- Click here for Selective Comprehensives: Sutton Trust Report published March 26th 2019 March 2019

- Click here and here for recent statistical disputes over likely impact of Grammar Schools. January 2019

- Click here for When is a comprehensive school actually a secondary modern?

- Click here for Grammar Schools in England: a new analysis of social segregation and academic outcomes: Stephen Gorard and Nadia Siddiqui [V. detailed Paper]

- Click here for summary article by Stephen Gorard about the above paper

- BBC Radio 4: The Briefing Room : Grammar Schools [28 minutes] An ideal starting point. December 2016

- Click here for a 1977 edition of Panorama which presented a not entirely reassuring view of one comprehensive school. This original previous link is broken but you can now click here to access the progamme. There is also a very useful commentary. Let's hope this link will last !

- Click here for a BBC Item: Did Grammar Schools help Social Mobility?

- Click here for a recent Guardian article with links to full spectrum of mass media coverage of proposal to increase number of Grammar Schools. Should provoke discussion!

- Click here for Parliamentary Research Briefing : Statistics on Grammar Schools

- Click here for my PowerPoint Presentation on Tripartism and Comprehensivisation

- Click here for Radio 4 Analysis: A Subversive History of School Reform

- Click here for BBC Radio 4 Analysis programme entitled "Do Schools make a Difference?"

- During September 2016 PM Theresa May has announced her intention to introduce more Grammar Schools. You may click here for my document providing links on Conservative Education Policies 2015-- in which I have asterisked some of the items on Grammar Schools which students may find most useful.

- Click here for Guardian coverage of a new Education Policy Institute report and here for the full report. December 2016

- Click here for Selective Comprehensives [Sutton Trust Report] March 2017

- Click here for recent Guardian article in support of selection March 2017

- Click here for BBC coverage of most recent education policy plans. [Article also has links to the "grammar school debate"] March 2017

- Click here critical assessment of selection by Professor Simon Burgess [from The Conversation] March 2017

- Click here for BBC item on exclusion of grammar school expansion plans from Queen's Speech June 2017

I have revised this document in October-November 2016. It is rather long but I hope that students will be able to use the following links to navigate to sections on the differing aspects of the long debate on Selective and Comprehensive Secondary Education

Document Contents

|

Introduction: An Examination Health Warning

This is are rather long document and Advanced Level Sociology students will not require detailed familiarity with the organisation of the UK education system prior to the 1944 Education Act. The main focus of analysis of education policies in recent years has been upon the broad quasi-marketisation of education which has occurred from1979 onwards . However such quasi- marketisation has had important implications for the analysis of the changing nature of the comprehensive secondary system which may well have changed even more significantly if Prime Minister Theresa May's proposals for the expansion of Grammar Schools were implemented. However once the Conservatives lost their overall majority in the June 2017 General Election there were no proposals for the expansion of Grammar Schools in the subsequent Queen's Speech. Click here for a BBC item on this Queen's Speech

Education Prior to the 1944 Education Act

Prior to 1944 several important government reports were published which recommended the expansion of state secondary education and led eventually to the passing of the 1944 Education.

- Thus the Hadow Report[1926] recommended that the concept of elementary education should be replaced by a system of primary education ending at age 11+ to be followed by secondary education in separate selective and non-selective schools. It also recommended the raising of the school leaving age to 15.

- The 1938 Spens Report confirmed the necessity for secondary education but recommended the expansion of technical high schools thereby clearly helping to lay the foundations for the eventual introduction of the Tripartite system.

- The Norwood Report of 1943 was, if anything, more significant in that although the Norwood committee did receive some submissions in support of "multilateral schools" [in which secondary pupils of all abilities would be educated in a system which approximated to comprehensivisation] it opted for Tripartite Secondary education on the grounds that children basically fall into three categories of ability and that consequently three different types of secondary school were required.

In the words of the Norwood Report Grammar schools were suitable for pupils who "were interested in learning for its own sake", could "grasp an argument" and would ultimately "enter the learned professions" or take up "higher business and administrative posts". Meanwhile the technical schools would be for pupils whose abilities "lie markedly in the fields of applied science or applied art...to prepare boys and girls for taking up certain crafts-engineering, agriculture and the like" and the secondary modern was for pupils who "may have much ability but it will in the realm of facts... and...because he is interested only in the moment he may be incapable of along series of interconnected steps; relevance to present concerns is the only way of awakening his interest: abstractions mean little to him."

Between 1900 and 1944 although many pupils continued to be educated in all age elementary schools between the ages of 5-14, opportunities for secondary education were gradually extended although it is important to note the geographical variation in the nature of secondary school provision. Prior to the 1944 Act [which was devised under the auspices Conservative Education Minister in the Wartime Coalition government R. A. Butler but actually implemented by the Labour government when it come to power in 1945] several types of school were in existence in England and Wales. They are listed below.

- Many pupils between ages of 5-14 still attended a single state elementary school usually with no separation according to age such as nowadays exists although such schools were often organised in separate primary and secondary sections. {I can remember that even in the early 1950s my own Primary school also had a secondary section "next door".}

- However Local Education authorities built an increasing number of Central schools providing secondary education often of a technical nature which resulted in the increasing separation of primary and secondary pupils into separate schools and this process continued especially after the 1926 Hadow report which recommended the ending of elementary education and the transition from primary to secondary school at the age of 11.[In Norwich for example Central Schools were designed for pupils who had been unable to gain a grammar school place but were considered especially suitable for secondary education]

- A relatively small proportion of students from richer families attended private fee-paying primary preparatory schools. [These schools were preparatory in the sense that they were preparing pupils for entry to prestigious public {i.e. private} schools at age 13.]

- Among Private secondary schools it is important to distinguish between the small number of prestigious so-called "Public Schools" which provided a high level[ if traditional] education and the rest of the private secondary schools, many of which educated comfortably off pupils who had been unable to gain places at independent or local authority grammar schools.

- Other comfortably off middle class students might transfer at age 11 from private primary schools to independent fee paying secondary grammar schools some of which had existed for hundreds of years. These schools did also offer a small number of free scholarship places

- Additional secondary grammar schools had been introduced by Local Education Authorities under the terms of the 1902 Education Act. These schools also charged fees but provided more free places than did the independent grammar schools

- After 1902 even more pupils from private primary schools and some from state elementary schools could transfer at age 11 to the newly introduced LEA secondary grammar schools.

- Although the LEA grammar schools were also obliged to provide some free places to pupils who passed the Special Places examination, the vast majority of these free places were awarded to middle class pupils who ,for a variety of reasons, were more likely to pass the Special Places examination and, indeed, some working class pupils [my father included] who passed the examination could not take up their places because of the additional financial costs involved [ such as the costs of the compulsory school uniform].

- By the late 1930s the "Public Schools" were attracting increased criticism even within the "Establishment" because of their elitism and because the education which they were providing was seen as in some respects out of touch with the growing democratic sentiments of the age. It was widely believed that any reform of the educational system should include reform of the public schools but it was not lost on PM Churchill [and on Butler] that reform of the Public Schools would cause political controversy especially in the Conservative Party and, in the event, no such reforms were introduced.

- Also in 1938 one half of elementary schools, catering for just under one third of children were voluntary schools organised primarily by the churches with some financial assistance from the government. One problem for R. A. Butler was that if the school leaving age was to be raised to 15, the Church schools would need additional financial help because many lacked the resources to provide an adequate education even for 5-14 year olds. Eventually these difficulties were more or less resolved.

The 1944 Education Act and the Introduction of Tripartite Secondary Education.

The main provisions of the 1944 Education Act are listed below

- The Board of Education was to become a Ministry of Education and the Minister was given greater powers "not just to superintend but to control and direct Local education authorities."

- The number of LEAs was reduced from to so as to facilitate more effective planning

- There were significant reforms to the voluntary education sector.

- Bearing in mind the geographical diversity of education provision a nation-wide system of primary and secondary education was now to be introduced.

- Parents who wished to educate their children at home would be allowed to do so.

- It was recognised that some children were late developers and there were provisions in the Act for the reallocation of pupils to different schools at age 13.However such reallocations would occur very rarely in practice.

- The school leaving age was to be raised from 14 to 15.However this reform was not actually introduced until 1947.

- Provisions were made for the expansion of further education.

- There was to be increased provision of nursery education, free school meals and medical inspection of school children.

The 1944 Education Act provided for free secondary education for all although those parents who chose to pay for their children's education at private or direct grant grammar schools could still do so. Local authorities were not compelled by the Act to organise secondary education on a tripartite system containing Grammar, Technical and Secondary Modern Schools although the majority of LEAs did opt for Tripartism. Also although the act did not envisage that selection within the tripartite system would be based only upon an 11+ examination, the fact that the availability of grammar school places exceeded the demand for them meant that an 11+ examination containing an IQ tests and English and mathematics tests was introduced essentially as a rationing device. Given the wide acceptance of the views expressed by Cyril Burt and others that it was indeed possible to define and measure intelligence accurately by means of IQ tests and that children with different levels of intelligence could best be educated separately and the support for tripartism emanating from Central Government it was unsurprising that most Local Education Authorities opted for tripratism.

Click here for Guardian article "Anniversary offers Opportunity to dispel Butler Myths".

The following arguments were used in support of the provisions of the 1944 Education Act

- Regional variations in the availability of separate secondary education and the stigma of the term "elementary education" would be ended.

- Different kinds of secondary education would be developed [as it transpired mainly in different types of secondary schools] to meet what were believed to be the different abilities, aptitudes and interests of different types of pupil.

- Allocation to selective state grammar schools would now be determined only by the pupils' academic ability and not by parental financial ability to pay. Thus although there were huge geographical variations it was estimated that in 1938 only 48% of LEA Grammar school places were free places gained via success in entrance examinations. As a result of the introduction of the 1944 Act all such places would be free.

- Any selection process was presented not as a matter of success or failure but as facilitating the allocation of pupils to schools assumed to be suitable for them.

- Although Grammar, Secondary Modern and Technical schools were clearly different they were to be accorded parity of esteem by government in terms of the financial resources devoted to each type of school .

The historian Rodney Lowe has stated that on the one hand the 1944 Education Act "enjoyed enormous popular support" and that it was once described as "the greatest measure of educational advance since 1870 and probably the greatest ever known" but that on the other hand "one educational historian [H.C Dent 1988} has gone so far as to attack the Act as " a clever exercise in manipulative politics by a past master in the art [of the possible] with the aid of a state bureaucracy devoted to highly conservative objectives." [Politics has sometimes been defined as " the art of the possible" and R. A. Butler chose this same phrase for the title of his autobiography.] It is certainly the case that sociologists have been quick to criticise the Act and it is to these sociological criticisms that we now turn.

Sociological Criticisms of Tripartite Secondary Education.

- It was argued that the existence of the 11+ reduced the flexibility of primary schools to determine their own curricula by forcing them to gear their teaching to the demands of the 11+ examination. Of course it was also argued conversely that examination pressures were " a good thing."

- At the time of sitting the 11+ examination the age of children varied from approximately 10.5 to 11.5 and this must presumably have given older children a relative advantage. However it is difficult to see how this problem could be resolved.

- In order to allocate children within the tripartite system it was deemed necessary to assess their intelligence but many doubtwhether the concept of intelligence can be defined with precision.

- It is doubtful also whether children can be classified as "academic", "technical" or "practical" as suggested in the Norwood Report so that the basic rationale for tripartism may well have been s flawed.

- Children were to be allocated to secondary schools on the basis of an 11+ examination involving a so-called IQ test and English and Mathematics tests. It was argued by psychologist Cyril Burt and his supporters that IQ tests could provide an accurate, objective measure of intelligence but this view was called into question on the grounds that some children might be unable to do themselves justice because of "examination nerves": that the tests might contain cultural biases; that some children might be given greater opportunities to practise IQ tests because they were in higher streams of primary schools and /or because they had private coaching and practice could be shown to improve IQ test performance very significantly.

- [Considerable controversy has surrounded the work of Cyril Burt in that he has been accused of fabricating parts of his research .There have been some attempts to restore his academic reputation in recent years although these attempts have also been hotly contested. I shall not pursue this controversy here.]

- It transpired that, for whatever reasons, girls were likely to score considerably higher marks in the 11+, so much so that it was considered necessary to set the pass mark higher for girls than for boys to prevent girls from gaining a disproportionate share of grammar school places. Policy makers claimed that girls had developed more quickly and that boys would soon catch up!

- More Grammar school places were available in some regions than in others and there were also more places in middle class areas than in working class areas.

- Consequently it came to be argued that as many as 10% of pupils may have been allocated to the "wrong" schools via the 11+ and very few of these mistakes were corrected by subsequent reallocation at age 13.

- The Act stressed that different types of secondary school were to receive parity of esteem in terms of provision of financial resources but in practice LEAs often allocated more funds to grammar schools and, in any case, since it was clear that grammar school pupils would, as a result of the education they received, enjoy far better career prospects, it was inconceivable that the different types of secondary school would have parity of esteem in society as a whole and secondary modern pupils were as a result likely to be stigmatised at an early age as 11+ failures.

- Despite the provisions of the Act few new technical schools were built so that in many areas the system of secondary education was virtually bipartite rather than tripartite. Also it was the pupils who had narrowly failed to gain a grammar school place who were allocated to Technical schools but without any specific assessment of their technical abilities

- Neither were any reforms of the private sector of education introduced.

- Researchers such as Heath, Halsey and Ridge concluded in their 1980 study Origins and Destinations that the 1944 Education Act did not increase the degree of meritocracy of the UK system but even by the early 1950s increasing recognition of the limitations of tripartism began to increase support for a transition to Comprehensive Secondary Education

There had been opposition to Tripartism and support for comprehensivisation in some more radical sections of the Labour Party even prior to the 1944 Act but the new Labour Government which was elected to power in 1945 was content to see secondary education organised primarily on Tripartite lines in the belief that the abolition of fee paying in Local Authority controlled Grammar schools would result in increased equality of educational opportunity as more talented working class pupils would now be enabled to enter Grammar schools on the basis of their success in a competitive examination.

The successive Conservative governments of 1951-1964 were also in favour of the Tripartite system and when a series of government reports pointed to the weaknesses of the secondary education system Conservative Ministers tended to respond by arguing that it was therefore necessary to make the Tripartite system work as had originally been intended rather than to recommend transition to Comprehensivisation although by the early 1960s Conservative Secretary of State for Education Edward Boyle did express more sympathy for Comprehensivisation. He did, not, however, remain in that post for long.

The Crowther Report of 1959 demonstrated that the organisation of secondary education was leading to a waste of talent which undermined economic and social progress. The report pointed out that only 12% of pupils were continuing their education until the age of 17 and that early leaving was especially likely for working class pupils even when they had the ability to benefit from further schooling.

The 1963 Newsom Report entitled "Half Our Future" investigated the education of secondary modern pupil and while recognising the high quality of some secondary modern schools, also provided severe criticisms. It was clear that many pupils, even if they had been classified as11+ failures were not given sufficient opportunities to develop their talents in secondary modern schools. W. Kenneth Richmond [1979] wrote as follows in relation to the Newsom Report: "It revealed that nearly 80% of Secondary Modern school buildings were seriously deficient, that the qualifications of Secondary Modern school teachers were often "below average" as their pupils were said to be, that the rapid turnover of staff vitiated the work of schools in the poorer districts---in short that more than half the nation's children were getting a raw deal."

Meanwhile, however, increasing numbers [from 5,500 in 1954 to about 55,000 in 1964]of Secondary Modern school pupils were remaining in school until age 16 in order to take GCSE O level examinations and the trend toward leaving at age 16 could be expected to increase as a result of the introduction of the CSE in 1963 which could be expected to give Secondary Modern pupils a greater sense of direction and may also have acted as a safety net for pupils who attempted but failed the O level examinations. While increasing numbers of Secondary Modern school pupils were attempting O levels sociological studies such as Education and the Working Class and Hightown Grammar demonstrated the wastage of mainly working class talent at grammar schools as many mainly working class grammar school pupils actually left school at age 15 prior to taking O levels.

The Robbins Report of 1963 was not specifically concerned with secondary education but with the necessity for the mass expansion of higher education as a means of increasing economic growth [although the precise relationships between the expansion of higher education and economic growth are difficult/impossible to quantify exactly.] The report recommended that access to higher education should be increased from 216,000 students in 1963 to 560,00 in 1980-81 which resulted in the founding of several new universities and the expansion of the then Polytechnics which were enabled to introduce more degree level courses under the auspices of the newly introduced Council for National Academic Awards. However the significant implication of the Robbins Report for Secondary Education was that it criticised the fundamental ideas that academic abilities were mainly innate rather than culturally determined and that there existed only a very limited pool of talent containing those individuals with the abilities necessary to benefit from Higher Education.

It is clear therefore that in various ways, the Crowther, Newsom and Robbins Reports all helped indirectly to undermine the rationale for Tripartite Secondary Education.

The Transition to Comprehensive Secondary Education

The Labour Party in opposition decided from 1951 to support comprehensive secondary education although the precise meaning of and rationale for comprehensive education was not always made clear by senior Labour leaders who sometimes attempted to popularise the misleading but nevertheless attractive slogan that comprehensivisation would guarantee a grammar school education for every secondary school child. By the early 1960s some senior Conservatives also were giving tentative support to comprehensivisation again without clarification of its precise meaning.

It seemed very unlikely in the early 1960s that all Local Education Authorities would wish to abolish their Grammar schools and unlikely also that the central government would force them to do so but where grammar schools continued to exist any secondary modern schools in these areas which were designated "comprehensive" would be "comprehensive" in name only because they would not contain sufficient numbers of "high ability" children to qualify as "all ability schools." The continued existence of a relatively small number of state grammar schools and private secondary schools still compromises the comprehensive principle [as perhaps do some aspects of recent governments 'education policies to be discussed later]. More uncertainties arose as some educationalists emphasised that comprehensives should and would rely more heavily on mixed ability teaching rather than upon rigid streaming, banding or setting and that as well as providing a more effective academic education, they could also foster social cohesion and reduce class antagonisms via the greater interaction of children from different social backgrounds.

However despite all the uncertainties surrounding comprehensivisation, it came as no surprise, bearing in mind the above mentioned criticisms of the tripartite system, when support for comprehensivisation began to increase in the country as a whole especially as the vast majority of secondary school pupils were being educated in secondary modern schools which were widely unpopular. However the parents of children who had achieved prestigious Grammar school places were usually rather less keen to support the transition to comprehensivisation.

Clyde Chitty and the late Caroline Benn[1996] quote the brief official definition provided in 1995 by the then DfE [subsequently the DCFS and now the DfE again!] of comprehensive schools as "schools which cater for all children irrespective of ability" and provide the following data on the expansion of Comprehensive Secondary Education. [The authors do provide several explanatory footnotes which clarify in detail the coverage of these statistics {see "Thirty Years On" p88} but I have omitted these since I wish only to show the extension in broad terms of Comprehensivisation.]

Secondary Schools in England and Wales 1950-1994:The Expansion of Comprehensivisation.

| Year | % of Pupils | No. of Pupils | % of Schools | No. of Schools |

| 1950 | 0.4 | 7988 | 0.2 | 10 |

| 1965 | 8.5 | 239,619 | 4.5 | 262 |

| 1977 | 78.6 | 2,982,441 | 70 | 3083 |

| 1994 | 86.9 | 2,715,013 | 80 | 3095 |

More recent official data may be found by clicking here.

It should be noted that although the official definition of "Comprehensive" does enable schools to be classified into Grammar, Secondary Modern and Comprehensive more or less accurately in terms of the official definition , the overall nature of the Comprehensive system must be investigated more carefully.

- Even within a local authority are which has abandoned selection by examination completely there may be considerable variation in the pupil intakes of different formally comprehensive schools.

- It may be that former grammar schools turned comprehensive may have better academic reputations than former secondary moderns turned comprehensive and are therefore able to attract more pupils with higher measured ability.

- It may be that the said grammar and secondary modern schools were more likely to have been located in middle and working class areas respectively and hence more likely to attract middle and working class pupils respectively they become comprehensive.

- For a variety of reasons middle class pupils are more likely than working class pupils to achieve good examination results which is likely to solidify the respective reputations of different comprehensive schools .

- Thus the ability ranges of many schools which are officially defined as Comprehensive may be such that they approximate more to Secondary Modern schools or in some cases to Grammar schools rather than to Comprehensive schools .

- It has been argued convincingly that especially in the current era of greater parental choice, middle class parents have greater knowledge than working class parents as to the relative examination success rates of comprehensive schools and have used various strategies not available to working class parents [such as for example purchasing houses in the catchment areas of successful comprehensives] to gain access for their children to the more successful comprehensives. Consequently it is claimed the replacement of Tripartite Education by Comprehensivisation has resulted in the replacement of selection by ability by selection according to parental income. Nevertheless Conservative , Labour and Liberal Democrat politicians have argued that the development of a quasi=market in education has lead to greater competition which has improved educational efficiency and overall levels of educational achievement although this is a view which has also been widely criticised.

- A Sutton Trust Report provided some evidence of social selectivity at top performing comprehensive school and it may well be that some social selectivity exists throughout the comprehensive system. Click here for BBC coverage of Sutton Trust Report: top comprehensives more socially exclusive than grammar schools [2010]

Thus as we consider the possible arguments for and against comprehensivisation we must recognise the existence of the variability which exists within the comprehensive system, a variability which has increased in what some analysts have called the "post-Comprehensive era" which will be discussed later in this document.

The Case For Comprehensive Secondary Education.

The strength of the support for comprehensive secondary education derived from the widely perceived defects of the Tripartite system and from the belief that the Comprehensive system would be able to overcome them.

- Supporters of Tripartism had claimed that there was only a "limited pool of talent" containing the minority of pupils with the abilities to benefit from an academic Grammar school education. However it came increasingly to be argued that many Secondary Modern pupils , some of whom were just as able as Grammar school pupils, were being denied an education suitable to their talents which undermined their quality of life and economic efficiency as adults.

- Supporters of Comprehensivisation argued that pupils' academic talents were not heavily pre-determined at an early age and the talents of the vast majority of students who were failing the 11+ could be increased if they were given greater encouragement and better educational opportunities as was far more likely to occur in Comprehensive schools than in the Secondary Modern schools. Neither, it was claimed, was there any good reason why the progress of the apparently more talented Grammar school pupils would be restricted if they were educated in Comprehensive schools.

- The 11+ examination had been presented by the supporters of Tripartism as an objective, accurate and fair method for the allocation of pupils to the three types of secondary school but critics argued that it was neither objective, nor accurate nor fair. In practice it discriminated in favour of middle class pupils who were more likely to be in the highest stream of "11+ oriented" primary school and whose parents could, if necessary, also afford additional private coaching; although the 11+ IQ test purported to measure abstract reasoning ability it also contained some cultural biases which favoured middle class children; and its existence inhibited the flexibility of primary schools to design curricula more relevant to the needs of their young pupils. Comprehensive schools were to be all-ability schools which at a stroke would remove any need for an examination to determine school allocation.

- Despite government claims that Grammar, Secondary Modern and Technical schools would receive parity of esteem in terms of the financial resources to be spent on the different types of school it became apparent that some LEAs were allocating disproportionate resources to Grammar schools and that in some , but certainly not all, Secondary Modern schools, teaching quality, resources and overall school atmosphere left much to be desired. Also the higher social status of Grammar schools and the better career prospects open to Grammar school pupils ensured that there would be no parity of esteem in society as a whole.

- Consequently pupils allocated to Secondary Modern schools were likely to feel that even at such an early age they had been classified as failures with adverse consequences for their future educational prospects as labelling theorists increasingly argued from the 1960s onwards.

- However since all comprehensives were in principle to educate pupils of all abilities who were not to be selected on the basis of a competitive examination, it was claimed that all comprehensives would have parity of esteem and the dangers of negative labelling would be much reduced especially if the new comprehensives opted mainly for mixed ability teaching which would reduce the negative impact on lower stream/band/set pupils of streaming/banding/setting.

- It had been recognised that under the Tripartite system there would be some "late developers" who although allocated to Secondary Modern schools at age 11, might show , say by the age of 13 that they should be reallocated to Grammar or Technical schools. Some provisions were made for reallocations between schools but they were rare in practice and it was` pointed out that reallocations between streams/bands/sets within individual comprehensive schools would be far simpler than reallocation between schools as under the Tripartite System.

- Comprehensive schools, especially those in urban areas, were to be relatively large which would enable them to provide economically a wider range of courses than was available in the smaller Secondary Modern schools. It was argued that relatively large size would be necessary to ensure that there would be sufficient numbers of high ability students in the schools to differentiate them from Secondary Modern schools and to positively affect their overall ethos . Most Comprehensive schools [again, especially those in urban areas] would also provide Sixth Form facilities and it was hoped that the Comprehensive system would ,via more effective teaching, enable a greater proportion of students to complete A level courses and move on to Higher Education than had been the case under the Tripartite System in which very few Secondary Modern pupils had remained in school beyond the then compulsory school leaving age of 15 although from the late 1950s increasing numbers did so..

- It was hoped also that because Comprehensives were to offer A level courses this would enable them to attract more highly qualified staff who would be attracted by the possibility of teaching such courses.

- As has briefly been mentioned it was hoped by many supporters of comprehensivisation that if the vast majority of secondary school pupils were educated in similar comprehensive schools more regular social interaction among pupils of different academic abilities and social backgrounds could help to drive up academic standards and make for greater social cohesion which would be socially beneficial in the long term

- In summary, therefore ,it was hoped that the new comprehensive schools would be popular with pupils and parents alike and that all pupils would now have a fairer chance in a more effective teaching environment to develop their talents to the full thus reducing the inequalities of opportunity and the wastage of talent [especially among working class pupils] which occurred under the Tripartite system.

Opposition to Comprehensive Secondary School Education.

Supporters of Comprehensivisation continue to accept most of the above arguments and to believe that it has provided far better educational opportunities for pupils who would otherwise have been educated in Secondary Modern schools while simultaneously enabling pupils who would otherwise have been educated in Grammar schools to continue to reach high academic standards.

However several important criticisms have been made of Comprehensive Secondary Education.

Click here for a 1977 edition of Panorama which presented a not entirely reassuring view of one comprehensive school.

- Supporters of the selective Grammar schools argued that these schools provided an excellent academic education for the limited pool of higher ability pupils who would benefit from the academic stimulation and competition which derived from the concentration of higher ability , ambitious[ and disproportionately middle class] pupils in the Grammar schools. Brighter pupils, it was claimed, were more likely to drift rather than to excel in the less challenging atmosphere of comprehensive schools.

- It was clear also that many supporters of Grammar school opposed the greater social mixing of pupils which was likely to occur under comprehensivisation on the grounds that such social mixing might undermine the high standards of behaviour and positive attitudes to learning which themselves contributed to high academic standards in the Grammar schools.

- Supporters of comprehensivisation had often argued that insofar as comprehensive school would be larger than the Secondary moderns that they replaced this would enable them to offer a wider range of courses in a cost-effective manner. However critics argued that large comprehensives would become impersonal institutions in which pupils' individuality would be lost with adverse consequences for them.

- It was rapidly argued by some critics of Comprehensivisation that overall examination results were worse than had been achieved under the Tripartite system, a view rejected by supporters of comprehensivisation. This so-called standards debate [which has become even more complex amid claims and counterclaims as to trends in the degree of difficulty of GCE O level, GCSE and A level examinations] is according to many experts impossible to resolve with any certainty while the well known supporter of comprehensivisation Clyde Chitty has pointed out that any such debate in any case ignores the impacts of the different systems on the very large numbers of pupils who have in any case never been able to achieve the 5 Olevel/A*-C GCSE standard and that one argument in support of Comprehensivisation is that it can provide better educational opportunities for these children. {I shall not attempt to summarise the conclusions of this complex statistical debate and interested leaders will have to consult the more specialist literature for themselves!]

- There have also been important disputes surrounding the use of mixed ability teaching within Comprehensive schools. Some critics opposed Comprehensive schools on the grounds that the widespread use of mixed ability teaching would hamper the progress of high ability pupils whose learning speed would be restricted by the necessity for mixed ability classes to be taught at a pace which could be followed by the slower learners. It was also sometimes claimed that the slower learners would actually be demoralised by too frequent comparison with their apparently much cleverer peers.

- Against this, however, some supporters of comprehensivisation argued that greater reliance on mixed ability teaching would improve the standards of the weaker students as a result of the decline of negative labelling without reducing the progress of the cleverer pupils.

- Many sociologists have produced studies pointing to the adverse consequences of streaming /banding/setting operating via negative labelling but many Comprehensive school teachers continue to see merit in streaming/banding/setting.

- Some radical supporters of comprehensivisation criticised the practices of actual comprehensive schools which in their support for streaming/banding/setting were doing little more than retaining the system of tripartism under one roof.

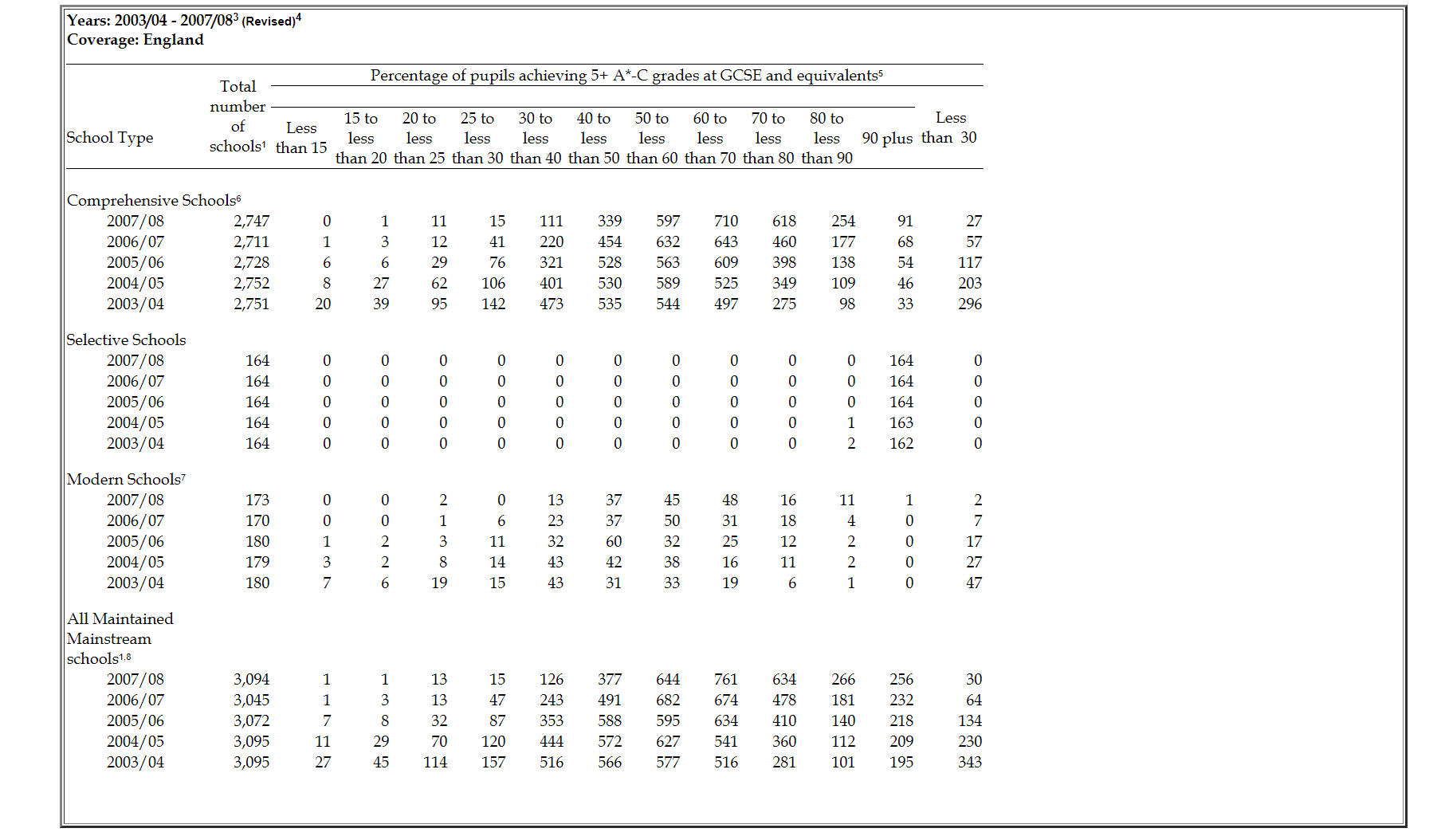

- There were and remain very significant differences among Comprehensive schools with the result that parity of esteem among comprehensive schools is unlikely to be achieved just as was the case under the Tripartite system. A glance at the GCSE examination statistics shown in the following table will show why comprehensive schools re unlikely to be given parity of esteem by parents, pupils and employers.

- It has been argued convincingly that especially in the current era of greater parental choice, middle class parents have greater knowledge than working class parents as to the relative examination success rates of comprehensive schools and have used various strategies not available to working class parents [such as for example purchasing houses in the catchment areas of successful comprehensives] to gain access for their children to the more successful comprehensives. Consequently it is claimed the replacement of Tripartite Education by Comprehensivisation has resulted in the replacement of selection by ability by selection according to parental income. Nevertheless Conservative , Labour and Liberal Democrat politicians have argued that the development of a quasi=market in education has lead to greater competition which has improved educational efficiency and overall levels of educational achievement although this is a view which has also been widely criticised.

- The following table on GCSE examination results in different types of school show some very interesting comparisons. [These data are now a little dated but similar variations remain in the examination pass rates of different comprehensive schools.

In relation to the above table you might like to note the following main points.

The data apply to only to the State sector of secondary education in England. No results for private schools are presented

GCSE examination results vary very considerably among different comprehensive schools but since results depend to a considerable extent upon the social circumstances of the pupils as well as on the effectiveness of the schools themselves we cannot automatically assume that the schools with the best results are the most effective schools. It is for this reason that governments attempt to assess school effectiveness in terms of value added to their pupils' attainment levels. You may wish to discuss the value added concept with your teachers.

In recent years in all selective schools 90% or more of pupils have achieved 5 or more A*-C grades at GCSE Level. Since these pupils will have undergone fairly rigorous selection procedures and may also come mainly from relatively affluent social backgrounds these results are perhaps not entirely surprising.

Very few Secondary Modern schools contain large percentages of pupils gaining 5 or more A*C GCSE pass grades because they are located in areas where most pupils with high measured abilities at age 11 attend selective secondary schools.

Comprehensive Education in the Post-Comprehensive Era?

Especially from 1965 onwards the process of comprehensivisation in England, Scotland and Wales accelerated and by 1997 there were only 165 selective Grammar schools and a similar number of Secondary Modern schools by comparison with more than 3000 Comprehensive secondary schools while around 7% of Secondary school pupils were being educated privately. Criticism of comprehensive schools was fuelled in the 1970s by authors of the so-called Black Papers whose ideas were to a considerable extent accepted within the Conservative Party and there were consequently been significant changes between 1979 and 1997 to the nominally Comprehensive system as successive Conservative governments created new kinds of secondary schools and modified the organisation of schools in ways which ,according to some supporters of comprehensivisation, could be seen as undermining the Comprehensive ideal. Thus between 1979 and 1997:

Some comprehensive schools had been designated as grant maintained schools and allowed to opt out of the state system;

City Technology Colleges had been introduced. [They were to be located in deprived Inner City areas and to be part financed by business sponsorship. In the event only 15 CTCs were introduced primarily because businesses proved unwilling to provide sufficient financial assistance for them although they could, however, be seen as precursors of the Academies subsequently introduced by Labour.

The ERA had resulted in the expansion of the more popular secondary schools at the expense of other less popular secondary schools;

Specialist schools had been introduced in 1992. These schools received additional state funding and were allowed to select up to 10% of their pupil intake on the basis of aptitude/ability in the schools' specialist subjects. The number of Specialist Schools increased significantly under subsequent Labour Governments..

Under Conservative Governments [1979-1997] [and Labour Governments [1997-2010]] the development of education policy was influenced by a so-called diversity and choice agenda which resulted in the growth of a quasi-market in secondary education which reflected the influence the principles of Public Choice Theory and Neo-Liberalism/Market Liberalism .Neo-Liberals claim that just as in the capitalist economic system consumer choices between alternative goods and services result in the relative expansion of efficient companies at the expense of inefficient companies increased parental choice of schools would have similar beneficial effects in the education system. Parents would now be able to choose among different primary schools and different types of secondary school[ Private, Grammar, City Technology Colleges, Opted Out Grant Maintained Schools and Comprehensive Schools remaining under LEA control, some [not all] of which would in 1992 be designated "Specialist Schools" thereby introducing further diversity into the secondary sector] . According to Neo -Liberals/Market liberals these parental choices combined with the new funding system based upon pupil numbers would result in the relative expansion of effective schools at the expense of ineffective schools leading to the improvement of overall educational standards.

However several education policy analysts were critical of the neo-liberal approach was indicated especially in the work of Ball , Bowe and Gerwitz . In their study "Markets, Choice and Equity in Education " [1995] Ball, Bowe and Gerwirtz criticised Conservative education policies designed to provide parents with a wider choice of schools for their children because in their view middle class parents and their children would be especially likely to benefit from this choosing process because they possess the cultural and economic capital to choose more effectively. With regard to parental choice, Gerwirtz, Ball and Bowe distinguish between mainly middle class "privileged choosers" and mainly working class "semi-skilled and disconnected choosers" admitting however that these categories are , to some extent ideal types and that many parents may be difficult to classify exactly.

Privileged choosers are overwhelmingly middle class and are likely to opt either for private education or for the more successful state schools. To achieve this objective they may have purchased expensive houses in the catchment areas of effective state secondary schools; they may have chosen Middle Schools which are known to have especially good links with effective secondary schools ; they can afford to organise any necessary transport arrangements if the required schools are some distance away; they are both willing and able to take the time to assess information relating to examination results and related issues; they are comfortable in discussions with teachers and also ready to challenge them if they feel it to be necessary; they are familiar with sometimes complex application processes all of which puts them at an advantage in securing their children's entrance to the more effective schools.

By contrast "disconnected choosers" are primarily working class and are more likely to opt for their local neighbourhood school which consequently is likely to have a more working class intake. These parents certainly do show considerable interest in their children's education but their choice of secondary school is often not seen as especially important because "they typically see all schools as much the same". For this reason they are very likely to choose the secondary school in their own neighbourhood partly for reasons of convenience and partly because financial and time constraints inhibit their abilities to organise transport to more distant schools. They may also be influenced by friends, neighbours and relatives with similar views and their choice of school may to some extent reflect their sense of belonging to their own local, working class community. Thus the authors conclude that " choice is very directly and powerfully related to social class differences" and that " choice emerges as a major new factor in maintaining and indeed reinforcing social class differences and inequalities".

The ERA has also had important implications for the organisation of schools themselves as they must give more attention to marketing methods if they are to maintain student numbers and especially if they are to attract the middle class children who are most likely to boost league table performance. Individual schools may have some freedom of manoeuvre to decide upon their response to the implications of the ERA and if Governors, Head teachers and senior staff are very committed to the ideals of comprehensive education and do not face strong competition from rival schools the impact of the ERA may be limited . However this is unlikely and Ball et al suggest that the 1988 Education Reform Act has influenced school policy in several ways: it is more likely that resources may be diverted from actual teaching to improvements in the school buildings; new reception areas may be built; more professional prospectuses may be designed; open evenings are carefully choreographed; music and drama may be given a higher profile partly in and attempt to appeal to middle class parents.

Insofar as successful schools succeed in attracting increasing numbers of mainly middle class pupils via careful marketing of the good examination results the financial resources available to less successful schools in mainly working areas will decline leading to declining educational opportunities for the mainly working class pupils who still opt to attend these schools. The processes of increased parental choice under the terms of the Education Reform Act 1988 were therefore likely to result in increased inequality of educational opportunity.

Nevertheless in general terms New Labour under Tony Blair accepted much of the Thatcherite neo-liberal agenda while at the same time claiming to support a modernised version of social democracy which would be more in tune with the demands of an increasingly globalised world economy [all of which has been described , accurately or otherwise, by left wing critics as amounting to little more than "warmed over neo-liberalism" or "Thatcherism with a smiling face"] and he also showed himself to be ready to accept much of Conservative Education policy although New Labour would also introduce a range of compensatory measures which many argued were informed by a recognisably social democratic political philosophy .

[clicking here for the New Labour approach to Compensatory Education]

By 1997 there were increasing concerns within the Labour government and elsewhere that educational standards in some comprehensive schools were in serious need of improvement. Inspectors reported that lessons were often badly taught , that pupil discipline was poor and that although GCSE results were gradually improving more than 50% of students nationally were failing to achieve 5 or more A*-C grades and in many comprehensive schools with primarily working class intakes only 15% - 30% of students were gaining the 5 A*-C grades.

Schools Effectiveness Research indicated too that there were wide variations in examination results in schools with similar socio-economic intakes thus demonstrating that variation in examination results was caused at least partly by variation in the quality of the schools themselves and not only by socio-economic conditions external to the schools. New Education advisers brought in by Tony Blair such as David Miliband, Andrew Adonis and Michael Barber recommended that the Comprehensive system was in need of reform.

It is likely that in the mid 1990s Tony Blair, David Blunkett and their policy advisers believed that the Labour Party was identified too closely in the electorate's mind with uncritical support for progressive education and the comprehensive principle and with dogmatic opposition to grammar schools , private education and to recent Conservative reforms such the National Curriculum, more rigorous school inspection regimes and increased secondary school diversity. Consequently successive Labour Governments accepted much of the above mentioned neo-liberal rationale for the development of a quasi market in education and Labour's 1997 General Election manifesto emphasised that Labour would abolish grammar schools only if a majority of eligible parents voted for their abolition and that reform of the Comprehensive system must involve a shift from mixed ability teaching to setting. Thus Labour's 1997 Manifesto stated "We must modernise comprehensive schools. Children are not all of the same ability, neither do they learn at the same speed. That means "setting" children in classes to maximise progress for the benefit of high fliers and slow learners alike. The focus must be on levelling up, not levelling down."

Furthermore private schools would be retained with governmental efforts to enhance their links with state schools and although Grant Maintained schools would be replaced by Foundation schools this did not amount to a very significant change in the overall structure of educational provision. Also City Technology Schools and Faith Schools would be retained, the Specialist School Programme would be much expanded and from 2002 the Labour Government embarked on its City Academy Programme , soon to be renamed as the Academies Programme.

Some critics of Labour's education policies have argued that Labour adopted an overall rhetoric which continued what Paul Trowler has called the "discourse of derision" applied to teachers and schools during the Conservative era and could be interpreted as suggesting a criticism of the fundamental principle of comprehensivisation and as undermining the best efforts of teachers working in the more "challenging" comprehensive schools. Thus Tony Blair's first Secretary of State for Education David Blunkett "named and shamed" 18 comprehensive schools deemed to be "failing"; Alistair Campbell [ himself a staunch supporter of comprehensivisation] publicised Tony Blair's choice and diversity agenda as signalling "the end of the bog standard comprehensive" while a subsequent Education Secretary Estelle Morris stated that although some comprehensives were very good there were others that she "would not touch with a barge pole".

Perhaps the most forceful supporter of the choice and diversity agenda was the Prime Minister's education adviser and subsequent Minister for Education Lord Andrew Adonis. In his recent book "Education: Education: Education" Lord Adonis has criticised the roles of some Local Education Authorities and the Teachers Unions in the development and implementation of education policy and claimed that in many cases little had been done to modernise many [but certainly not all] comprehensive schools which consequently , even at the beginning of the 21st Century, could be described as essentially "Secondary Modern Comprehensives." Thus , for Lord Adonis the choice and diversity agenda in general and the Academies Programme in particular represented an attempt not to undermine the comprehensive principle but to improve the effectiveness of the comprehensive schools through reform of their management structures and teaching methods. However many continue to argue that despite the arguments of Lord Adonis , the choice and diversity agenda does indeed undermine the comprehensive principle in a manner which is highly likely to result in increasing inequality of educational opportunity. Thus the criticisms of Conservative education policies which had been outlined by Ball, Bowe and Gerwitz might be seen to apply equally to Labour's Choice and Diversity agenda.

Click here for a recent Guardian article on extent to which parents are prepared to move house into catchment areas of popular schools. September 2015

Nevertheless despite the criticisms of the quasi-marketisation of education advanced by Ball, Bowe and Gerwitz [see above] and others this process accelerated under Labour governments [1997-2010] and under the current Coalition government [2010-15] both of which continued to claim that quasi-marketisation could drive up educational standards including the standards of the more disadvantaged pupils.

One of the most significant aspects of this process has been the Academies Programme which was introduced by the Labour Government in 2002 and accelerated significantly under the Coalition Government. A large number of studies of Labour's Academies programme have been undertaken although it is generally agreed that it is too soon to evaluate the effectiveness of new academies opened by the Coalition. Many of the Coalition's academies are converter academies which differ in important respects from the sponsored academies opened by Labour although a fairly large number of Coalition academies are also sponsored academies.

In Feb 2015 The House Of Commons Education Select Committee published its Report on Academies and Free Schools.

Click here for the full report on Academies and Free Schools and scroll to Section 2 pp 10-24 for the section on Academisation and Pupil Progress] The members of this committee have been advised by Professor Stephen Machin who has himself conducted important and highly respected research on the possible effects of academisation on pupil attainment some of which is summarised in my own summary document on Academies. The Committee concentrate their research primarily on the effects of sponsored academisation on pupil progress arguing that it is to soon too assess the effects of the Converter Academies. Their key conclusion is that "Current evidence does not allow us to draw firm conclusions on whether academies are a positive force for change. According to research we have seen, it is too early to judge whether academies raise standards overall or for disadvantaged children. This is partly a matter of timing. We should be cautious about reading across from evidence about pre-2010 academies to other academies established since then."

After the 2015 General Election: Towards Increased Selection?

The 2015 General Election saw the demise of the Coalition and the return ofa single party majority Conservative Government under PM David Cameron. It seemed likely that a process of compulsory academisation would be introduced but following opposition from local authorities, teachers' unions and MPs [including some Conservative MPs this proposal was abandoned. [Click here for details from Schools Week] .

Recent DFE data on numbers and attainment levels of different types of schools within the English state sector are presented in the following table.

Percentages of Students and GCSE Attainment in Different Types of School 2014/15 [England]

| Number | 5or more GCSE A*-C including English and Maths | EBacc %of pupils entered for all components | EBacc % of pupils achieving all components | |

| Comprehensive Schools | 2780 | 56.7 | 38.2 | 23.1 |

| Selective Schools | 163 | 96.7 | 77.3 | 69.7 |

| Secondary Modern Schools | 121 | 49.7 | 26.9 | 13.9 |

| All State Funded Mainstream Schools | 3069 | 58.1 | 39.4 | 24.7 |

In relation to this table the following points should also be noted.

- Although the official number of Secondary Modern schools stood at 121 in 2014/15? it can easily be argued that perhaps 600 secondary schools might be described as Secondary Moderns.

- Examination results of selective schools are predictably better than those of Comprehensive schools which, in turn are better than those of secondary modern schools.

- On the basis of May 2016 DFE data quoted by the BBC out of 3381 English State Secondary Schools 2075 such schools were academies.

- Using House of Commons data for September 2015 1172 Comprehensives[42%] were Converter Academies ; 139 Grammar Schools [85%] were Converter Academies and 76 Secondary Modern Schools[48%] were Converter Academies.

- There are significant socio-economic differences and differences in measured ability ranges in the intakes of different schools. Broadly speaking grammar school pupils are on average more likely to be drawn from middle class backgrounds and to have relatively higher measured abilities ; taken as whole total comprehensive schools contain pupils from a wide range of social backgrounds with a wide range of measured abilities but in some Comprehensives there are far heavier concentration sof middle class and high measured ability pupils than others which leads to considerable differences in the examination performances of different comprehensive schools; since secondary modern schools exist only where there are selective schools the average measured abilities of secondary modern pupils may be relatively low although of course measurement methods are far from perfect and so some secondary modern pupils and probably/possibly a large number actually have considerable academic potential.

Proposals to increase the number of Grammar Schools

Following The UK EU Referendum and the resignation of David Cameron the Conservatives elected Theresa May as new Conservative Prime Minister and Mrs May , supported by new Secretary of State Justine Greening indicated that she favoured an increase in the number of grammar schools, a policy which previous Prime Minister David Cameron had not supported. A Government consultation paper was quickly published in which the Government outlined its broad education plans and aimed to canvass opinion as to how these plans might best be implemented.

The publication of the Government consultation paper has understandably sparked intense interest ; many articles , some of which are statistically complex have already been published and the House Of Commons Select Committee on Education convened a meeting of expert education policy analysts to discuss these issues in detail on November 8th 2016.

Click here to access full video coverage of this meeting Also in any case the Government's precise plans will not be known for some time and so we can expect much more information on this topic in the near future.

In the meantime I shall end this document for the time being with a summary checklist of arguments which are currently being made for and against increasing the number of grammar schools. I shall update it gradually as more information becomes available .

Conclusion

Current Arguments For And Against Introduction Of More Grammar Schools: A Summary

|

|