the polls , the weakened state of the UK economy, ongoing disunity over Europe and the cabinet reshuffles necessitated by the removal of Sir Geoffrey Howe from the Foreign Office and Nigel Lawson's resignation as Chancellor Mrs. Thatcher's position in government could now be seen as seriously weakened. The Conservatives' position worsened in 1990 as unpopular poll tax bills arrived and precipitated a "poll tax riot" in London and Labour opened up a large opinion poll lead. Michael Heseltine a major potential rival to Mrs. Thatcher, still claimed that there were no foreseeable circumstances in which he would challenge Mrs. Thatcher for the leadership of the Conservative Party. but further dissension over Europe finally prompted Sir Geoffrey Howe's resignation as Deputy Prime Minister , Mr. Heseltine's challenge to Mrs. Thatcher, her failure to win the necessary 15%+ majority on the first ballot, her resignation, the entry of Mr. Major and Mr. Hurd into the leadership contest, Mr. Major's victory in the second ballot, again without the necessary 15%+ majority and the immediate withdrawal from the 3rd Ballot by Mr. Heseltine and Mr. Hurd. Mrs. Thatcher had been replaced as Prime Minister by John Major. but from this point Labour's substantial opinion poll lead began to decline.

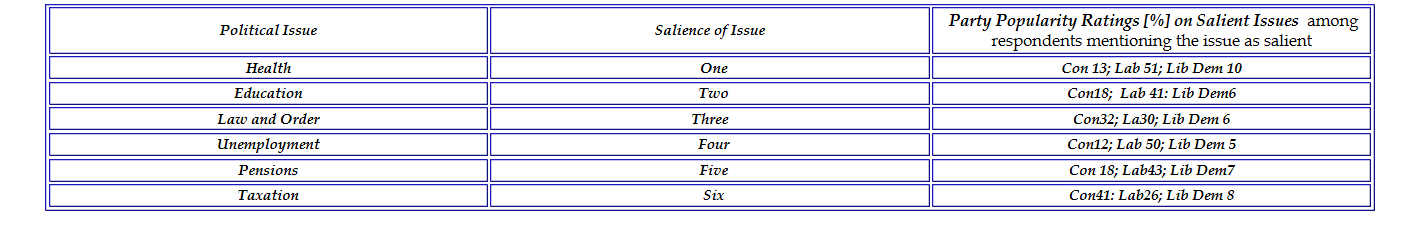

Between 1990 and 1992 the UK economy experienced a deep economic recession which in principle could have been expected to further reduce the Conservatives' chances of electoral victory especially because Labour's traditional opinion poll leads as the most favoured party on highly salient issues such as Health, Education and Unemployment were also well established . Faced with these difficulties Conservative strategists decided that their chances of victory would be much improved if they could undermine the credibility of Neil Kinnock as a future Prime Minister, undermine the credibility of Labour's claims that it could manage the economy with competence and present Labour as the party of high public spending, high taxation and high inflation.

By the time the General Election was called and during the actual election campaign opinion poll data suggested that the most likely outcome was a "Hung Parliament" possibly with Labour as the largest party . However the actual result was to be a great disappointment for Labour as the Conservatives achieved their fourth consecutive General Election victory with an overall parliamentary majority of 21. Although Labour increased its share of the vote by3.6% it did so mainly at the expense of the Liberal Democrats and other parties rather than at the expense of the Conservatives whose share of the vote declined by only 0.4%. Labour had modernised its image; it had discarded some unpopular policies; it had signaled a more business-friendly approach to economic policy and it had still lost despite the fact that the economy was in deep recession. Given that political and economic circumstances in 1992 were relatively favourable to Labour the 1992 defeat was seen as a body blow from which it would not be easy to recover in the future especially because by 1997 the economy could be expected to have recovered and the size of Labour's core vote could be expected to have contracted further. However as former Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson had pointed out many years before, " A week in politics is a long time."

Among the factors suggested for Labour’s defeat in 1992 were the following:

- Spatial Issues and Valence Issues.

Spatial issues are those on which political parties adopt different political positions: [for or against privatisation; for or against increased taxation; for or against increased government spending; for or against greater economic equality; for or against industrial relations legislation sympathetic to the trade unions and so on] whereas valence issues are those on which there is a general consensus among political parties and voters in that for example all political parties and all voters are in favour of increased economic efficiency , improved living standards, better health care and reduced crime and on these issues voters are assumed to choose between the political parties on the basis of their assessments of the likely competence of the political parties to achieve these objectives. Especially important are the voters assessments of the economic competence of the political parties but it is also possible that even if voters approve of a particular party's policies on particular issues they may still doubt the competence of that party to implement its stated policies effectively thereby undermining that party's electoral prospects. Also, if it should be the case that actual differences in party policies on specific issues are small this will obviously increase the significance of valence issues as voters are more likely to vote on the basis of their assessments of overall governing competence.

As we shall see John Major was widely preferred to Neil Kinnock as a potential Prime Minister; the Conservatives were widely perceived as more competent than Labour to manage the economy and the Conservatives were ahead of Labour on the spatial issue of taxation and government spending. These factors more than offset Labour's spatial advantage on the issues of Health, education and unemployment.

- The Importance of Party Leadership.

The new Conservative PM John Major was much more popular with the electorate than was Labour Leader Neil Kinnock.

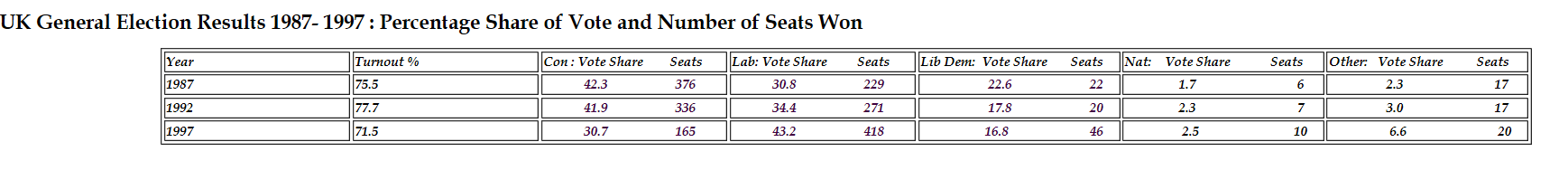

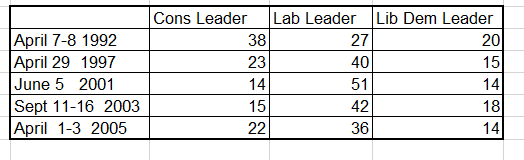

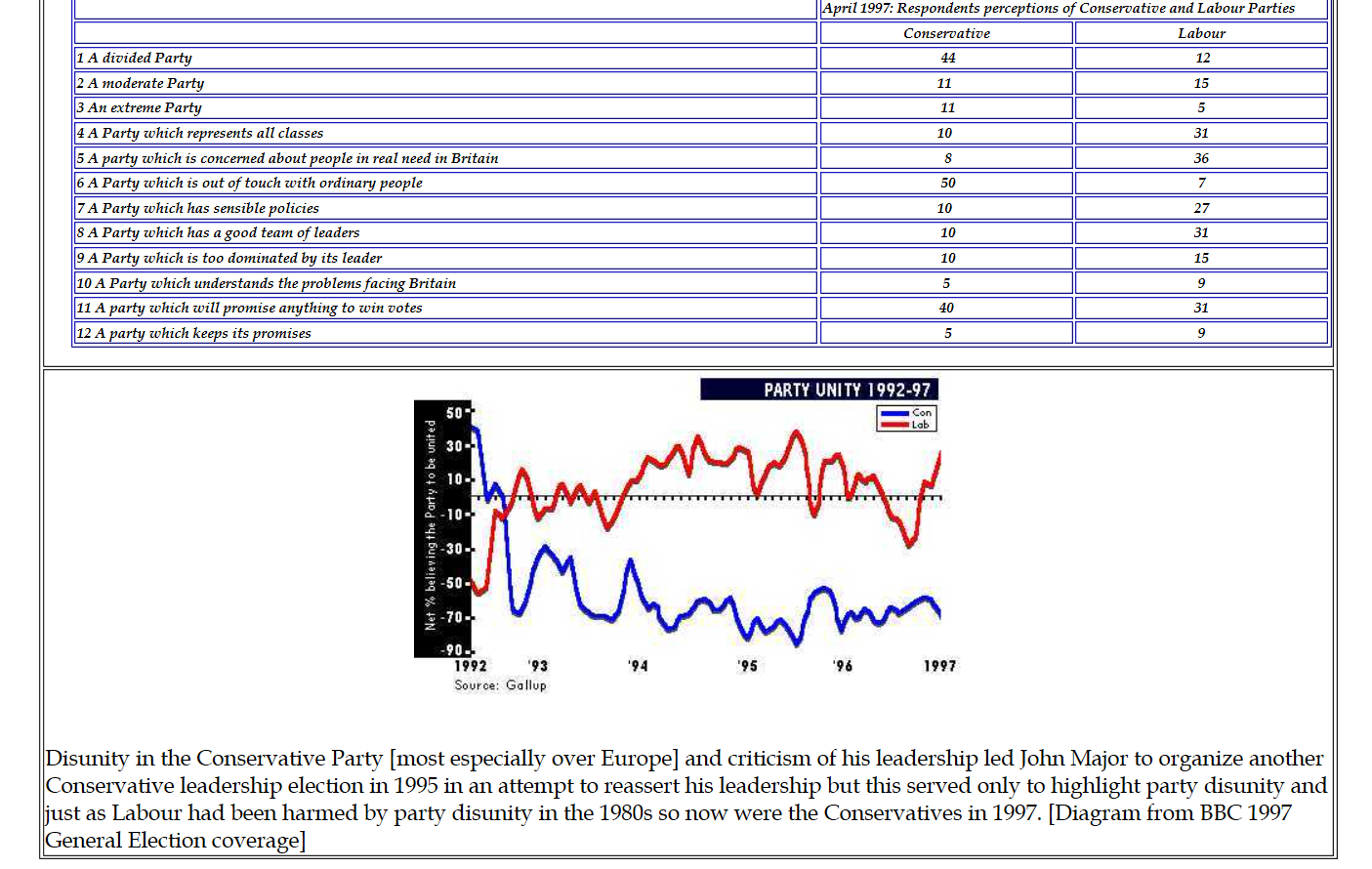

Above is a Chart for data on the relative popularity of partypolitical leaders 1992-2005.Mr. Kinnock had done much tomodernise the image of the Labour Party , to improve party organisation and tointroduce policy changes designedto improve Labour's electoral prospects [although the entire Kinnockstrategy was often accepted only grudgingly, if at all by the more radical Labour Party activists] but he was regarded as a less crediblefuture Prime Minister than John Major partly perhaps because of occasional poorparliamentary performances on important occasions, partly because of earlierpolitical difficulties in the circumstances of the 1984-85 Miners' Strikebut partly also because he was subjected to ceaseless personal attacks inthe pro-Conservative tabloid press.

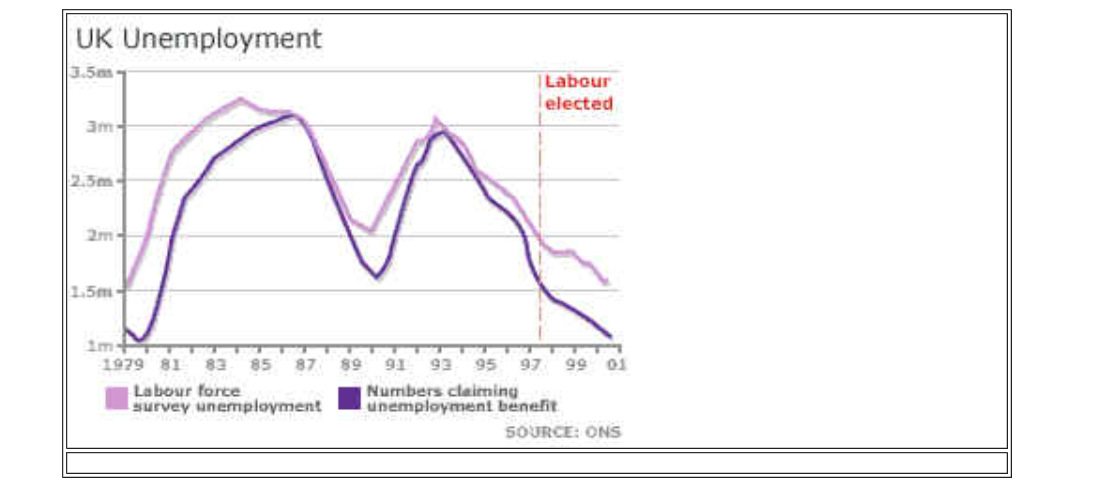

- The Economy

One of the most significant issues affecting voting behaviour is the state of the economy. In 1992 the UK economy was indeed in recession but voters tended to blame the UK recession either on international circumstances over which UK governments have little control or on former Prime Minister Mrs. Thatcher who had had left office in November 1990 and once Mrs. Thatcher was replaced as PM by John Major it almost seemed to many voters that there had already been a change of government [despite the fact that John Major had served briefly as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Mrs. Thatcher's government and was therefore heavily involve in the economic policy making of that government.]