Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Welcome to the revised 2023 version of this document. I can remember when in earlier versions a focus of attention may have been, say, Labour’s Education Action Zones or the Education Maintenance Allowance whereas now the main concern is with the Government’s response to the Covid 19 pandemic via the education recovery Programme.

My advice, for what it is worth, is that students might study use the initial discussion of the nature of Compensatory Education but then concentrate mostly on reading the final section of the notes on Conservative Government Policies from 2015 to 2023 and look back at earlier compensatory education policy initiatives of Labour and Coalition Governments as advised by their teachers. They might then make a summary of the information for examination purposes.

For a very useful You Tube podcast on Education Policy and Inequality by Ms. A. Sugden – Click Here

Document Contents

|

Introduction

Compensatory education policies are intended to offset the effects of socio-economic disadvantage which may restrict the educational opportunities of children from socially deprived backgrounds. In practice the policies focused originally upon the assumed cultural deprivation of black children in the USA [as in the Operation Head Start Programme] and working class children in the UK [as in the Education Priority Area Programme] and have consequently attracted criticism from sociologists who argued strenuously against the concept of cultural deprivation.

Conservative governments of 1979-1997 claimed that overall educational standards could best be improved via the extension of individual parental choice which would result indirectly in the expansion of effective schools and the contraction and possible closure of ineffective schools. The Conservatives claimed that via these mechanisms educational opportunities would be improved for children of all social backgrounds and that the EPA Programme could reasonably be phased out as it was in the mid 1980s.

It may perhaps be argued that later compensatory education policies introduced by Labour Governments between 1997 and 2010 such as Sure Start, Education Action Zones and Excellence in Cities Programmes, Educational Maintenance Allowances and the Aim Higher Scheme are based less upon the concept of cultural deprivation and more on improving pre-school facilities, improving the schools themselves and providing financial help and advice designed to give socially disadvantaged children a fairer chance to fulfil their ambitions. However despite these policies reductions in inequalities of educational attainment have been limited and indeed critics of Labour education policies have argued that Labour’s acceptance of New Right Education policies based around the expansion of the quasi -market in education actually served to increase inequality of educational opportunity.

Under the Coalition Government the Educational Maintenance Allowance and the Aim Higher Scheme have been replaced by alternatives and the Coalition has also introduced the Pupil Premium and modified and significantly extended the Academies Programme which had been introduced by the previous Labour Government in 2002. Free Schools have also been introduced.

I consider the compensatory Education policies of Conservative Governments 2015-2023 under the following headings:

- Overall Levels of Government Spending as operating via the National Funding Formula.

- The Effects of the Quasi- Marketisation of Education.

- Sure Start Centres

- The Pupil Premium

- Opportunity Areas, Education Investment Areas, and Priority Education Investment Areas.

- The Response to the Pandemic: Education recovery in schools in England

The Functions of Education Priority Areas

The 1967 Plowden Report entitled “Children in their Primary Schools” called for, among other things, “positive discrimination” which should “favour schools in neighbourhoods where children are most severely handicapped by home conditions” by targeting additional financial resources on the education of these children. This proposal was readily accepted by the then Labour Secretary of State for Education Tony Crosland and by one of his key education advisers A.H. Halsey who was to become national director of the EPA programme. [According to Crosland real equality of educational opportunity was impossible without positive discrimination because disadvantaged children would be unable to take advantage of the opportunities which schools were offering unless there were also positive discrimination in their favour. This is what Crosland described as the “strong version of equality of opportunity”, a version which he himself very much supported]

Educational Priority Areas were set up in the late 1960s in parts of London, Birmingham, Liverpool and the West Riding of Yorkshire and schools in the EPA areas were provided with additional financial resources designed to “raise the educational performance of children, improve the morale of teachers, increase the involvement of parents in their children’s’ education and to increase the “sense of responsibility” for their communities of the people living in them.” [Halsey 1972]. In particular there were to be new and refurbished school buildings, special courses for teachers in EPA schools, special higher pay scales to encourage teacher retention, more playschools and nursery classes, policies to improve home -school communication and integration of the EPA initiatives with the work of Health and Social Services departments in wider “Community Development Programmes”. Additionally social scientists involved in the EPA programmes hoped to use so-called action research strategies to test the effectiveness of the programmes in operation and to modify and refine the programmes after discussion with the officials, parents and teachers participating in the schemes.

Criticism of the Concept of Compensatory Education and of the Education Priority Area Programme

These policies seemed sensible and well meaning but the concept of compensatory education and the policies introduced in the Education Priority Areas soon generated considerable controversy within Sociology because of disputes surrounding the causes of poverty and of social class differences in educational achievement and related disputes as to how poverty and social class inequalities in educational achievement might best be reduced.

With regard to the broad causes of poverty sociologists distinguish between “cultural explanations” and structural explanations. Cultural explanations [as for example in Oscar Lewis’ theory of the culture of poverty] explain the causes of poverty mainly in the assumed cultural deprivation of the poor which is believed to involve family instability, fatalism and lack of ambition, unwillingness to participate in the institutions of the wider society and inappropriate socialisation of the young .However, contrastingly, in structural explanations of poverty it is argued that the causes of poverty derive from the unequal distributions of power, income, wealth and opportunity which are seen as an inevitable characteristic of the operation of capitalist economies.

There are also disputes surrounding the causes of social class differences in educational achievement. Such causes might include social class differences in intelligence [which may or may not be mainly genetically inherited], social class differences in attitudes and values which imply that working class families and their children are more likely to be culturally deprived, social class differences in culture which nevertheless imply class difference without working class cultural deprivation, social class differences in material circumstances and factors operative in the schools themselves which operate to the disadvantage of working class pupils.

More radical sociologists [often but not always influenced by Marxism] argued that programmes of compensatory education had been introduced by “liberal” politicians of the USA Democrat party and by social democratic politicians of the British Labour Party who had accepted cultural explanations of the causes of poverty and sought remedies for poverty which would involve little or no redistribution of power, wealth and income from rich to poor and no challenge whatsoever to the continued existence of capitalism which , in the radical view, was itself the fundamental cause of poverty. The radicals further claimed that programmes of compensatory education were based on an uncritical acceptance of the theory that social class differences in educational achievement were based primarily on the cultural deprivation of the working class. This same concept has been expressed also in terms of the “cultural deficit” believed to be experienced by many working class children or even in terms of the “cultural pathology” of the working class.

The educational theories based upon the concept of cultural deprivation are discussed in more detail elsewhere on the site as are the criticisms of them. Many sociologists were critical of the theories which explained social class differences in educational achievement in terms of the cultural deprivation of the working class and proposed that other explanations were far more significant. Thus ,for example, Bernstein lamented that his own linguistic theories were being used in support of the notion of cultural deprivation which was certainly not what he intended; Bourdieu’s theories suggested that working class children were culturally different but not culturally deprived and that they were likely to be unsuccessful in school because schools undervalued working class culture and assessed pupils in terms of a dominant culture possessed by the middle class but not the working class children; Keddie argued that the very concept of compensatory education itself actually encouraged the negative labelling of working class children as “culturally deprived”; and relative working class educational underachievement can be explained also in terms of disadvantaged material circumstances and /or inadequate school resources and inappropriate labelling processes operating inside schools.

For further information on differing explanations of social class differences in educational achievement and click here for more details on theories of working class cultural deprivation and criticisms of them.

In summary critics of USA and UK programmes of compensatory education argued in the 1960s and 1970s that they were based on a misunderstanding of the causes of poverty and of relative working class educational achievement which meant that such policies would inevitably be ineffective as argued most forcefully by Bernstein in his article “Schools cannot compensate for society”.

A. H. Halsey’s Rejoinder

These are powerful criticisms of strategies of compensatory education but it could be that as criticisms of the theoretical foundations of the EPA Programme they may not be entirely justified. Thus , in a 1974 article A.H. Halsey emphasised the importance of both structural and cultural factors in the explanation of poverty, the necessity of more effective teacher training, better teaching greater efforts by schools to reach out to poorer parents and national policies to maintain employment and reduce poverty as well as policies designed to improve parenting skills .Halsey had therefore recognised all of the points made by his radical critics but believed nevertheless that compensatory education implemented through the EPA programme could play some part in the reduction of poverty and educational inequality but that it would need to be accompanied by broader , structural reforms organised at the national level.

Perhaps it is fair to say, however, that Professor Halsey was over-optimistic. The Plowden Report had originally recommended that 10%[3000] primary schools should be given EPA status but only 130 schools were so designated and the quality of the programmes introduced varied significantly from area to area. Also more poverty and educational disadvantage existed outside the EPA areas than inside them and since coherent national strategies to reduce poverty and social class inequalities in educational achievement were not enacted in the EPA era, the EPA policies alone could be expected to have at best only a limited impact on overall poverty and educational disadvantage. However writing in 1980, Halsey continued to argue that “Education can Compensate” and many would argue that he is correct in this view but only if meaningful nation-wide educational reforms are combined with wider social and economic reforms designed to reduce poverty and economic inequality.

The Conservatives and Compensatory Education 1979 -97

Conservative governments of 1979-1997 claimed that overall educational standards could best be improved via the extension of individual parental choice which would result indirectly in the expansion of effective schools and the contraction and possible closure of ineffective schools. The Conservatives claimed that via these mechanisms educational opportunities would be improved for children of all social backgrounds and that the EPA Programme could be reasonably phased out as it was in the mid-1980s.

However, critics of overall Conservative policies have argued the growth of inequality and poverty in the 1980s will have adversely affected the educational prospects of more disadvantaged pupils and researchers such as Ball. Bowe and Gerwitz suggested that the quasi- marketisation of education was most likely to benefit the children of affluent parents to such an extent the direct compensatory measures introduced by the Coalition and Conservative Governments such as the Pupil Premium and the National Tutoring Programme were unlikely to redress the balance.

Labour and Compensatory Education 1997- 2010

Since 1997 successive Labour governments introduced a range of education policies including the expansion of the Specialised Schools programme, the setting up of the Academies Programme and support for Faith Schools all of which were aimed at increasing choice and diversity and raising overall education standards. However as mentioned above critics have suggested that the “Choice and Diversity” educational agenda introduced by the Conservatives and extended by successive Labour Governments may have contributed to increased inequality of educational opportunity as upper and middle class parents have been able to use their economic, social and cultural capital to secure their children’s entry to the most effective schools. However, Labour supporters of the “Choice and Diversity” educational agenda have argued that it too can help to improve educational opportunity for disadvantaged children.

Labour also introduced additional policies involving elements of compensatory education designed to improve educational opportunities for disadvantaged students. These policies included especially the Sure Start, Educational Action Zones and Excellence in Cities Programmes, the Education Maintenance Allowance, and the Aim Higher Initiative.

Via the Sure Start Programme Labour tried to address the difficulties faced by poor parents in providing pre-school educational activities for their children while via the Education Action Zones and Excellence in Cities programmes Labour tried to address some of the alleged deficiencies of schools in deprived areas. In broad terms it has been argued that the Sure Start Programme has improved overall pre-school educational opportunities but that it has been difficult to reach the most deprived parents and children who have most to gain from the Programme and that the Education Action Zones and Excellence in Cities Programmes may have improved overall education standards only to a limited extent and, again, that the schemes have provided only limited educational benefits for the most disadvantaged children .

A report from the then DCFS [now DfE] indicated that differences in educational achievement between pupils eligible for Free School Meals and pupils ineligible for free school meals narrowed slightly and that the rate of examination result improvement in schools with high proportions of Free School Meals students was increasing relative quickly but critics have claimed that Labour’s compensatory education programmes have did relatively little to alleviate class disadvantage within the education system and that much more would need to be to be done if real progress is to be made on equality of educational opportunity.

Further Information on Labour’s Compensatory Education Policies

Further detailed information on the Sure Start, Education Action Zones, Excellence in Cities, Educational Maintenance Allowance and Aim Higher programmes is provided below. [However, this information is now slightly dated, and students should consult their teachers for advice as to how much detailed information about these various initiatives required for examination purposes and make examination summaries as appropriate.]

It has often been suggested that the Sure Start Programme has been influenced at least to some extent by the organisation of the Operation Headstart Programme which had been introduced in the USA in 1965 as an attempt at early intervention to promote the development of disadvantaged children via the encouragement of better parenting techniques. The first Sure Start centres were set up in 1998 and concentrated in areas of severe social deprivation. They were designed to provide facilities in deprived areas for childcare, early education, health and family support services and employment advice for families with children under 5 with the aim of reducing child poverty and social exclusion. Between 2006 and 2008 additional centres were set up in less disadvantaged areas while by 2010 the aim was to provide a total of 3500 Sure Start Centres to reach all children under 5 in all areas of the country.

The original overall rationale for the Sure Start Programme was based upon the general idea that parents in deprived areas might well be very keen to do the best for their children but that their lack of knowledge and parenting skills might put their children at a considerable educational disadvantage even before they entered school which would would then restrict their future educational progress throughout their school careers. Recent support for the rationale behind the Sure Start Scheme is provided in several studies which suggest that many children from economically deprived backgrounds enter First Schools at a considerable disadvantage relative to middle class children.

For example the necessity for some forms of assistance for children in disadvantaged families has been emphasised in the research of Professor Feinstein who has shown that social class disadvantages tend to affect the intellectual progress of poorer children even before they enter First School and in more recent research from the Sutton Trust.

Click here for information on Professor Feinstein’s research findings and for the BBC coverage of the recent Sutton Trust Research – Click Here

For a BBC item on the Sure Start Scheme suggesting its benefits may be limited – Click Here

For recent [July 2011] BBC Radio 4 Analysis Programme on Sure Start – Click Here

For a Guardian article outlining the history of the Sure Start Programme to 2011 – Click Here

Sure Start and the Coalition Government 2010-15.

There have been controversies surrounding the development of the Sure Start Programme under the Coalition government. Critics have claimed that several hundred Sure Start centres have been closed while the Government has argued that the decline in the number of Sure Start centres has arisen primarily [but not entirely] as a result of amalgamations of smaller centres.

For recent information on Sure Start closures Click Here and Here [Thanks to Fran Nantongwe for drawing my attention to these articles.]

Research on the Sure Start Programme from The Institute for Fiscal Studies 2024

In April 2024 the Institute for fiscal Studies published a very detailed report on the long term effectives of the Sure Start Programme which was given widespread coverage in the media. The Report concluded that the Sure Start Programme had been much more effective than was previously thought. Thus, the Report compares the outcomes of pupils who lived near Sure Start Centres and therefore potentially had access to them with the outcomes of pupils who did not and concludes that pupils living near the centres performed up to three GCSE grades better than those living further away. The researchers also estimate that the benefits of using Sure Start Centres may have been as much as three times as large as the average impact on all children in the area but that there is some uncertainty in these estimates due to data limitations.

Notice also that perhaps unsurprisingly there are political disputes as to the effective of the Sure Start Programme relative to the support systems that are currently available [as indicated in the BBC coverage of the IFS research .]

Click here and Here and here for IFS Research on the Sure Start Programme. The Report is technically complex, but students may find the 2 page Executive Summary with key findings useful

Click here for BBC coverage and here and here for Guardian coverage of the IFS Sure Start research

Education Action Zones[ EAZs}

- Under the terms of the Education Action Zones programme launched in 1998 Education Action Zones were to be designated in deprived areas in which new Forums involving parents, teachers, LEA members and business and voluntary association leaders who would devise strategies for the improvement of under-performing schools in the Zone.

- 12 large EAZs were designated in 1998 followed by a further 13 in 1999 and by 2002 there were 73 large EAZs containing 1444 schools serving around 6% of the English school pupil population.

- Each large EAZ contained one or two secondary schools together with their feeder primary schools amounting to around 20 schools in each large EAZ.

- Large EAZs were to receive £500,000 p.a. of DfES unconditional funding and it was hoped that they would also raise a maximum of £250,000 p.a. in private sponsorship which would be matched by additional conditional DfES [now DCFS] funding of up to £250,000 p.a. The large EAZs were therefore expected to receive a maximum of £1M p.a. in additional funding.

- Smaller EAZs were also created based upon single secondary schools and their feeder primary schools and these were to receive £250,000 p.a. in unconditional DfES funding,. They were also expected to raise up to £50,000 per. a. from private sponsorship which would be matched by further funding from the DfES.

- It was hoped that the EAZ programme would harness local initiative and business dynamism which would facilitate improvements in school standards.

- Schools in the EAZs would be permitted to disapply the requirements of the National Curriculum in order to concentrate on the improvement of literacy and numeracy if the Forum considered this to be necessary.

- Schools in the EAZs were permitted also to ignore national teacher salaries agreements and to pay higher salaries in order to attract and retain good staff

However it soon became clear that the EAZs might face difficulties which the Labour Government had not envisaged. It has been argued that the dynamising effect of business involvement in the EAZs was limited because in some especially deprived areas few schools opted to join the EAZ programme because of the difficulties envisaged in raising private sponsorship; because even when financial sponsorship was forthcoming it was far more limited in amount than the government had hoped [and often in the form of gifts in kind rather than cash]; and because the actual input of business expertise into the programme was also far less than had been hoped.. The following links provide further information on the limitations of the EAZ Programme.

The Government announced in 2001 that the EAZ Programme would be discontinued and that the EAZs which were considered to have been successful would be incorporated into the Excellence in Cities Programme.

The Excellence in Cities Programme

The Excellence in Cities Programme began in 1999 and was targeted specifically on secondary schools containing disproportionate numbers of disadvantaged pupils in Inner London, Birmingham, Manchester/Salford, Liverpool/Knowsely and Leeds/Bradford. Initially the scheme involved 23 LEAS, more than 400 secondary schools and central government expenditure of £24M p.a. central government spending but reached £ 386M p.a. by 2005/6 and the coverage of the scheme was extended to 58 LEAS containing approximately 1/3 of English secondary schools. The scheme was extended to cover many primary schools and so-called EiC clusters and works in conjunction with newer schemes such as the Leadership Initiative Grant and the Behaviour Improvement scheme .In any evaluation of the scheme however, it should be noted that in 2000/1LEAs current Secondary school spending was around £6B p.a. so that EiC spending was a relatively small proportion of total LEA secondary school spending

I shall attempt to describe only the broad features of EiC scheme as it has applied in secondary schools. In EiC- designated areas Local Education Authorities and their secondary schools enter into partnerships designed to improve Secondary School performance using an agreed EiC strategy framework involving the following strands.

- The expansion of Specialist and Beacon schools [which attract increased government funding] is encouraged in the EiC areas and it is hoped that best educational practice will radiate out from the Specialist and Beacon schools to reach all other schools in the EiC Programme;

- Individual schools appoint learning mentors who aim to encourage relatively disaffected pupils to participate more actively in their education.

- Individual schools try to recognise their Gifted and Talented pupils and to provide additional opportunities for them to develop their talents.

- Learning Support Units are set up to provide for the education of children who are having difficulties in mainstream schools in the hope that with guidance they will be able to return relatively quickly to the mainstream.

- City Learning Centres are set up with extended opening hours and good IT facilities designed to serve both school-age pupils and the local community as a whole

- Education Action Zones are incorporated into the EiC Programme.

However research findings on the effectiveness of the scheme have been a little contradictory. In 2005 a NFER Report on the effectiveness of the scheme between 1999-2003 concluded that at Key Stage 3 there was some evidence that EiC pupils performed better in Mathematics in comparison with non-EiC pupils of similar abilities and social characteristics but that the EiC scheme had had no noticeable positive effects on performance in Key Stage 3 Science and English examinations . Neither had the scheme improved the overall GCSE results of EiC pupils in comparison with non EiC pupils of similar abilities and social characteristics. These particular conclusions of the NFER Report were of course the ones which attracted mass media headlines but the Report noted also that there was some evidence that the overall atmosphere in EiC schools was improving , that it was possible that the EiC scheme had not been in operation long enough to have a positive impact on examination results and that in any case further preparatory work was necessary in Primary schools if newly arriving Secondary school pupils were to benefit from the EiC initiatives.

Government Education Ministers argued in response to NFER findings that since they referred only to 1999-2003, they were already out of date by the time they were published and failed to take account of most recent government initiatives and the Government arguments were supported to some extent by the findings of a 2005 OFSTED Report which concluded that the effects of EiC schemes were variable depending especially upon the quality of the Head teachers and other senior staff involved in the schemes but that they had on average narrowed the performance gap at GCSE level between EiC schools and the national average attainment of 5 or more A*-C GCSE grades from 10.4% to 7.8% between and 2001-2004.

The Excellence in Cities Programme was discontinued in 2006 and another report on the Excellence in Cities Programme was published in 2007 by researchers at the London School of Economics and the Institute of Fiscal Studies. They focused especially on attainments at Key Stage 3 and on rates of school attendance and concluded that there had been positive effects on pupil achievement in Mathematics but not in English and that the effects of the EiC programme varied considerably : effects were more positive the longer the policy had been in place; stronger for disadvantaged schools but stronger also for medium to high ability pupils within disadvantaged schools. Unfortunately also the researchers concluded that it had proved difficult to improve the attainments of lower ability pupils within the disadvantaged schools.

For a summary of LSE/IFS Research – Click Here

Every Child Matters

For a detailed report on Labour’s Record on Education: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 1997-2010 – Click Here

Both of these sources provide a concise outline of the Every Child Matters Programme and these Guardian items on Every Child Matters provide some examples of the beneficial effects of the Programme.

For a video on examples of ECM initiatives – Click Here

The implementation of the Every Child Matters initiative signaled a clear recognition that there is more to education than simply attainment of good examination results; that schools have an important role to play in fostering the wider well being of their pupils; and that better inter-agency coordination is necessary to improve the life chances of at risk children. As mentioned the above Guardian items points to some successes of the Every Child Matters initiative but the tragic death of Baby P and the discovery of widespread sexual grooming of children in Rotherham points to the continued existence of extreme dangers for some children while the continued existence of entrenched social inequalities may mean the the ECM programme in isolation may be insufficient to address the difficulties that many disadvantaged children face.

- For a detailed report on Labour’s Record on Education: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 1997-2010 – Click Here

- I shall not pursue further the various detailed evaluations of the EAZ , EiC and Every Child Matters Programmes but it does seem reasonable to conclude that ,although well intentioned, they have had a positive but relatively limited impact on patterns of inequality of educational opportunity and ,as has already been suggested above, further educational reforms combined with broader social and economic reforms are clearly necessary if equality of educational opportunity is to become a present reality rather than an unrealistic hope for the future.

For overall data on the overall effects of Labour Education Policies on patterns of educational attainment you may again Click Here for the already mentioned detailed report.

It has been noted that under the Coalition Government the term “Every Child Matters” is rarely if ever mentioned but the Coalition Government has nevertheless clamed that it continues to address the issues raised by the ECM initiative but in a different way. I shall try to provide some information on this aspect of the topic in the near future.

Extended Schools

The development of the Extended Schools programme evolved out of proposals for urban regeneration in the 1990s and gathere pace especially as a result of the Every Child Matters Programme introduced in 2004 which emphasised the need to support the full development of each individual child as well as the importance of multi-agency cooperation to promote this objective. In 2005 the then DfES published a programme which committed all schools to proving a core of extended provision. Thus by 201 all schools would be expected to provide:

- Before and after school child care and holiday play facilities;

- Homework clubs and additional classes targeted at disadvantaged children;

- Sporting and cultural enrichment activities for children;

- Targeted school support services for children such as counselling to support behaviour management or avoiding obesity.

- Support services for parents such as parenting classes band advice on health issues and activities and clubs for the wider community.

These services have generally been popular with children and parents and there is evidence that disadvantaged pupils have benefited from the services. However there have also been concerns that central government funding of the Programme has been insufficient thus necessitating charges for some of the services which poorer parents are less able to afford so that affluent children benefit disproportionately from the Programme.

It has also been noted that although the Coalition Government in 2010-11 did increase the government finances potentially available for the Programme it did also end the ring-fencing of the programme which meant that at a time of tightening overall education budgets finances potentially available for Extension activities were likely to be diverted to other areas of school budgets.

Nevertheless a recent detailed review of the Extended Schools Programme [see below] suggests that it certainly does have the potential to improve the life chances of all pupils including disadvantaged pupils and recommends that governments give the Programme increased priority in the future. The Following links provide some additional information.

For Guardian summary of report on Extended schools 2016 – Click Here

For Guardian on Extended Schools 2009 – Click Here

Every Child a Reader: Every Child Counts: Every Child a Writer

It seems clear that such schemes have the potential to improve the numeracy and literacy skills of pupils who are falling behind and a series of detailed reports suggest that the schemes have had some success in this respect. I shall not pursue this topic in any further detail here but further information can be found Here for links to detailed reports on the Every Child a Reader scheme. It remains abundantly clear that further initiatives are necessary if all children are to leave primary school reading well as is indicated.

- From Labour Government to Coalition Government

For a detailed Report on The Coalition’s Record on Education: Policy, Spending and Outcomes 2010-2015 – Click Here

For a summary of the report – Click Here

Key educational policies of the Coalition Government included the following.

- A major expansion of the Academies Programme

- Introduction of the Free Schools Programme

- Introduction of the Pupil Premium

- Continuation of the Sure Start Programme but with some criticism that under the Coalition the scope of the Sure Start programme was reduced.

- Discontinuation of the Education Maintenance Allowance, the Aim Higher Programme, and the One to One Programme along with government statements that the objectives of these programmes could be achieved by other means.

- A significant increase in Higher Education tuition fees,

The Academies Programme

The Academies Programme [ initially called the City Academies Programme but soon extended to deprived suburban and rural areas and renamed as “The Academies Programme] was initiated by the Labour Government in 2002 when the first three Academies were opened. The programme expanded steadily, and 203 Academies were open by 2010. These new Academies were State Secondary schools and usually replaced schools deemed to be “failing” and located in areas of social deprivation. They operated with sponsors which could oversee the development of the Academies independently of local education authority control although between 2002 and 2010 there would be some variation in the conditions attached to sponsorship and Local Authorities would themselves be permitted to co-sponsor Academies.

Under the Coalition Government the Academies Programme has changed significantly and been extended rapidly. Labour’s Sponsored Academies were, as stated, above, schools which were deemed to be “failing” and the Coalition has introduced several similarly sponsored Academies but has also introduced so-called “Converter Academies” which are high performing schools which are now permitted to operate independently of their Local Education Authorities but without external sponsorship and they are permitted also to themselves to sponsor schools deemed less effective in OFSTED inspections. The Coalition is also actively extending the Academies Programme to the Primary sector of education and the Coalition’s Free Schools and Studio Schools are also organised as Academies.

There has been considerable controversy surrounding the advantages and disadvantages of Academies related primarily to the debate around the desirability or otherwise of the further development of the quasi-market in education. Supporters of Quasi-marketisation of education in general and of academies in particular argue that the resultant competition between schools will lead to increased school efficiency which will result in improved educational attainment for all pupils including disadvantaged pupils so that the Academies Programme can be seen to contain elements of compensatory education. Critics of the system argued that it would enable more affluent parents to use their economic, cultural, and social capital to secure entry for their children to more effective schools at the expense of more disadvantaged pupils thereby increasing inequality of educational opportunity.

As part of this debate the examination results of Academies have been scrutinised in detail in attempts to draw meaningful comparisons between the results of Academies and all other State non-Academies and/or those State non-Academies with characteristics deemed similar to State Academies. In a 2015 Select Committee Report the members of this committee were advised by Professor Stephen Machin who has himself conducted important and highly respected research on the possible effects of academisation on pupil attainment some of which is summarised in my own summary document on Academies. The Committee concentrated their research primarily on the effects of sponsored academisation on pupil progress arguing that it was too soon to assess the effects of the Converter Academies.

Their key conclusion is that “Current evidence does not allow us to draw firm conclusions on whether academies are a positive force for change. According to research we have seen, it is too early to judge whether academies raise standards overall or for disadvantaged children. This is partly a matter of timing. We should be cautious about reading across from evidence about pre-2010 academies to other academies established since then.”

With regard to the Sponsored Academies and attainment the main points included in the Report include the following.

- There is evidence that rates of improvement in GCSE pass rates [5 or more A*-C GCSE pass rates] have been faster in sponsored academies. For an example article from the Conversation by Andrew Eyles and Steve Machin [2015] – Click Here

- However given that attainment levels in sponsored academies started from a lower level some narrowing of the attainment gap between sponsored academies and non –academies was to be expected.

- It is also important to note that despite some relative improvement attainment levels in sponsored academies have remained below the average national level although this is entirely predictable given that the original sponsored academies were set up in areas of relative social deprivation

- In any case there as significant differences in attainment levels as between individual academies and between academy chains. The ARK and Harris chains have been especially successful but others have not.

- here is evidence that although the main benefit of academisation is said to be increased individual school autonomy many academies are not actually modifying school practices very significantly.

- Insofar as attainment levels in sponsored academies are improving more rapidly this may be due to the fact that academy students have been entered disproportionately for “GCSE Equivalent” courses rather than actual GCSE courses. Attainment levels in sponsored academies tend to be much lower when only GCSE courses are considered.

- Although the DfE argue that the rate of improvement in GCSE pass rates of pupils eligible for free school meals is faster in sponsored academies than in comparable non –academies this has been disputed by other analysts such as Henry Stewart.

- It has been argued, most notably by O. Silva and S. Machin, that sponsored academies have done little to improve the attainment levels of pupils considered to be in the lowest 20% of the ability range.

- There is evidence of strong improvement in non-academies suggesting that academisation is certainly not the only route to school progress.

- There are claims that high quality leadership, high quality teaching and sufficient capital resources are more important determinants of pupil progress.

As mentioned, the expansion of the Academies Government under the Coalition Government involved the expansion of Converter Academies as well as Sponsored Academies and this would continue under the Conservative Government from 2015.The debate about academies continues to ebb and flow and you may find more recent and more detailed information on Academies here. Click Here to visit the Accadamies Progtamme

- Free Schools

- The setting up of Free Schools was proposed in the Conservative Manifesto of 2010 and given approval in the Academies Act of 2010 which also paved the way for existing state primary and secondary schools to become Academies. Free Schools are established as Academies independent of Local Authorities and with increased control of their curriculum, teachers’ pay and conditions and the length of the school day and terms. They may be set up by groups of parents, teachers, businesses, universities, trusts, and religious and voluntary groups but are funded by central government. Note also that several Free Schools have been set up by chains which already run several Academies and that some Free Schools have transferred from the Private to the State sector.

As of March 2015 there were 408 Free Schools open and David Cameron announced that if re-elected the Conservatives hoped to open a further 500 Free Schools by 2020 For a BBC item from March 2015 – Click Here.

In the event the years since 2015 have seen considerable political volatility but under successive Conservative Governments the number of Free Schools has gradually increased. Click here for more information on Free Schools.

The Pupil Premium

- The Pupil Premium included in the Liberal Democrats’ 2010 General Election Manifesto and introduced by the Conservative Liberal Democrat Coalition in 2011. The original rate was £ 488 per pupil but the rate has been increased substantially since then. In 2014-15 and 2015-16 annual Pupil Premium rates have been set at £1300 and £ 1320 for Primary age pupils and £935 ad £ 935 for Secondary age pupils

- Also, in 2011 the Education Endowment Foundation was set up as an independent charity with a founding grant from the DfE of £125 million. It has subsequently undertaken research into school’s use of the Pupil Premium and based on that research has produced various resources designed to improve the effectiveness of the Pupil Premium.

- In principle this additional funding should have helped disadvantaged pupils but in the early years of the Pupil Premium there were some concerns that in practice the money was not being used effectively.

- It was claimed that any increase in overall school finances provided via the Pupil Premium will to some extent be offset by the effects of reductions in funding elsewhere in the school budget.

- Furthermore it was suggested that although many schools were using the monies provided via the Pupil premium to target additional resources on disadvantaged pupils a sizeable percentage of schools are were doing so .For two items from the BBC – Click Here and Here

For a very useful Independent article suggesting that the Coalition are very committed to improve the effectiveness of the Pupil premium – Click Here

For a Guardian article [July 2nd 2013] indicating that Ofsted is intending to increase its scrutiny of schools’ use of pupil premium funds and that it is unlikely to issue “outstanding” ratings to schools with a wide attainment gap.– Click Here

For additional information from the BBC on the Pupil Premium – Click Here and Here

For Guardian coverage of a Demos assessment which indicated that in 66 out of 152 local authority areas investigated the attainment gap was now greater in 2013 than it was before the pupil premium was introduced. – Click Here

Addition 2023

We may use more recent data to look back at trends in the Deprivation Index in the Early stages of the Pupil Premium.

Click here and open the document and scroll down to Disadvantaged pupils and the disadvantage gap index of alternatively click here to access the relevant data directly. The calculation of this index is a little complex, but it is a measure of the difference between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils in average grades in GCSE English and Mathematics results. The disadvantage gap is shown to have fallen between 2010/11 and 2018/19 but has predictably risen again in the years of the pandemic.

Thus, in the early years of the Pupil Premium [2011-2015], there was a slight reduction in the disadvantage gap index, but we cannot assess the extent to which this reduction was caused by the pupil premium. Also this reduction in the disadvantage gap index was indeed very small: Click Here for a BBC item on Poverty and League Tables [ January 2019] which suggests that although the disadvantage gap at GCSE Level has been narrowing , if the current rate of closure of the gap continues poorer pupils will not catch up with their peers until the 2090 's.l

Both Conservative and especially Liberal Democratic spokespersons argue that the Pupil Premium should improve the educational opportunities of the poor and promote upward social mobility. Given the scale of the educational disadvantages faced by many such pupils many analysts argue that any improvement in equality of educational opportunity will be decidedly limited. We can certainly hope but should not expect too much.

The Sure Start Programme 1998- 2023

Update 2023.

The main issue in the years of the Coalition Government concerned the controversy surrounding the closure of many Sure Start Centres and whether as critics claimed this amounted to a diminution of services or whether as the Coalition claimed, levels of service were maintained but now delivered by other means.

The Sure Start Programme was introduced by the Labour Government in 1998. It envisaged a network of child centres which would provide information on parent6ing, health, school readiness and local employment opportunities. The programme was to some extent based upon the Operation HeadStart programme which had been introduced in the USA in the 1960s but although the limitations of that Programme were by now well recognised, the Sure Start programme was allowed to expand rapidly without detailed evaluation in the early years.

Click here for a short video of a Sure Start Centre in operation.

When detailed evaluations were published after several years, they showed improved parenting skills and more harmonious family life but no significant effects on the school readiness of children. However Sure Start Centres were very popular with parents, and it was also argued that although in the aggregate children’s school readiness had not improved, it had done so in the more effective Sure Start Centres and that it was therefore necessary to uncover the reasons for success and to replicate good practice to all centres. It was also pointed out that free childcare had recently been rolled out to all children and that this would have limited the catch-up possibilities for children attending the Sure Start Centre.

By 2010 there were approximately 3.600 Centres in operation, and it was widely believed that even if evaluation studies pointed to limited positive effects on school readiness, the Sure Start Centres did have considerable potential to improve school readiness in the future.

Click here for BBC Radio 4 Analysis from 2010 on Sure Start Centres and here for BBC News summary coverage of the conclusions from BBC Radio 4 Analysis.

Click here for Download of PDF Document Sure Start 2017 which summarises some of the conclusions of evaluations of the Sure Start Programme and of the evolution of Sure Start policies under Coalition Government and the early years of the subsequent Conservative Government.

When the Conservative-Liberal Democrat replaced Labour in government in 2010 it stated that Sure Start Centres would be retained but that it was necessary to give local councils more control over children’s policies which might result in a more flexible approach resulting in the closure of some centres, the merger of others and the relocation of service provision from some Sure Start Centres to other local government agencies. Thus, when critics noted the decline in the number of Sure Start Centres, government spokespersons noted that the overall level of services had been maintained but was being provided by other means.

However, there were also serious concerns that in an era of economic austerity central government reductions in grants to local authorities meant was resulting in a reduction in the number of Sure Start Centres, a hollowing out in the services that Sure Start Centres were Providing and an overall reduction in the availability of services for children. These criticisms were voiced, for example by the Sutton Trust and the Action for Children Charity while a significant report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies showed that Sure Start Centres had provided very significant health benefits for children who used the centres. . Such health benefits could be expected to translate also into education benefit. The following links provide more information on these issues.

Click here for BBC coverage and here for Guardian coverage of Sure Start Centre closures

Click here for BBC coverage of Sutton Trust research on closure of Sure Start Centres

Click here for the IFS Report and here for Guardian coverage and here for BBC coverage of the Report

In their research paper entitled The Conservative Governments’ Record on Early Childhood from May 2015 to pre-Covid 2020: Policies, Spending and Outcomes December 2020], LSE academics Kitty Stewart and Mary Reader analyse the full range of Governments Children’s policies. The link will take to the full Report, to a summary and to a short podcast which is well worth watching. In the following two quotations from the Summary of the Report the authors make a generally critical assessment of Conservative children’s policies and note that the number of Sure Start centres fell by 570 between 2010 and 2019 and by 240 between 2015 and 2019.

“This report summarizes our full SPDO paper on the record of successive Conservative governments in relation to early childhood (children under five) from 2015 to the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. The paper points to a mixed record on policies for young children and their families: there was progress on improving childcare affordability, but little action on childcare quality, while Sure Start children’s centres continued to be squeezed and cash benefits were cut. Overall, spending on young children fell and became less progressive. By 2020 inequalities had widened in a range of early child outcomes.”

“A squeeze on Sure Start children’s centres. The number of Sure Start children’s centres continued to fall from 2015. There were 3050 children’s centres in 2019, 240 fewer than in 2015 and 570 fewer than in 2010. While in some cases, centres merged rather than closed entirely, the overall number masks reductions in services, opening hours and staff and a reliance on external funding. In some cases, centres were incorporated into packages of early help with a wider age range, 0-19 or even 0-25. Action for Children suggests that there was an 18% fall in the number of young children using children’s centres since 2014-15 and 2017-18, with larger falls in more deprived areas, despite closures being concentrated in more affluent areas. Centres have also moved towards greater separation between open-access and targeted services for disadvantaged children, posing risks for social cohesion”.

In 2021 the Conservative Government announced its intention to set up a network of family hubs in England which will be designed to improve access to necessary services for parents and young children. These might be seen as an attempt to offset some of the effects of the closure of Sure Start Centres under the Conservatives and Conservative Minister Andrea Leadsom has suggested that existing Sure Start Centres might in principle be merged into the new Family Hub system. However although this imitative has been welcomed in a recent [2021] House of Lords Report, the Report also called for “ early years spending to be “levelled up” after revealing £1.7bn a year funding cuts to Sure Start, youth and other family support services over the past decade had disproportionately affected children in the most deprived communities.

Research on the Sure Start Programme from The Institute for Fiscal Studies 2024

In April 2024 the Institute for fiscal Studies published a very detailed report on the long term effectives of the Sure Start Programme which was given widespread coverage in the media. The Report concluded that the Sure Start Programme had been much more effective than was previously thought. Thus, the Report compares the outcomes of pupils who lived near Sure Start Centres and therefore potentially had access to them with the outcomes of pupils who did not and concludes that pupils living near the centres performed up to three GCSE grades better than those living further away. The researchers also estimate that the benefits of using Sure Start Centres may have been as much as three times as large as the average impact on all children in the area but that there is some uncertainty in these estimates due to data limitations.

Notice also that perhaps unsurprisingly there are political disputes as to the effective of the Sure Start Programme relative to the support systems that are currently available [as indicated in the BBC coverage of the IFS research .]

Click here and Here and here for IFS Research on the Sure Start Programme. The Report is technically complex, but students may find the 2 page Executive Summary with key findings useful

Click here for BBC coverage and here and here for Guardian coverage of the IFS Sure Start research

- Education Maintenance Allowances

| Family Income | Weekly EMA |

| Up to £20,817 | £30 |

| £20,817- £25,521 | £20 |

| £25,522- £30,810 | £10 |

-

- Education Maintenance Allowances were first piloted in 1999 and introduced throughout the UK in 2004 in order to encourage young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to remain in education. There were made available to all 16 -19 year olds whose Household income is less than £30,810 p.a. and are following academic or vocational courses up to Level3 [AS and A2 levels or AVCEs], some LSC -funded courses and courses leading to apprenticeships. The rates of payment related to Family Income are shown below.

- By 2011 -12 about 650,000 students were receiving EMAs of between £10 and £30 per week.

- It is estimated that around a half of all 16 year olds are eligible for EMAs of at least £10 or more per week.

- Eligible pupils receive a weekly term -time allowance of £10, £20 or £30 depending upon the precise level of household income which is available for the two or possibly 3 year duration of their course so long as they fulfil the terms of their EMA contract which must be negotiated with their school, college or training provider and lays down conditions as to regular attendance and necessary progress.

- The award of an EMA does not result in the reduction in any other social security benefits for which households may be eligible.

- Successful students may also be eligible for additional financial bonuses and may continue to work part-time without losing their eligibility so long as they are meeting the terms of their contract.

- For more information on EMAs from The Guardian. How successful have they been.? Will they be phased out in the current economic climate.? – Click Here

- Update : Yes they will be phased out

The Conservatives had denied during the 2010 General Election Campaign that they would abolish the EMA but following the formation of the Coalition Government George Osborne announced in the 2010 Public Spending Review that the EMA would in fact be replaced by “more targeted support. The Government claimed that at £560 Million p.a. the scheme was expensive and that it was also wasteful because , according to research from the NFER 90% of students would continue their courses without the payment.

However controversy soon arose as critics claimed that the Government had misinterpreted the results of this NFER study , a conclusion supported by the main author of the study.

For BBC coverage of discussion of research surrounding the ending of the EMA – Click Here and Here

When the Government had announced that the EMA was to be scrapped it did announce that a targeted replacement scheme would be introduced but there were nevertheless fears that about 300,000 students would lose their EMAs midway through their courses ..

In March 2011 the Coalition Government announced that it would replace the EMA scheme [estimated cost £560M p.a.] with a new fund for low income earners [ estimated cost £160M p.a. ] and that £15 M of this £160M will be used to give 12,000 of the most disadvantaged 16-19 year olds bursaries of £1200 p.a. The rest of the funds would be added to the existing “learner support fund” [estimated cost £26M p.a.] which is given to schools, colleges and other learning providers to use at their discretion. The Government also announced details of the gradual phasing out of the EMA payments. [See BBC Q and A on EMA.] However for discussion of controversies which soon surrounded the successor scheme – Click Here

- Aim Higher and Subsequent Access Agreements

The Aim Higher Programme provides information and activities designed to encourage children to consider the benefits of Higher Education. It is geared especially toward children whose parents have not themselves undertaken Higher Education courses. For further information about the Aim Higher programme and you can then discuss its likely effectiveness with your teachers – Click Here

Update 2011: The Coalition announced that the Aim Higher Programme would close at the end of academic year 2010-2011 and that alternative policies would be introduced to encourage HE participation among pupils unlikely otherwise to enter HE.

For further information from the Guardian – Click Here

For information from the BBC – Click Here

For information from the Times Higher Educational Supplement – Click Here and Here

When the Coalition Government raised Higher Education tuition fees to a maximum of £ 9,00 per year it also stipulated that any Higher Education Institutions wishing to charge more than £6,000 per year must negotiate a detailed access agreement with OFFA [The Office for Fair Access] specifying how they intended to improve access for disadvantaged students.The Conservative Government has subsequently continued with this approach. For further information – Click Here and Here

One to One

Labour also introduced the One to One Scheme whereby some children [often from relatively disadvantaged social backgrounds] who are considered to be making limited progress in the classroom setting can be provided with individual tuition to help them to catch up. The the Coalition Government announced in 2010-11 that finances for the One to One Scheme would no longer be ring-fenced but that schools could continue to finance the scheme from within their overall School budget.

For BBC coverage of the Coalition announcement – Click Here

I am currently trying to find further information on the how the organisation of the scheme has changed under Coalition and Conservative Governments.

Higher Education Tuition Fees

[Although I concentrate here only on the question of tuition fees there are other very significant issues affecting the future of Higher education as is indicated in this Guardian article on the future of the Humanities in Higher Education]

In December 2010 the UK Parliament passed the Coalition legislation which provided for the increase in Higher Education tuition fees in English institutions to a maximum of £9000 p.a. with effect from September 2012 . The precise details of the tuition fees scheme are quite complex. For a Q and A on Tuition Fees and University Funding from the BBC for further detailed information – Click Here

Notice especially that the higher tuition fees would apply also to English students studying at all UK Higher Education Institutions but not to N. Irish , Scottish and Welsh students studying at N .Irish, Scottish and Welsh Higher Education institutions who would however pay the higher fees if they enrolled at English Higher Education institutions. Welsh students at English HE institutions would receive grants to cover the difference between English and Welsh tuition fees.

Students would receive loans to cover the costs of their tuition fees. They would also receive a combination of grants and loans to help to cover their maintenance cost where the relative size of the grants and loans would depend upon parental income. Also universities were to offer a mixture of fee waivers and bursaries to help to reduce the financial hardships experienced by relatively socially disadvantaged students. It was recognised, however, that combined maintenance grants and loans would not be sufficient to cover full maintenance costs which meant that many students would need to work to supplement their grants/loans and /or take out additional private loans.

Consequently assuming tuition fees of £9,000 p.a. and maintenance loans which varied between £5,500 p.a. and £3,575 p.a. students could well leave university with debts to the government of more than £40,000p.a. on which interest would be charged. Once new graduates were in paid employment they were to contribute 9% of any gross income above £21,000 p.a. toward repayment of their loan. Thus for example a new graduate earning £30,000 p.a. would contribute about £16 per week to loan repayment.

It was widely believed that as a result of the increase in tuition fees there would be a significant fall in entrance to higher education and that the decline would be especially large among disadvantaged students. In the event university entrance initially increased as many students opted not to take a gap year but to enter university as early as possible in order to avoid one year of higher tuition fees. After that the number of entrants did indeed decline but recovered and by 2015 exceeded the pre-fees increase entry levels. The rates of entry of students who had been eligible for free school meals actually increased faster than the rate of Non -FSM pupils but , unsurprisingly, there is still a substantial entry gap between students eligible and ineligible for free school meals especially in relation to entry into higher status universities. And even though entry rates have recovered it may be that in the absence of the higher tuition feees entry rates would have increased much more substantially. Click Here for further information on the effects of higher tuition fees

Compensatory Education and Conservative Governments 2015-2023

In their survey of The Conservatives’ Record on Compulsory Education: spending, policies, and outcomes in England: May 2015 to pre-COVID 2020 Ruth Lupton and Polina Obolenskaya state that policy developments in in the compulsory education sectors between 2015 and 2020 have broadly continued the direction of travel taken by the Coalition Government of 2010-2015. It can also be argued that Coalition education policies followed principles which had been espoused by Conservative Governments of 1997-2010 and accepted, albeit with some significant modifications by Labour administration of 1997-2010. However, the years since 2015 have witnessed the COVID pandemic and a cost of living crisis generated by long term of real wages coupled with the effects on prices of the Ukraine war and these factors have resulted indirectly in increasing educational difficulties for more disadvantaged students.

Comparable Outcomes and Recent Examination Results.

In recent years until 2020 annual overall pass rates and grade distributions at both GCSE Level and GCE Advanced Level have been relatively stable because the overall pass rates and grade boundaries have been manipulated to achieve comparable outcomes: that is to try to ensure that “if the cohort of students taking a qualification in any one year is of similar ability to their predecessors, then overall results should be comparable.” Thus, the distribution of A level grades in any one year will be very closely related the distribution of GCSE results two years previously although the distribution of A level grades can be modified slightly if expert examination scrutinisers believe that this is justified. However, the overall effects of the comparable outcomes procedure is that year on year variations in GCSE and GCE Advanced Level results are likely to be small. This procedure has been adopted to remove the possibility of pass rate and grade inflation.

However due to COVID and the cancellation of examinations in 2020 and 2021 these procedures were not adopted and as a result higher level GCE Advanced Level and GCSE grades both increased substantially. However, it was decided that examination results should fall back return to their pre-COVID levels and by 2023 this had almost occurred In England although the reversion of examination results was slower in the rest of the UK. {You may click here for an explanation of comparable outcomes from Schools Week 2015 and click here for a detailed OFQUAL publication from 2020 and here Schools Week coverage for an interesting dispute as to when Comparable Outcomes were first introduced]

The implication is that examination trends must be interpreted with care. For example, using the IFS data via the first link below we see that GCSE pass rates rose faster between 2006 -2010 than between 2010 and 2015 and pass rates actually fell between 2012 and 2015 but this may have been due to processes of grade inflation and subsequent grade deflation rather than due to changes in the effectiveness of schools. After 2015 the key metric changed from 5 or more GCSE s grades A*-C to passes in GCSE English and Mathematics grades A*-C/9-4 and pass rates were very stable from 2015-2019 but this reflected the use of the comparable outcomes method and then in 2020 and 2021 there were no examinations and teacher assessed grades led to significant increases in grades which were reversed in 2022 and 2023.

My key conclusion is that national trends school effectiveness and the effectiveness of government education policies cannot be accurately assessed via the consideration of national examination results.

Some Data Sources on Examination Results

[ Discussion of inequalities of educational attainment is usually framed in terms of differences in educational attainment as between pupils eligible and ineligible for free school meals and I summarise some of the relevant data below. However, it is increasingly suggested that such data may provide a misleading picture of real trends in educational attainment gaps as is suggested here.]

Click here for a summary of a detailed IFS Report for data from IFS [2006-2019] which indicates that at GCSE level the GCSE results of FSM -eligible pupils have improved but that there has been little or no decline in the results gap between pupils eligible and ineligible for FSM. Also Click here for a Guardian article on this report and Click here and for the full IFS Report.

Click Here for a BBC item on Poverty and League Tables [ January 2019] which suggests that although the disadvantage gap at GCSE Level has been narrowing , if the current rate of closure of the gap continues poorer pupils will not catch up with their peers until the 2090s If the pace of change remains the same as it has been since 2011, poor pupils will not do as well until the 2090s.

Click here and open the document and scroll down to Disadvantaged pupils and the disadvantage gap index of alternatively click here to access the relevant data directly. The calculation of this index is a little complex, but it is a measure of the difference between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils in average grades in GCSE English and Mathematics results. The disadvantage gap is shown to have fallen between 2010/11 and 2018/19 but has predictably risen again in the years of the pandemic.

In 2023 Government spokespersons have claimed that the fall in the index to 2018/19 is testimony to the success of their education policies and that now that the pandemic is [hopefully!!] under control their policies will lead to further reductions in the disadvantage gap. However, critics of government policies have argued that the fall in the disadvantage gap has been painfully slow, that the quasi-marketisation may well have exacerbated educational inequality and that government education policies to mitigate the adverse educational consequences of COVID19 have been inadequate so that the slight reduction in the disadvantage Index which occurred in the years prior to COVID has now been reversed as indicted in this EPI Report [December 2022] and this very useful item from Schools Week..

A Level and other 16 to 18 results:

Click here for A level and other 16-18 results: 2022 [revised] and click here for excellent table on A Level and other 16-18 results of students eligible and not eligible for free school meals. There is an attainment gap of approximately one half of a grade per A Level subject. Click here for similar data on disadvantaged and non- disadvantaged students

Widening Participation in Higher Education

Click here for tables on Progression Rates to HE and here for Progression Rates to Higher Tariff HE. The data show that since 2010/11 increasing [percentages of FSM -eligible students have entered HE but that the FSM- Non FSM gap has increased for access to both overall HE and High Tariff HE.

In summary therefore the results of FSM eligible students themselves have improved but they have not improved relative to the results of non FSM pupils.

Examination Results: Conclusion

In the long term examination results at GCSE and GCSE have been improving and access to Higher Education has been increasing. Differences in attainment levels between pupils eligible and ineligible for free school meals have been narrowing very gradually prior to the Covid pandemic but the increase in attainment gaps after the pandemic have more than offset the narrowing of attainment gaps which occurred in the 10 years prior to the pandemic.

To assess the compensatory effects of government education policies on educational inequality of opportunity we may consider the following elements.

- Overall Levels of Government Spending as operating via the National Funding Formula.

- The Effects of the Quasi- Marketisation of Education.

- Sure Start Centres

- The Pupil Premium

- Opportunity Areas, Education Investment Areas, and Priority Education Investment Areas.

- The Response to the Pandemic: Education recovery in schools in England

Overall Levels of Government Spending as operating via the National Funding Formula.

[ The distribution of total government spending on education is progressive but less so in recent years which means that the extent to which the distribution of government spending compensates for educational disadvantage has declined. However considerable technicalities in this analysis and I should also mention that I have never seen these issues discussed in any GCE Advanced Level Sociology textbook which perhaps means that students do not need to spend much time on them.]

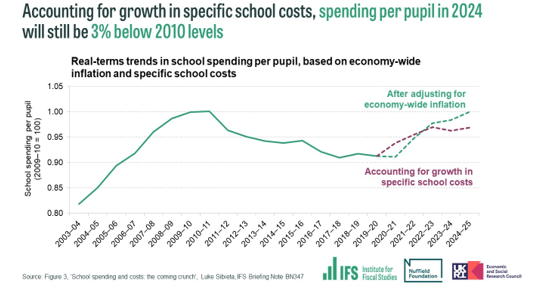

Analysis from August 2022 from the IFS indicates that once the recent specific cost pressures affecting the education system are taken account of real terms spending per pupil in 2024 will still be 3% below 2010 levels. Click here and here for IFS data and Click here for a Guardian summary

Update Autumn 2022

However, increases in school spending were announced in the Autumn Statement of 2022. The IFS analysis of these changes appears below.

School spending

The Chancellor announced an extra £2.3 billion in school funding in England for 2023-24 and 2024-25. This comprises an extra £2 billion compared with prior plans and £0.3 billion that no longer needs to be spent on the Health and Social Care Levy. This represents a 4% increase in school funding for 2023-24 and 2024-25.

This will allow school spending to return to at least 2010 levels in real terms. Based on economy-wide inflation captured by the GDP deflator, spending per pupil in 2024-25 will be about 3% above 2010 levels. If we adjust for an estimated index of school-specific costs, spending per pupil will return almost exactly back to 2010 levels. This means that school funding is now forecast to exceed growth in school costs, such as growth in teacher and support staff pay levels.

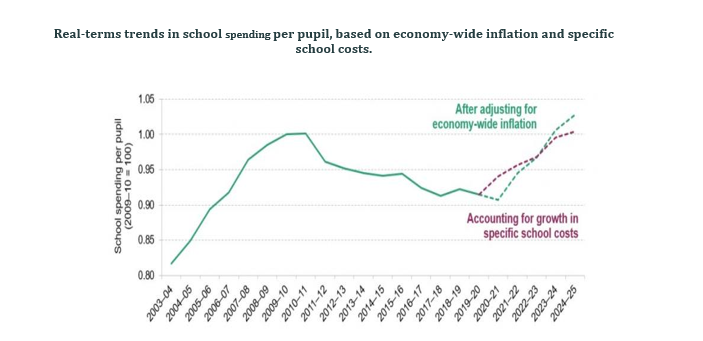

Real-terms trends in school spending per pupil, based on economy-wide inflation and specific school costs.

By contrast, other stages of education - like early years and further education - did not receive any uplift and so will be facing a significant squeeze from higher-than-expected inflation. Despite making much of the Education Secretary’s background in vocational education, the Chancellor has done nothing in this statement to reverse the long-standing squeeze on resources for further and adult education.

Click here for a Detailed IFS Paper from October 2022 and scroll to School Funding [pp85-109] and see especially pages 100-3

In this paper the National Funding Formula is explained in detail, and it is noted that deprived schools [as measured by the proportions of pupils eligible for free school meals] have traditionally been allocated greater funding such that in 2010-11, spending per pupil in the most deprived secondary schools was 34 % higher than in the least deprived secondary schools but that by 2019-20 this gap had fallen to 23%. In primary schools, the gap fell from 35% to 23%

There are some considerable technicalities involved in the analysis of these data and you may find some further analysis on page 24 of this paper. However, the basic conclusion stands that to some extent government spending policies over the last 10 years have reduced the overall progressivity of government education spending.]

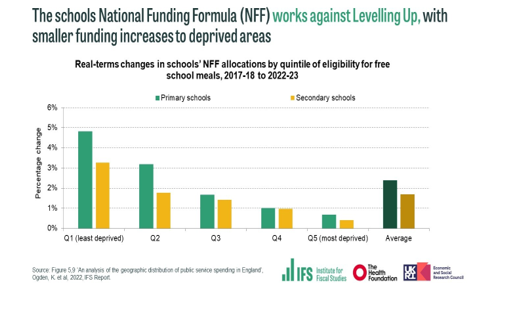

The following diagram then shows that, for primary and secondary schools, between 2017-18 and 2022-23, increases in school funding were skewed even more toward less deprived schools which means that although more deprived schools continue to receive larger funding than least deprived schools the extent of their funding advantage has continued to decline steadily. [ It is then noted that “the most deprived schools outside London have seen the largest spending cuts over the period [2010;11- 2019/20] with 15% real terms fall in spending per pupil amongst the most-deprived secondary schools outside London. This is naturally a concerning pattern given that these are the other areas with the lowest educational outcomes and potentially the highest extent of any “unmet need”.

The above chart indicates that as of October 2022 spending increases have been smaller for schools in most deprived areas than for schools in least deprived areas as measured by Free School Meal Eligibility

The Effects of the Quasi- Marketisation of Education.

Both the Academies Programme and the Free Schools Programme have expanded. Conservative spokespersons argue that expansion of these schools will improve overall school effectiveness which will improve the educational prospects of more disadvantaged students. Against this it is argued that differences in educational attainment between academies, free schools and local authority maintained schools are negligible and that if anything quasi-marketisation of education serves to increase educational inequality. You may click here for more detailed information on Academies and here for more information on Free Schools.

You may also click here and here for Ofqual 2023 examination results at GCE Advanced Level and GCSE Level respectively which show that differences in results among Academies, Free Schools and Local Authority Maintained Schools are fairly small.

Government spokespersons point out that OFSTED data indicate that the proportion of schools rated good or outstanding has increased from 68% 2010 to 88& currently and that this is testimony to the effectiveness of government education policies and can be assumed to improve the prospects of disadvantaged pupils. Against this, however, critics argue that most of the improvements in school rating arose because of changes in methods of Ofsted assessment and cannot be proven to derive from specific government education policies. You may click here for further information on Ofsted.

Critics argue also that the continued existence of Private schools and to a lesser extent grammar schools exacerbates educational inequality.

Sure Start Centres 1998-2023