Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Social Mobility and Education Policies

On September 30th 2020 I watched a video lecture by Professor Lee Elliot Major entitled Apocalypse or New Dawn: Social Mobility and Education post-Covid. I recommend it highly

Click here for Ruth Lupton article on Theresa May's social justice agenda

Click here and here and here for Theresa May and Social Mobility

Click here for Lee Eliot Major on Social Mobility and Education

The New Social Mobility (video lecture by Dr Geoff Payne).

Click here for Sutton Trust Report: Are the Elites pulling away?

Click here for LSE Blog post, here for the LSE event and here for BBC coverage of above report.

Click here for a Guardian article on Social Mobility by Lee Eliot Majors and Stephen Machin. These authors have also written Social Mobility and Its Enemies (Pelican), in which they argue that, for a variety of reasons, recent educational policies have been relatively ineffective in promoting social mobility.

Click here for a podcast discussion with Professors Stephen Machin and Lee Eliot Majors (Authors of Social Mobility and its Enemies).

Click here for The Social Mobility Trap (Tom Clark: Prospect).

Click here for The Problem with Social Mobility

Click here for latest report from the Social Mobility Commission on latest social mobility trends [June 2020]

Social Mobility rates may be defined generally as measures of individuals' movement within a society's class structure.

[A different approach to the measurement of mobility has been taken by JO Blanden. Paul Gregg and Stephen Machin who measured trends in income mobility and calculated that income mobility had slowed down in recent years, This conclusion attracted considerable political interest and you may click here for some further summary information on this research but I shall nevertheless concentrate on studies in which social mobility is measured via movement within the NS SEC social class rather than via movement between deciles of the income distribution]

The measurement of social mobility is technically complex. We may distinguish between various types of social mobility: upward and downward; intergenerational and intra-generational; long range and short range; and absolute and relative social mobility. [It is also important to analyse gender and ethnic differences in social mobility rates but I shall not do so here. ]

- Upward and downward social mobility refer to movements upward and downwards respectively in the class structure

- Intra-generational and inter-generational social mobility where the former is a measure of social mobility within a person’s own life time and the latter compares the class position of parents and children.

- Short range and long range social mobility where the former refers to mobility between similar occupational groupings and the latter refers to mobility between significantly different occupational groupings.

- Absolute and relative social mobility where the former assesses total social mobility rates and the latter measures the relative chances of people from different occupational groups of reaching higher and lower occupational groups respectively. Thus it may be that absolute social mobility from the working class to the service class is increasing but the chances that a working class child will end up in the service class may be far less than the chance that a service class child will end up in the service class.

With regard to the overall analysis of social mobility we may distinguish between differing sociological perspectives.

- Functionalist sociologists argue that social inequality is both inevitable because if derives from differences in natural abilities and talents and desirable because it provides the financial incentives for individuals to undertake long periods of training and to take up functionally important and therefore well paid jobs. Social inequality encourages individuals to work hard in order to achieve e financial success which will also increase overall rates of economic growth and improve living standards for all including the poorest success. . Functionalists argue also that modern societies will become increasingly meritocratic as it is recognised that increased social mobility will promote greater economic efficiency.

- Conversely Marxists argue that capitalist societies are inherently exploitative, unequal and unjust; that social inequality itself will inevitably inhibit upward social mobility; and that such social mobility as does occur will act as a safety valve which defuses opposition to the capitalist system and deprives the working class of talented potential opponents of capitalism.

- Especially since the 1970s great attention has been given to social mobility by neo-Weberian sociologists and in particular by John Goldthorpe and his associates. They focus upon the distinction between absolute and relative social mobility and conclude on this basis that there is little evidence that the UK has become increasingly meritocratic. Some additional information on John Goldthorpe's work is given below.

- The conclusions of John Goldthorpe have been challenged by New Right theorists such as Peter Saunders who argues that John Goldthorpe and his associates have wrongly downplayed the view that natural abilities are to a considerable extent genetically rather than environmentally determined and that once the effects of genetic inheritance are factored into the analysis the UK is shown to be much more meritocratic than John Goldthorpe and his associates have suggested. Click here for further information on Peter Saunders' view

- Of course many sociologists are critical of the New Right approach to social analysis

Absolute and Relative Social Mobility.

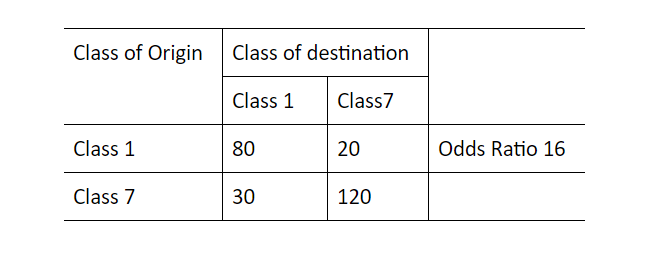

The distinction between absolute and relative social mobility can hopefully be clarified via the following numerical example.

Absolute Social Mobility is measured as a percentage of the whole population , which in my example is 250.

Absolute Downward Mobility from Class 1 to Class 7 is 20/250.

Absolute Upward Mobility from Class 7 to Class 1 is 30/250.

Therefore, Total Absolute Mobility is 50/250 = 20%.

Relative Social Mobility is measured by means of an Odds Ratio.

In my example this ratio is: [the chance that a Class 1 origin respondent will end up in Class 1/the chance that a Class 1 origin respondent will end up in Class 7] divided by [the chance that a Class 7 origin respondent will end up in Class 1 / the chance that a Class 7 origin respondent will end up in class 7.]

In my example, for Class 1 this is 80/20 divided by 30/120 = 16. Thus, the relative mobility prospects of Class 1 origin respondents are far superior to those of Class 7 respondents.

Individuals originating in Class 1 are 16 times more likely than individuals originating in Class 7 to reach a Class 1 destination rather than a Class 7 destination. If follows that individuals originating in Class 7 are 16 times less likely than individuals originating in Class 1 to reach a class 1 destination rather than class 7 destination.

Imagine instead that the odds ratio was 80/20 divided by 80/20 = 1. In this case, the relative mobility prospects of Class 1 and Class 7 respondents would be identical and on this measure we should have perfect equality of opportunity.

In practice, however the measurement of social mobility is more complex. Current studies of social mobility in the UK are usually conducted using the 7 Class NS SEC Scheme which would actually generate 441 potential odds ratios and render the overall measurement of social mobility trends very complex. [Thus for example one could calculate the Odds ratio for the relative chances that members of original classes 3 and 4 might reach destination classes 5 and 6 or that members of original classes 1 and 2 might reach destination classes 3 and4 and 439 similar possibilities!!]

The rates of upward and downward absolute social mobility depend upon the interaction of two factors

-

- If there is a change in the shape of the overall class structure involving the relative expansion of High Class employment and a relative decline of Lower Class employment one would expect the rate of upward absolute social mobility to increase.

- If the relative rate of upward social mobility increased , say due to educational reforms which improved the educational prospects of working class children, this would also generate increased upward absolute social mobility.

John Goldthorpe and his associates used this approach to the measurement of social Mobility in the so-called Oxford Social Mobility Study and recent trends in social mobility are analysed in detail in Social Mobility and Education in Britain[2019] by Erzsebet Bukodi and John H. Goldthorpe . I cannot summarise their detailed arguments here but in broad terms they draw the following main conclusions.

- Upward Absolute mobility did increase from the 1950s -1970s but this occurred almost entirely because of changes in the overall class structure which meant more high class employment became available. There was more room at the top.

- Changes in relative social mobility rates were very limited which meant that suggest that educational reforms between 1950s and the 1970s contributed little or nothing to increased upward absolute social mobility.

- Subsequently the growth of high class employment has slowed down which could be expected to result in reduced upward absolute social mobility or at least to a slower rate of increase.

- It is unlikely that the last 30 years of educational reform would serve to increase relative social mobility rates because middle class parents can adopt a range of strategies to try to ensure that their children continue to achieve higher grades than their working class peers. Click here for a podcast by Lee Eliot Major in which he explains why the UK education system fails to facilitate social mobility

These points are elucidated further in the following articles

Click here for John Goldthorpe on Education and Social Mobility and here and here for further information on Social Mobility and Education in Britain by E. Bukodi and J. Goldthorpe

It can also be noted that the children of the higher sections of the dominant economic class are especially likely to attend public schools and/or Oxbridge and other prestigious Russell universities and then to enter elite occupations in politics, law, industry and the military. Within this grouping have also developed kinship and friendship networks and shared social activities leading to intermarriage which contribute further to social cohesion and intergenerational stability. Wealthy parents also can use various methods to ensure that their children benefit more than poorer child from the operation of state education which increases the chances that state educated children of affluent parents can access elite occupation while educational success and entry to elite positions is far less likely for poorer children.

Click here for Guardian article on Social Mobility by Lee Eliot Majors and Stephen Machin. These authors have also written Social Mobility and Its Enemies [Pelican] in which they argue that for a variety of reasons recent educational policies have been relatively ineffective in promoting social mobility.

Click here for Guardian article on Social Mobility by Lee Eliot Majors and Stephen Machin. These authors have also written Social Mobility and Its Enemies [Pelican] in which they argue that for a variety of reasons recent educational policies have been relatively ineffective in promoting social mobility.

In The Class Ceiling it is argued that it is easier to secure progress to the higher levels of some professions if one possesses particular kinds of Elite cultural capital. Follow the links for further information, The Class Ceiling Slides Video

Education Data: Social Class, Ethnicity and Gender and Educational Achievement

- You may click here for recent data on relationships between social class, ethnicity , gender and educational achievement. In this document I am focusing upon relationships between social class and educational achievement.

- Data from annual Youth Cohort Studies indicated that GCSE pass rates were increasing for students in all social classes although social class differences in educational attainment remained considerable. Once the Youth Cohort Studies were discontinued social class differences in educational attainment came to be measured [albeit inadequately] in terms of the difference in the percentage pass rates of students eligible and ineligible for free school meals percentages and the GCSE attainment gap as between these groups has remained very considerable.

- The DfE has significantly modified its presentation of GCSE achievement data in the last 30 years but it is clear there has been a significant long term overall increase in the percentage of students achieving good GCSE results although there has sometimes been a slight decline in recent years as the Coalition Government attempted to address a perceived problem of grade inflation

- We should note also that progress is often assessed in terms of the attainments of the 70% or so of most successful 16 year olds but it is clear that much more needs to be done to help the 30% of relatively unsuccessful students. This should also lead us to question the use of comparable outcomes which ensures that around 30% or so of pupils will not gain 5 good GCSE passes. Surely there is a need for change here

- Click here for useful article on problems of examinations and assessment

- There are also significant differences in attainment at GCE Advanced Level as between students eligible and ineligible for free school meals [mainly because free school meals eligible students are less likely to enrol on GCE Advanced Level courses]. Consequently there are also significant differences in enrolment on Higher Education courses as between students eligible and ineligible for free school meals. Furthermore enrolment at "high status" universities is particularly low for free school meal eligible students and particularly higher for Private School pupils

Click here for further information on Private Schools

We may conclude that in recent years the educational attainments of free school meal eligible students have increased at GCSE and GCE Advanced Levels and that the rate of enrolment of free school meal eligible pupils on Higher Education courses has also increased but that the differences in educational attainment as between students eligible and ineligible for free school meals remain substantial at all levels of the education system.

To what extent are these trends in educational attainment explicable in terms of education policy changes in the last 30-40 years?

Sociologists have explained social class differences in educational achievement in terms of some combination of IQ theory [ which most sociologists criticise strongly] , theories which focus on material and cultural factors external to the schools themselves and internal organisational factors operative within the national education system and the schools themselves such as setting, streaming and mixed ability teaching. It is also argued that the existence of the Independent School sector makes some contribution to social class inequalities in educational achievement.

I have discussed the differing sociological approaches to the explanation of social class differences elsewhere on my site and students may click here and here and here for further details. However in summary the theories of Hyman, Sugarman, Douglas , Bernstein, Willis and Bourdieu suggest that in various ways working class subculture may help to explain the relative educational under-achievement of working class students.

However for a variety of reasons we should not automatically accept that working class students' relative educational underachievement can be explained by their cultural deprivation as suggested in the work of Hyman, Sugarman and Douglas. Bernstein always emphasised that his theories based on the differences between the working class restricted code and the middle class elaborated code meant only that there are social class differences in language codes not that working class language was culturally inferior. Also in various ways Willis and Bourdieu explained working class relative educational underachievement in terms of social class differences rather than working class cultural deprivation and it is clear also that working class educational underachievement can also be partly explained by various financial constraints and by factors internal to the schools involving processes of streaming, setting, labelling and self-fulfilling prophecy operative in the schools as in the work of Hargreaves, Keddie and Ball.. Working class parents and their children may hope for educational success but the children may fail to achieve it through no fault of their own.

There are disputes within Sociology as to the relative importance of cultural and material factors as determinants of educational attainment but there is nevertheless substantial agreement that the combined effects of these "external factors" are very significant. Thus for example in a 2007 study Robert Cassen and Geeta Kingdon argued that although schools do make a difference "while students' social and economic circumstances are the most important factors explaining their educational results about 14% of the incidence of low results is attributable to low school quality" and "disadvantaged kids are more likely to attend poorly performing and can miss out on best teaching due to the 5 A*-C target." [However this target has recently been replaced by the Progress 8 target]

Also Professor Stephen Ball in his study The Education Debate [3rd edition 2017] stated that there is good evidence that the variance in student attainment can be explained primarily by factors external to the schools and that although it is clearly important to investigate how changes in school organisation and teaching practices can improve the prospects of disadvantaged students it may be that "educational inequality might be better tackled not inside schools or families but by addressing poverty and inequalities in health housing and employment."

This view is reiterated in the recent study by Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin entitled Social Mobility and Its Enemies [2018]. Here the authors argue that while it is obviously true that all schools provide some education for all of their students and that some particularly effective schools compensate to a considerable extent for the adverse effects of some students' social background, "The truth is that schools can only do so much. They are governed by the 80/20 rule; on average 80% of the variation in children's school results is due to individual and family characteristics, while the remaining20% is due to what happens in school. Some schools are producing better results with very similar intakes of children. But the idea that teachers on their own can cancel out extreme inequalities outside the school is fanciful."

Also Professor Lee Elliot Major in his video lecture entitled Apocalypse or New Dawn: Social Mobility and Education post-Covid emphasises the relative importance of factors external to the schools as determinants of educational achievement. B. Bernstein had claimed in the 1970s that "Education cannot compensate for society" and these more recent studies confirm that there are limitations to what the schools themselves can achieve. However it must also be recognised that schools can have some impact on patterns of educational achievement

From the 1970s onwards proponents of school effectiveness research came to emphasis that there were significant differences in the examination results of schools with similar student intakes and this led to the development of research projects designed to uncover the specific factors promoting school effectiveness and to education policies designed to increase school diversity and parental choice as a means of increasing overall school effectiveness. [ In the second part of his recent lecture Professor Lee Eliot Major discusses some of the strategies which schools might use to reduce inequality of educational achievement ]

Thus successive governments argued that the development of the National Curriculum , the introduction of SATs at ages, 7, 11 and 14, OFSTED inspections and the publication of school league tables would enable parents to make a more informed choice among a wider variety of schools including at various times City Technology Colleges, Grant Maintained Schools, Specialised School, Faith schools , Academies , Free schools and University Technology Colleges as well as orthodox Local -Authority-Maintained Comprehensive Schools. Since the funding of all state schools was also to become much more dependent upon student numbers successive governments argued that this so-called quasi-marketisation of education would enable apparently effective, successful schools to expand at the expense of apparently ineffective schools [some of which would be forced to close] which was to drive up overall standards.

It was hoped also that socially and economically disadvantaged students who had for years been denied access to a good education would also benefit from this new approach to educational policy and they were to be helped further by compensatory education policies such as the Sure Start Programme and the Education Maintenance Allowance introduced by Labour Governments [1997-2010] and the Pupil Premium introduced by the Conservative- Liberal Democrat Coalition [2010-2015] .

More recently during her brief Premiership Theresa May expressed strong support for increasing the number of State Grammar Schools and also introduced plans to concentrate resources in geographical areas where social mobility is particularly low although it may be fair to say Theresa plans for education were marginalised by the loss of the overall Conservative Majority in the 2017 General Election by the need to focus upon Brexit negotiations which eventually led to Theresa May's resignation as PM. An initial critical assessment of the Opportunity areas programme is provided here

It is true that the educational attainments of free school meal eligible students have increased at GCSE and GCE Advanced Levels and that the rate of enrolment of free school meal eligible pupils on Higher Education courses has also increased but critics have argued that recent changes in education policy have done little if anything to narrow the gaps in educational attainment as between students eligible and students ineligible for free school meals.

Criticisms of Recent Education Policies

1.It is argued that quasi-marketisation has enabled more affluent parents to use their economic, social and cultural capital in various ways to secure entry for their children to the more effective state schools at the expense of disadvantaged children. These issues are discussed in some detail in the following two studies

In their study "Markets, Choice and Equity in Education " [1995] Ball, Bowe and Gerwirtz criticised Conservative education policies designed to provide parents with a wider choice of schools for their children because in their view middle class parents and their children would be especially likely to benefit from this choosing process because they possess the cultural and economic capital to choose more effectively. With regard to parental choice, Gerwirtz, Ball and Bowe distinguish between mainly middle class "privileged choosers" and mainly working class "semi-skilled and disconnected choosers" admitting however that these categories are , to some extent ideal types and that many parents may be difficult to classify exactly.

Privileged choosers are overwhelmingly middle class and are likely to opt either for private education or for the more successful state schools. To achieve this objective they may have purchased expensive houses in the catchment areas of effective state secondary schools; they may have chosen Middle Schools which are known to have especially good links with effective secondary schools ; they can afford to organise any necessary transport arrangements if the required schools are some distance away; they are both willing and able to take the time to assess information relating to examination results and related issues; they are comfortable in discussions with teachers and also ready to challenge them if they feel it to be necessary; they are familiar with sometimes complex application processes all of which puts them at an advantage in securing their children's entrance to the more effective schools.

By contrast "disconnected choosers" are primarily working class and are more likely to opt for their local neighbourhood school which consequently is likely to have a more working class intake. These parents certainly do show considerable interest in their children's education but their choice of secondary school is often not seen as especially important because "they typically see all schools as much the same". For this reason they are very likely to choose the secondary school in their own neighbourhood partly for reasons of convenience and partly because financial and time constraints inhibit their abilities to organise transport to more distant schools. They may also be influenced by friends, neighbours and relatives with similar views and their choice of school may to some extent reflect their sense of belonging to their own local, working class community. Thus the authors conclude that " choice is very directly and powerfully related to social class differences" and that " choice emerges as a major new factor in maintaining and indeed reinforcing social class differences and inequalities".

The ERA has also had important implications for the organisation of schools themselves as they must give more attention to marketing methods if they are to maintain student numbers and especially if they are to attract the middle class children who are most likely to boost league table performance. Individual schools may have some freedom of manoeuvre to decide upon their response to the implications of the ERA and if Governors, Head teachers and senior staff are very committed to the ideals of comprehensive education and do not face strong competition from rival schools the impact of the ERA may be limited . However this is unlikely and Ball et al suggest that the 1988 Education Reform Act has influenced school policy in several ways: it is more likely that resources may be diverted from actual teaching to improvements in the school buildings; new reception areas may be built; more professional prospectuses may be designed; open evenings are carefully choreographed; music and drama may be given a higher profile partly in and attempt to appeal to middle class parents.

Insofar as successful schools succeed in attracting increasing numbers of mainly middle class pupils via careful marketing of the good examination results the financial resources available to less successful schools in mainly working areas will decline leading to declining educational opportunities for the mainly working class pupils who still opt to attend these schools. The processes of increased parental choice under the terms of the Education Reform Act 1988 were therefore likely to result in increased inequality of educational opportunity.

In his 2003 study Class Strategies and the Education Market: The Middle Classes and Social Advantage Stephen Ball argues that upper and middle class children are likely to be more successful in education because upper and middle class parents can deploy economic capital, cultural capital and social capital to ensure that their children have educational advantages not available even to relatively affluent working class families and certainly not available to the poor.

Economic Capital

- Upper and middle class parents can afford to purchase relatively expensive houses in the catchment areas of successful state schools thus helping to ensure that their children will be able to attend such schools while working class children are more likely to attend less successful schools.

- If upper and middle class children are having educational difficulties their parents can afford to purchase additional relatively expensive private tuition for their children.

- If upper and middle class parents are dissatisfied with the quality of state education in their local area they can more easily arrange for transport to state schools located further afield, or they can relocate closer to more effective schools or they can opt to have their children educated privately. Private secondary education may be unaffordable for working class parents, costing as it may around £6000-£ 8000 per year even for non boarding pupils.

Cultural Capital

- Upper and middle class parents are often relatively well educated and will almost certainly be able to help their children with homework if this proves to be necessary.

- They are likely to have the confidence to believe that any educational difficulties experienced by their children can be resolved through discussion with teachers and are unlikely to assume that such difficulties are evidence of their children’s' limited academic abilities.

- They are more likely than working class parents to be able to interpret the fairly detailed statistics on school performance which are nowadays published and therefore better able to make an informed choice of schools for

- If popular schools are oversubscribed upper and middle class parents may be able to create favorable impressions which help to secure entry for their children to over- subscribed schools.

- They may socialise their children to present themselves sympathetically in the eyes of mainly middle class teachers.

- They may provide leisure activities for their children [such as Music, Drama and additional sporting activities] which enable the children to present themselves more effectively, for example in University interviews

Social Capital

- Upper and middle class parents may be in social contact with other upper and middle class parents who can help them to evaluate the relative effectiveness of different schools prior to school choice.

- They may know of particularly effective private tutors.

- They may be able to arrange particularly useful work experiences or contacts with personal friends who are university lectures which will enable their children to prepare far more effectively for university entrance.

Click here to access Parent Power: Sutton Trust Report 2018 by Rebecca Montacute and Carl Cullinane. In the introduction to the Report you will find a very good summary of the various factors which enable affluent, well educated parents to secure a range of educational advantages for their children much as was suggested in the above study by Professor Stephen Ball.

2.It is argued that that there is no conclusive evidence that Academies and Free Schools have increased the overall effectiveness of the education system or improved the relative educational opportunities of disadvantaged pupils; that the Coalition's inadequate funding of the Sure Start Scheme and the scrapping of the educational maintenance allowance were counterproductive and that the Pupil Premium , although well- intentioned, is insufficient to meet the real needs of disadvantaged pupils and may in any case have been used to offset the effect of spending reductions in other parts of the education system .

3 . Critics have also opposed the introduction of University tuition fees by the Labour Government and the subsequent significant increases the level of these fees by Coalition and Conservative Governments. It is true that despite these increased tuition fees Higher Education enrolment has increased among pupils eligible for free school meals but it may be argued that such enrolments would have increased much more rapidly if these fees had not been introduced and subsequently increased and these tuition fees are blamed for the significant reduction in enrolments of part-time students.

4. Despite the existence of various bursary schemes for less affluent studentsand various schemes whereby the state Private Schools were to share resources with the State Sector in various waysthe continued existence of private education [ and in particular the most prestigious "Public Schools" such as Eton and Harrow] is seen as providing unfair educational advantages for the children of parents who can afford to pay for it .Privately educated students are disproportionately likely to gain places at Oxford , Cambridge and the Russell Group Universities and subsequently more likely to find employment in high status, well paid occupations because of the higher status associated with degrees from these universities.

5. It is argued also that well privately educated persons are more likely to achieve occupational success than equally well educated state school persons because privately educated pupils are more likely to be able to afford to enroll of postgraduate degrees [Masters Doctoral programmes] and/or to take up unpaid internships and more likely to possess the kinds of cultural capital and social capital which appears to be necessary for career advancement in some professions. Click here and here for links to The Class Ceiling. Consequently for all of these reasons critics have argued that recent education policies have done little to increase equality of educational opportunity and that this helps to explain why relative rates of upward social mobility have changed little in recent years.

Click here for further information on recent English education policies

Click here and here and here and here and here for items on effectiveness of academies

Click here Guardian coverage of Free Schools

We may draw the following conclusions

Social class differences in educational attainment are determined mainly by factors external to the schools themselves which suggest that educational policies are likely to have a fairly limited effect on these differences.

Furthermore, in the era of austerity following the financial crash of 2008-9 it could be argued that reductions in government spending would serve to increase relative poverty and further inhibit the prospects for many working class pupils

Although it has been argued that the quasi- marketisation of state education could in principle improve average educational standards there are factors operative within the quasi-marketisation process which may well inhibit the progress of working class students.

The introduction of the Pupil Premium as a compensatory measure could be expected to provide some assistance to more disadvantaged students and important research has been done to increase the effectiveness of the scheme but it still seems entirely insufficient to offset the educational difficulties which disadvantaged students face

Meanwhile the continued existence of Private Education and the growth of Private Tuition offer preferential educational opportunities to those who can afford to pay for them. You may click here and here for additional information on the Private Independent Schools.

One of the most significant conclusions of social mobility studies is that rates of social mobility are lower in countries such as the USA and the UK which are relatively economically unequal and higher in the more economically equal societies such as the Scandinavian counties.

Finally upward social mobility for everybody id clearly impossible. In the era of COVID 19 it has become abundantly clear that we are dependent on our care workers, our shop workers and our drivers all of whom fulfill vital functions for which they are relatively poorly paid. People working in these occupations are not socially mobile but they certainly deserve a fair wage for what they do.