Gender and Educational Achievement: Part 3 of 5 : Part Three

Part Three: Explaining the relative improvement in female educational achievement since the late 1980s

Before attempting to analyse the reasons for gender differences in educational achievement I have included quite a lot of statistical information on the actual patterns of gender differences in educational achievement at GCSE, GCE Advanced Level and Degree Level. The main points in relation to students in England and Wales are as listed below and students might like to use some of the statistics to support these summary points . However they should be advised by their teachers as to how to summarise this data for examination purposes and should not spend too much time on the exact details shown in the subsequent charts and tables

- Even in the 1960s girls were outperforming boys in GCE Ordinary Level examinations although little attention was given to these overall statistics because boys were outperforming girls in the higher status subjects such as Mathematics and Science.

- Once the GCSE was introduced the gender gap in educational achievement began to increase as girls continued to outperformed boys in Languages and Humanities and reduced boys’ leads in Mathematics and Sciences. In terms of attainment of 5 or more GCSE A*-C grades in recent years 8-10 % more girls than boys have reached this standard.

- From 2016 onwards new criteria have been adopted to measure pupil achievement at GCSE level [EBacc, Attainment 8 and Progress 8.] Gender differences in attainment remain with these new measurement criteria.

- Girls outperform boys at GCSE level in every major ethnic group.

- For all pupils at GCSE level the attainment gap between pupils eligible for free school meals and all other pupils is greater than the attainment gap between boys and girls.

- However, this total figure arises because of the large FSM/Other attainment gaps among British and White pupils which make up a large proportion of the total. In several ethnic minority groups, the gender gap is greater than the FSM/Other Gap.

- There are some significant gender differences in subject choice at GCSE level, but these occur mainly in minority subjects

- less notice that the number of girls taking Advanced Level subjects is greater than the number of boys so that despite boys' higher percentages of top grade passes the gender difference in the number of top grade passes is small.

- The gender differences in subject choice are greater at Advanced Level than at GCSE Level.

- Gender differences in GCE Advanced Level pass rates are smaller than at GCSE

- It has been claimed that girls’ grades improve relative to boys’ grades when coursework accounts for a greater proportion of the overall assessment and vice versa

- There are significant gender differences in choice of vocational courses

- More females than males enrol on undergraduate courses.

- Once again there are significant gender differences in subject choice with important implications for future gender differences in employment.

- Females are now more likely than males to gain First Class and Upper Second Class first degrees

- Gender and Recent GCSE Results 2016-2023

In 2015 new measures of pupil achievement at GCSE Level were introduced and pupil achievement is now assessed in terms of the percentages of pupils entering the English Baccalaureate, the percentages of pupils achieving grades 5 or above in English and Mathematics GCSEs, the average Attainment 8 score of all pupils and the Average EBacc score per pupil. Also a Progress 8 measure is used to assess the relative performances of schools as a whole.. [Click here BBC item on technicalities of Attainment 8 and progress 8 and here for a very technical article

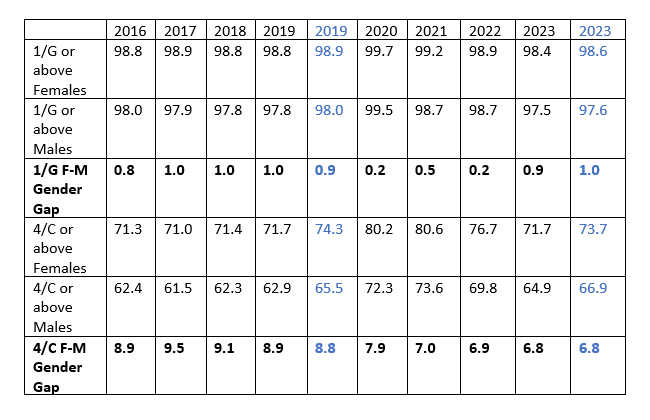

Percentages of Male and Female Student Entries and GCSE Examination Grades Cumulative Percentages UK 2016-2023.

In the following table Black data refer to All UK students and the blue data refer to English Students aged 16

Females outperformed Males at GCSE Level throughout 2016- 2021. Once examinations were cancelled in 2019 the gender gap as measured by percentages of males and females attaining grades 4/C or above fell but as measured by percentages of males and females gaining 7/A or above the gender gap increased. When examinations returned in 2022 the gender gaps at grades4/C and above and 7/A and above both narrowed.

However data on Free school meal eligibility indicate that many girls still underachieve at school and it is vital that we do not neglect the importance of the continuing relative under-achievement of many working class girls and especially of many girls eligible for free school meals [FSM] You may click here for Professor Gillian Reynolds article [2018 ].For a recent BBC Series Love and Drugs on the Streets Girls Sleeping Rough - Click here to see that poverty may impact adversely of female educational achievement.

Click here for Gender Differences in Achievement at Key Stage 4 2018/19- 2022/23 which illustrate the gender differences as measured by the several criteria listed above.

Data on Gender, Free School Meal Eligibility 2018/19- 2022/23

For many years the main measure of attainment at GCSE level was the percentage of pupils achieving 5 or more GCSE passes at grades A*-c including English and Mathematics , In summary between 2008/9 and 2014/15 on this criterion the gender gap varied between 7.3% and 10.1% and the FSM gap varied from 26.3 % and 27.8% It is very important to note however that as a result of methodological changes introduced in 2013-2014 results in 2013/14 and 2014/15 are not comparable to earlier results.

Currently data are published on a range of criteria and the sizes of the gender gap and FSM gap vary depending upon the criteria chosen as is indicated via the following links.

Click here for gender and attainment 2018/19- 2022/23

Click here for FSM eligibility and attainment 2018/19- 2022/2023

In the following tables I have extracted data on the percentages of pupils achieving GCSE grades 4 or above in English and Mathematics and leave students to extract the data on percentages of pupils achieving the English Baccalaureate [grades 4 or above in English and maths, A*-C in unreformed subjects.]

Percentages of pupils achieving GCSE grades 4 or above in English and Mathematics 2018/19- 2021/22

| 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2923/24 | |

| Girls | 68.4 | 75.0 | 75.4 | 71.5 | 67.4 | |

| Boys | 61.0 | 67.6 | 69.2 | 66.2 | 62.4 | |

| Gender Gap | ||||||

| FSM all other | 68.4 | 75.4 | 77.1 | 74.5 | 71.3 | |

| FSM eligible | 41.4 | 49.2 | 50.9 | 47.0 | 42.7 | |

| FSM eligibility gap |

Activity1. Using information in the above table on Gender, Free School Meal Eligibility and Educational Attainment answer the following questions.

Activity 2. Percentages of pupils achieving the English Baccalaureate [grades 4 or above in English and maths, A*-C in unreformed subjects.] 2018/19- 2022/23

Use the following links to see the data to complete the above table. Click here for gender and attainment 2018/19- 2022/23 Click here for FSM eligibility 2018/19- 2022/2023. Comment on the Gender and FSM gaps using this criterion. Compare the Gender and FSM Gaps in the two tables. Which factor seems to be the more significant influence on educational achievement: Gender or Free School Meal Eligibility? Which factor seems to be the more significant influence on educational achievement: gender or social class? However, it is important to consider interrelationships between gender, free school meal eligibility and ethnicity. It can then be shown that the overall size of the free school meal eligibility/FSM all other students gap is heavily influenced by the size of the gap among white British students who are a large majority of the total student cohort. For some ethnic groups the FSM eligibility gap is much smaller than it is for White British students. - |

Gender, Ethnicity and Free School Meal Eligibility at GCSE Level

You may Click here for 2021/22 data on Ethnicity, Free School Meal Eligibility and Achievement at Key Stage 4 .and you may also click here for 2021/22 data on Ethnicity, Gender and Achievement at Key Stage 4

You may Click here for 2022/23 data on Ethnicity, Free School Meal Eligibility and Achievement at Key Stage 4 .and you may also click here for 2022/23 data on Ethnicity, Gender and Achievement at Key Stage 4. . [ These attainment data for 2022/23 are in general slightly lower than in 2021/22 although the patterns of attainment are very similar and I shall update the 2021/22 data very soon.]

Ethnicity, Gender, Free School Meal Eligibility and Attainment 8 Score of all pupils by ethnicity. England

Average Attainment 8 score 2021/22 England

| Boys | Girls | FSM Eligible | All Other Pupils | ||

| Total | 46.3 | 51.4 | 36.9 | 51.9 | |

| Asian Total | 52.2 | 57.2 | 46.6 | 56.8 | |

| Any other Asian Background | 54.3 | 60.0 | 47.9 | 59.2 | |

| Bangladeshi | 52.2 | 56.6 | 49.4 | 56.7 | |

| Indian | 59.1 | 63.6 | 50.5 | 62.4 | |

| Pakistani | 46.4 | 51.9 | 43.8 | 50.9 | |

| Black Total | 44.9 | 52.4 | 43.7 | 51.0 | |

| Any other Black Background | 42.7 | 51.4 | 42.5 | 49.1 | |

| Black African | 47.3 | 54.5 | 46.3 | 53.0 | |

| Caribbean | 37.9 | 45.6 | 36.5 | 44.7 | |

| Chinese Total | 63.5 | 68.9 | 58.4 | 66.8 | |

| Mixed Total | 46.8 | 52.1 | 38.9 | 53.5 | |

| Any other Mixed Background | 48.6 | 53.9 | 41.0 | 54.7 | |

| White and Asian | 52.3 | 57.5 | 41.4 | 58.2 | |

| White and Black African | 46.2 | 51.8 | 41.4 | 54.2 | |

| White and Black Caribbean | 39.0 | 45.1 | 34.6 | 46.6 | |

| Any Other Ethnic Group | 46.8 | 52.9 | 43.6 | 52.8 | |

| Unclassified | 40.5 | 45.1 | 37.1 | 44.3 | |

| White Total | 45.5 | 50.3 | 33.5 | 51.1 | |

| Any Other White Background | 48.4 | 53.2 | 41.4 | 52.4 | |

| Gypsy Roma | 18.3 | 23.6 | 17.9 | 24.4 | |

| Traveller of Irish Heritage | 24.3 | 33.2 | 22.7 | 37.0 | |

| White British | 45.3 | 50.2 | 33.2 | 51.1 | |

| White Irish | 51.8 | 57.8 | 37.4 | 58.3 | |

You may use the above table to answer the following questions.

- For all pupils what is the percentage gap in attainment between pupils eligible and ineligible for free school meals?

- In which broad ethic category is the gap in attainment between pupils eligible and ineligible for free school meals greatest?

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Chinese pupils.

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Indian pupils.

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Bangladeshi pupils

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Pakistani pupils.

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Black African pupils.

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Back Caribbean pupils.

- Comment of the free school meals attainment gap for White and White British pupils.

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Gypsy Roma pupils.

- Comment on the free school meals attainment gap for Irish Traveller pupils.

Ethnicity, Gender, and Free School Meal Eligibility

- You will also find that females outperform males in every ethnic category.

- The overall attainment gap between pupils eligible and ineligible for free school meals is greater than the overall attainment gap between female and male pupils in every ethnic group.

- Notice that the FSM eligibility gap s particularly high for White and White British pupils

Further information on Gender, Ethnicity sand free school meal eligibility may be found here

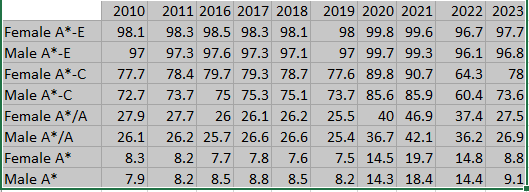

Gender and Overall GCE Advanced Level Subject Entries and Pass Grades 2010-23

You May also Click Here to Download an Excel Chart of this Data for 2022

You May also Click Here to Download an Excel Chart of this Data for 2023

There are always considerable controversies around the publication of A level statistics. For example, when in recent years [[2016-2019] Male students have achieved a higher proportion of A* Grades than Female students it has been suggested that this could be explained partly by the fact that Males were likely to outperform Females in a relatively small number of subjects [e.g. Mathematics] where examination entries and proportions of A/A* grades awarded were particularly high and that females nevertheless continue to out -perform males in many individual subjects.] Click here for an item on A Levels from the BBC's More or Less

It is also pointed out that total female A Level entries are far greater than total male A level entries so that even where a larger percentage of male than female subject entries are awarded A* grades the number of male and female A*grade awards is very similar. Click here for an article from The Conversation

Recent data indicate that in GCE Advanced Level Examinations males’ results did improve relative to females’ results once coursework was excluded from assessments. Male A* rates were consistently higher than female A* rates 2016-2019 but in terms of A* /A grades the gender gap fluctuated. However, it should be noted that the relative changes in males’ and females’ results following the ending of coursework were small as is indicated in the above table.

In the years of CAGS [2020 and 2021] females outperformed males at A* and A*/A grades, but the female lead declined once examinations were reintroduced in 2022. You may click here for more detailed information on GCE Advanced Level Results 2019-2022

There are also important gender differences in subject entry at GCE Advanced Level and you can find updated information on Gender and Subject entry here.

- Further and Higher Education

The following data illustrate that until 1991 Males were more likely than females to embark on undergraduate courses but this gradually changed in the course of the 1990s and the reverse is now the case. More recent data are provided after this earlier table

Table : Students in further and higher education: by type of course and sex1970/71 2008/9 [United Kingdom: Thousands]

| MALES | FEMALES | |||||||||

| 1970/71 | 1980/81 | 1990/91 | 2006/07 | 2008/09 | 1970/71 | 1980/81 | 1990/91 | 2006/07 | 2008/09 | |

| Further Education | ||||||||||

| Full-time | 116 | 164 | 219 | 515 | 95 | 196 | 261 | 531 | ||

| Part-time | 891 | 697 | 768 | 1,027 | 630 | 624 | 986 | 1,567 | ||

| All further education | 1,007 | 851 | 986 | 1,542 | 725 | 820 | 1,247 | 2,098 | ||

| Higher Education | ||||||||||

| Undergraduate | ||||||||||

| Full-time | 241 | 277 | 345 | 563 | 593 | 173 | 196 | 319 | 706 | 735 |

| Part-time | 127 | 176 | 148 | 267 | 262 | 19 | 71 | 106 | 451 | 424 |

| Postgraduate | ||||||||||

| Full-time | 33 | 41 | 50 | 120 | 137 | 10 | 21 | 34 | 124 | 132 |

| Part-time | 15 | 32 | 46 | 143 | 114 | 3 | 13 | 33 | 181 | 160 |

| All higher education | 416 | 526 | 588 | 1,094 | 1106 | 205 | 301 | 491 | 1,463 | 1451 |

[Home and overseas students attending further education or higher education institutions. See Appendix Part3 Stages of Education.2. Figures for 2006/07 include a small number of higher education students for whom details are not available by level. Source:: Department for Children , Schools and Families, Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills, Welsh Assembly Government, Scottish Government, Northern Ireland Department for Employment and Learning.] [From Social Trends 2009 and 2011: Crown Copyright]

More Recent Data on Higher Education

Click here for DfE publication: Widening participation in higher education 2021

Click here for HE Student Enrolments and Personal Characteristics 2016/17 - 2020/21. Females continue to be more likely than males to enrol for Higher Education Courses. Some students self- identify as "Other" rather than male or female

Click here for HE Enrolments by Subject Area and Sex. The gender differences in subject choice which occur at Advanced Level continue in Higher Education.

Gender Differences in Degree Results 2011/12- 2020/21 . Click here and scroll down to figure 16 for latest data]

In 2013/14 females were very slightly less likely than males to be awarded First Class degrees but significantly more likely than males to be awarded Upper Second Class degrees. However, since 2016/17 females have been more likely than males to gain both First Class and Upper Second Class degrees the reverse was the case.

| 1st Class % | 2:1% | 2.2% | 3rd/Pass % | |

| Males 2017/18 | 27 | 46 | 21 | 5 |

| Females 2017/18 | 28 | 50 | 18 | 4 |

| Other 2017/18 | 33 | 48 | 15 | 4 |

| Males 2018/19 | 27 | 46 | 21 | 5 |

| Females 2018/19 | 29 | 50 | 18 | 4 |

| Other 2018/19 | 33 | 45 | 19 | 3 |

| Males 2019/20 | 34 | 46 | 21 | 5 |

| Females 2019/20 | 36 | 48 | 14 | 3 |

| Other 2019/20 | 41 | 40 | 17 | 3 |

| Males 2020/21 | 35 | 46 | 16 | 3 |

| Females 2020/21 | 37 | 46 | 13 | 3 |

| Other 2020/21 | 45 | 43 | 9 | 3 |

| Males 2021/22 | 31 | 46 | 19 | 5 |

| Females 2021/22 | 33 | 47 | 16 | 5 |

| Other 2021/22 | 38 | 44 | 15 | 3 |

Useful Links

Click here for a report from HEP1 on the underachievement of young men in higher education and here for Guardian coverage of this report May 2016

Click here for Mind the Gap: Gender Differences in Higher Education [Rachel Hewitt; 2020]

Click here for Equality of access and outcomes in higher education in England [House of Commons Library Briefing Paper June 2021]

Click here for a link to the relevant research

- The relative improvement in female educational achievement since the late 1980s : Explanations

Girls have traditionally outperformed boys especially in English, Foreign Languages and Humanities subjects and relative female examination results have increased in these subjects since the late 1980s while female examination pass rates in Science subjects and Mathematics have also improved significantly. It is important to note that, prior to the introduction of the National Curriculum in 1988 , Sciences were optional subjects at 16+ level and especially Physics and Chemistry were studied disproportionately by boys and Biology disproportionately by girls. Since the Sciences are now compulsory subjects under the terms of the National Curriculum , they are studied equally by boys and girls, and girls have caught up and in some years overtaken boys in Science examinations and narrowed the gap in GCSE Maths and this combined with their traditionally higher examination pass rates in English, Foreign Languages and Humanities subjects explains why they are now significantly more likely to out perform boys at GCSE Level. {Boys and girls are about equally likely to study "Sciences" at GCSE Level and although boys have traditionally been more likely than girls to study Single Science examinations by 2017 girls were slightly more likely than boys to study GCSE Biology and Chemistry while boys remained slightly more likely than girls to study GCSE Physics.]

In outlining some of the explanations for relative female educational improvement since the 1980s we may distinguish between biologically based explanations and sociologically based explanations.

- Biologically Based Arguments

- Whereas in the past there were attempts to explain the relative educational under-achievement of girls in biological terms, there are attempts nowadays to explain the improved achievements of girls in biological terms. Thus it is suggested that because girls mature physically earlier than boys, they also mature intellectually earlier than boys. Consequently:

- by the ages of say 13-14, girls are on average more sensible;

- they have greater powers of concentration;

- they can organise coursework tasks more efficiently.

- It has been suggested also that even young female infants can be shown to have superior language skills relative to young male infants and that these differences in language capabilities may well be innate.

- However sociologists argue that even if these biological factors provide part of the explanation for gender differences in educational achievement, they cannot provide the entire explanation because:

-

- girls educational performance depends upon factors other than their physical maturity;

- if girls do , on average, have superior linguistic skills , this may be explained at least partly by the fact that females are more likely to have been socialised by their mothers and/or first school teachers to see reading as a "feminine activity". Meanwhile it could be suggested that many traditionally minded fathers may allegedly wish to socialise their sons to play football and undertake other stereotypically masculine leisure pursuits rather than to indulge in the detailed study of English Literature which is seen as a stereotypically feminine activity;

- many boys [especially upper and middle class boys] are more sensible, have greater powers of concentration, can organise coursework more sensibly and achieve better examination passes than many girls [ and especially working class girls] all of which suggests that gender differences in examination success do not derive solely from gender differences in physical maturity.

- Sociologically Based Explanations

Sociologists have argued that gender differences in educational achievement can be explained by a wide range of social factors. They also often distinguish between factors which are External and Internal to the organisation of the education system while recognising that in some cases these external and internal factors may be interconnected in various ways

External Factors

- In the first half of the 20th Century many women left employment following marriage and took on the roles of full-time housewives and mothers and, in so doing provided very significant role models for their own daughters who were consequently likely to see their futures also as full time housewives and mothers rather than in terms of gaining a better education and pursuing rewarding employment opportunities which at this time were in any case rarely available to women.

- However the second half of the 20th Century saw significant changes in the occupational structure occurring as a result of the growth of industries based upon light assembly work, the Welfare State and the financial and commercial sectors of the economy which created more employment opportunities for women, mainly in light assembly work, retailing and secretarial work but also to some extent in some professional occupations such as teaching , nursing and social work and to a lesser extent in finance and in law..

- Many married couples recognised quickly that they could improve their family living standards very significantly if married women returned to work even while their children were still young .

- The increased availability of labour saving goods combined with some increased willingness of some husbands to help with housework and childcare and the increased opportunities for adult social interaction at work all made returning to employment an attractive option for many married women. Consequently these working mothers were now providing much different role models for their daughters to follow.

- The number of lone parent families has increased and since many lone parents combine caring for children with paid employment this may encourage daughters to focus more on their education as a means of improving their future employment prospects. Also , very unfortunately, some lone parents may for a variety of reasons be unable to find paid employment which could well lead to financial hardship. Their daughters may come to realise that personal relationships may sometimes be precarious and that a good education followed by secure employment may help them to a better life.

- Parents have increasingly recognised that a wider variety of employment opportunities are becoming available and have become more likely to encourage their daughters to think in terms of securing the good educational necessary to access such careers. Girls and boys in all social classes express more interest in Further and Higher Education although it may be that this is less the case in some sections of the working class and unfortunately even when working class parents wish to support their children's educational progress they may [ in Bourdieu's terminology] lack the economic, social and cultural capital necessary to provide truly effective support.

- Perhaps the best known study which emphasised the importance of gender socialisation as an influence on educational achievement was Sue Sharpe's "Just Like a Girl[1976]. Sue Sharpe concluded on the basis of a study of mainly working class girls in London in the early 1970s that their main concerns were "love, marriage, children, jobs and careers more or less in that order." Clearly, if these girls saw careers as a relatively insignificant priority , they would have been unlikely to attach much importance to the gaining of educational qualifications.. [However when she repeated the research in the 1990s, she found that careers ranked much more highly in the order of girls' priorities which could have been a factor contributing to their increasing education achievement] Nevertheless Click here for Professor Gillian Richards' more recent article on the lives of working class girls in which she argues that for a variety of reasons the career aspirations of some working class girls may remain limited . NEW link added April 2018

- Sociologists had often noted that a large proportion of infant and primary school teachers were women and that this may have reinforced the traditional view that women were especially suited for childcare rather than "real work" since this early years teaching was perceived as simply an extension of the mothering role. However by the 1980s it began to be argued that because young children were being taught to read mainly by women [their mothers and/or female teachers], this strengthened the children's' perception that reading was mainly a female rather than a male activity which is now believed to help to explain the relatively rapid linguistic development of girls. Click here for recent research on gender, teacher expectations and pupils' self-images [Partly external reference to parents combined with a partly internal reference to teachers

| Activity

1.In the first half of the 20th Century many married women were full-time housewives. How may this fact have affected female attitudes to education? 2 What factors encouraged an increasing proportion of married women to remain in employment after marriage in the second half of the 20th Century?. 3 How may the increased employment of married women have affected their daughters' attitudes to education? 4.Why might reading be perceived by some children as a female rather than a male activity? Is this more likely to be the case among working class children than among middle and upper class children? |

9. Feminist political activity had helped to persuade governments to introduce the Equal Pay act of 1970 and the Sex discrimination Act of 1975 which outlawed both the payment of unequal wages to males and females for equal work and various forms of discrimination in the workplace and in the education system. These Acts have been insufficient to remove all gender discrimination but they have contributed to a climate in which female employment opportunities could improve. which increased female career aspirations while schools themselves developed specific Equal Opportunities provisions designed to remove discrimination on the basis of disability, ethnicity, gender and sexuality..[Partly external reference to the labour market and partly internal reference to schools]

10. Female employment opportunities increased further from the 1970s onwards as a result of the growth of the Service Sector of the economy which resulted in the growth of employment opportunities considered suitable for women. Much of the new service sector employment involved relatively low pay but some new well paid professional jobs were created and their increased availability may have provided a stimulus for more female students to prioritise education.

11.By the 1980s Feminist ideas became increasingly influential both in the wider society and within the education system [Partly external and partly internal] Even if few teenage girls in the 1980s would have actively described themselves as feminists, it is likely that they were influenced increasingly by feminist ideas. particularly those of the liberal feminist variety, which seemed to confirm many of their own experiences of life. For example

(A) These girls may have seen that their mothers had been denied good employment opportunities partly because of their limited education;

(B) They saw that their full-time employed mothers were still forced to shoulder a disproportionate share of housework and childcare responsibilities and that they themselves were often forced to help around the house more than their brothers;

(C) They saw that actual marital relationships were not heavily based upon romantic love;

(D) That the housewife-mother role might offer only limited personal fulfillment;

(E) They saw that marriages were increasingly likely to end in divorce which meant that divorced women might be forced to support themselves and their children financially in later life and that better educational qualifications would enable them to do so.

Feminists argued that women were entitled to equal rights in education, in the family and in employment and as a result more female students came to think that if they were likely to spend more time in paid employment, they might prefer an interesting, well paid career as an alternative to marriage, or to pursue a career and marry a little later or that they might wish to return to their career after marriage or that a career would provide them with financial security if their marriage should increase in divorce which was statistically increasingly likely. Sue Sharpe’s repetition in 1994] of her 1970s research showed that in the 1990s, female school students were now attaching much more significance to their careers and as a result giving increasing priority to their education.

| Activity

1. How may female attitudes to education have been affected by the implementation of the Equal Pay Act and the Sex Discrimination Act? 2. How might female attitudes to education have been affected by the growth of the Service Sector of the economy? 3. Find out about the differences between liberal, radical and Marxist feminism. How do attitudes to education differ among these different types of feminists? The answers to this question would require another document and you should discuss it with your teachers. 4. How might female attitudes to education have been affected by their increased recognition of the possible instability of married life?

|

Internal Factors

Feminists of the 1960s to the 1980s had undertaken several detailed studies [such as those mentioned in the previous section of this document] which had pointed to the educational disadvantages suffered by female students and as a result education policies were gradually adopted which could be expected to improve female educational prospects at least too some extent.

- Teacher Training courses and school inspections have given increasing attention to gender equality issues and gender biases textbooks and other resources may have gradually improved although even in 2018 concerns have recently been expressed that some gender biases continue to exist.

- Careers Education advisers have increasingly emphasised that a wider variety of careers are becoming available to women and this may have encouraged more girls to prioritise their education.

- The National Curriculum made Sciences compulsory for all at GCSE level which increased the proportion of females taking these subjects.

- The initiatives of organisations such as GIST [Girls into Science and Technology] and WISE [Women into Science and Engineering] may have helped to make the sciences more attractive to females although the effectiveness of these initiatives should not be overstated. In the GIST programme[1979-1983] researchers worked in 10 co-educational comprehensive schools to try to raise teacher awareness of equal opportunities issues and to encourage more girls to opt for Sciences at GCE and CSE levels. The final report concluded that the initiative had improved girls' attitudes to Science and Technology only slightly ; that girls' enrolments in GCE and CSE Science increased only slightly; and that the teachers , although sympathetic to the programme said that they had not modified their teaching practices substantially as a result. However the GIST initiative could be regarded as an early pilot programme which has encouraged many subsequent equal opportunities initiatives. The WISE programme was set up as a national initiative by the Equal Opportunities Commission and the Engineering Council and was designed to raise awareness of the need for more female scientists and technologists and to emphasise the attractiveness for girls, young women and older women seeking to retrain of careers in Science and Technology.

- WISE is still in operation and its website indicates that the employment of women in STEM occupations is gradually increasing but that further improvement is necessary.

- The introduction of the GCSE resulted also in the introduction of course work as a means of assessment alongside examinations and a coursework element was soon introduced also into Advanced Level courses.

- Some explained the relatively rapid improvement in girls' educational achievements once the GCSE had been introduced mainly in terms of girls' allegedly superior organisational skills which enabled them to complete the newly introduced coursework tasks more effectively. However, it can also be argued, for example, that coursework assignments test especially depth of understanding as well as organisational skills. It soon came to be argued assessment by coursework was unreliable because students might receive assistance in its completion and consequently course was gradually phased out in most GCSE and Advanced Level subjects.

- The extent to which females have been advantaged by the increased use of coursework as a scheme of assessment is uncertain. Francis and Skelton [2005] quote evidence to the effect that even in the era of GCE ordinary level examinations, females were likely to outperform males and that their results began to improve before coursework was introduced.

- However a detailed recent research paper from Ofqual concludes that ”Male students perform better than female students in wholly examined GCSE specifications and also in GCSE specifications where there is a greater level of control in the coursework. Female students tend to have better outcomes than males where internally set, internally marked coursework is included.” Also in a Guardian article from 2018 Jon Andrews [who is deputy head of research at the Education Policy Institute] comments in relation to the 2018 GCSE results that “The move away from coursework is thought to benefit boys in particular”. Nevertheless, despite the discontinuation of coursework the GCSE gender gap, although slightly reduced, remained substantial and it seems clear that girls' relative educational improvement must be explained by a wide ranging combination of factors operative inside and outside of the schools rather than solely by changes to the system of assessment.

- Also as schools were assessed and located in published league tables on the basis of school examination performance it made no sense for them to neglect the factors restricting girls' educational performance [although some have argued that the "excessive attention" given to the difficulties of girls results in a neglect of the difficulties of boys.

- It could be that in the era of quasi -marketisation of education high performing schools might be especially keen to recruit girls' whose higher attainments at GCSE level would help to sustain these school' high league table positions. However gender differences in attainment at Advanced Level are far less clear cut and subject to competing interpretations. For example in 2017 a larger percentage of male entrants than female entrants gained A* grades but since the entry rate of females was higher more females than males gained A* grades at Advanced Level.

- As it has increasingly been recognised that girls are likely to out -perform boys at GCSE level it may well be that girls have been more likely to be positively labelled than boys leading to the relative improvement of girls' educational performance. However it has also been suggested, for example by Louise Archer , that it even by 2005 it was still middle class white boys who were most likely to be perceived by teachers as 2Ideal pupils.2 This is an issue that you might like to discuss further with your teachers.

| Activity

8. How may recent educational changes have encouraged female educational aspirations? |

The combined effects of the above factors mean that nowadays many more women are in paid employment in general and that a growing minority of well educated women are employed in a widening range of interesting well paid careers. These successful women must surely provide positive role models for girls whose interest in education has in any case increased and as their rate of progress increases successful girls may experience positive labelling from teachers which will enhance their prospects still further.

Issues for Further Study

Discuss these interconnections with your teachers. |

Boys, Girls and Achievement :Addressing the Classroom Issues : Becky Francis[2000]

[See also Reassessing Gender and Achievement: Questioning contemporary key debates: Becky Francis and Christine Skelton 2005 for more information on all aspects of the relationships between Gender and Educational Achievement]

The findings of Becky Francis in this study encapsulate many of the above points . She argue that in so far as girls are improving more rapidly than boys , this is to be explained primarily in terms of the processes affecting the social construction of femininity and masculinity. In relation to the social construction of femininity, she argues that many girls of middle school and secondary school age aim to construct feminine identities which emphasise the importance of maturity and a relatively quiet and orderly approach to school life. Girls certainly do take considerable interest in their appearance and may choose to rebel quietly by talking at the back of the class or feigning lack of interest but , according to Becky Francis, not in a way which will detract from their school studies. Their femininity is constructed in such a way that if they choose to behave sensibly and work hard this, if anything, adds to their femininity.

No evidence is found to the effect that girls nowadays worry that evidence of intelligence and hard work may render them unattractive to boys and attitudes within female friendship groups are likely to strengthen rather than undermine girls' commitment to their school work. although ,admittedly , however, girls do not wish to be perceived as "nerds", interested in school work and nothing else. Increasingly also by comparison , say with the girls interviewed by Sue Sharpe in the first edition of "Just Like a Girl" teenage girls nowadays have gradually come to prioritise the importance of gaining good academic qualifications as a means of improving their own career prospects rather than assuming that their future employment is likely to be of secondary importance by comparison with their likely future roles as housewives and mothers.

Thus the girls in Becky Francis sample express interest in a relatively wide variety of careers; are relatively unlikely to favour stereotypical female careers such as nurse, clerical worker or air hostess ; are quite likely to express interest in careers usually associated with men and very likely to express interest in careers for which further education, higher education and a degree will be necessary. However broadly traditional patterns of career choice do remain in that the girls are more likely to choose careers associated with the Humanities or the caring professions than with Science, Mathematics or Engineering. Also very importantly the girls believe strongly that they are likely to face gender discrimination in employment and Becky Francis sees this as a major reason why girls are increasingly keen to work hard to achieve good educational qualifications.

This is clearly a very useful study which rightly focuses heavily on the social constructions of masculinity and femininity as key influences on male and female educational achievement. Becky Francis presents a very positive description of secondary school girls' femininity which helps them in several ways to make educational progress. However I am sure that she would recognise that not all female students approach school in such a positive way and that many female students [mainly working class female students] adopt their own forms of anti-school pupil which undermine their educational prospects in much the same way as "laddish" behaviour undermines the educational prospects of many mainly working class male students.

Very importantly in some of her subsequent Professor Francis has given considerable attention to the gender identities of high achieving pupils and noted that in some cases it might prove difficult for high achieving pupils to attain social acceptability among their fellow students.

Click here for a brief analysis of the Gender Identities of High Achieving Pupils by Professor Becky Francis. This is a very interesting item which might provoke considerable class discussion.

Becky Francis’ study [2000] was based upon an investigation of mainly working class pupils in three London secondary schools. She noted that in general the girls had more ambitious career aspirations than the boys with more girls than boys intending to apply for HE courses. However, she does also note that there were also some girls [although fewer than in the case of boys] who were not taking their academic studies seriously.

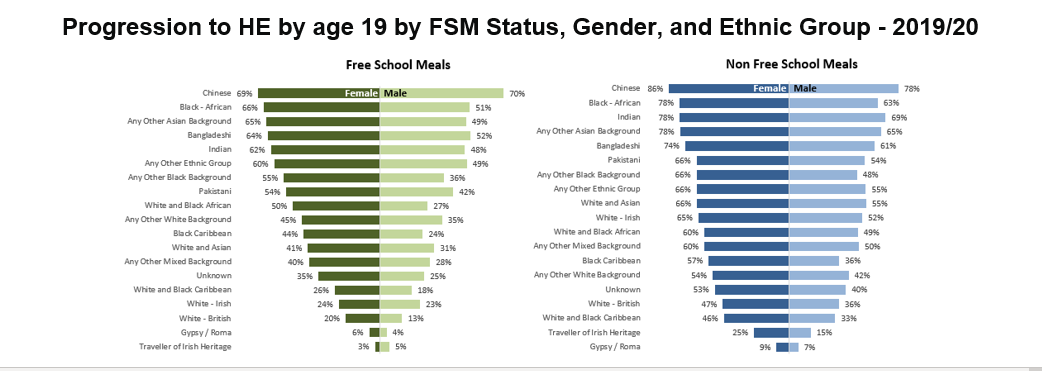

Most recent data indicate that on a national level females in all major ethnic groups have been more likely than males to enrol on HE courses although there are also very significant differences in enrolments as between females and males eligible and ineligible for free school meals. [Click here for DfE publication: Widening participation in higher education 2021.]

Progression to HE by age 19 by FSM Status, Gender, and Ethnic Group - 2019/20

- Note that progression rates can be volatile over time due to the very small number of pupils in some categories. This is particularly the case for Gypsy/Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage pupils

Source: Matched data from the DfE National Pupil Database, HESA Student Record and ESFA ILR

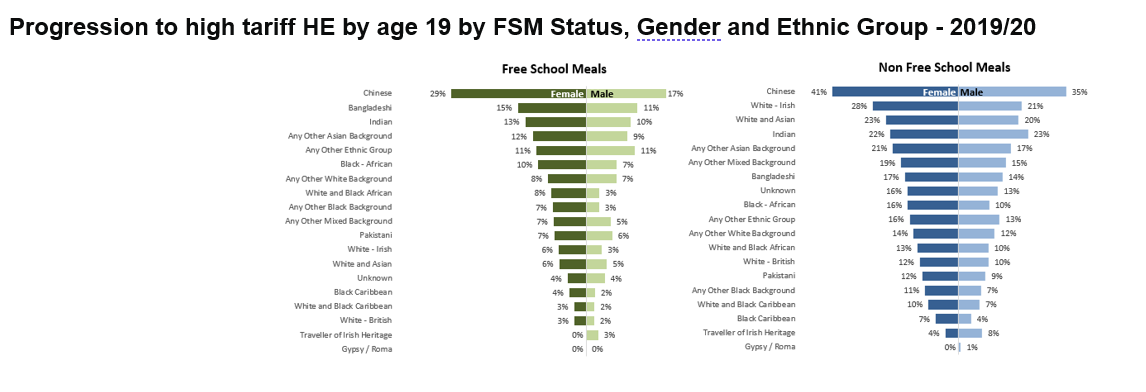

Progression to high tariff HE by age 19 by FSM Status, Gender and Ethnic Group - 2019/20

- Note that progression rates can be volatile over time due to the very small number of pupils in some categories. This is particularly the case for Gypsy/Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage pupils

Source: Matched data from the DfE National Pupil Database, HESA Student Record and ESFA ILR

Also, in a recent study Professor Gillian Reynolds has shown that the career aspirations of some working class girls in areas which have recently experienced high levels of deindustrialisation are shown to be limited. [ You may click here for Professor Gillian Reynolds article working class girls.] These two sources show that many working class girls’ aspirations may be limited by their social circumstances and that even when they are ambitious, these ambitions may be thwarted through no fault of their own.

Although females are in general more likely than males to enrol on HE courses, they remain less likely than males to apply on several STEM courses which show that for a variety of reasons, many ambitious females’ career aspirations do not lie in that direction. Since fewer women are enrolling on STEM courses, STEM occupations continue to be dominated by men especially at the highest levels and this is likely to continue to dissuade women from opting for these careers although the proportion of women in STEM careers is increasing gradually,

Click here for HE Student Enrolments and Personal Characteristics 2016/17 - 2020/21. Females continue to be more likely than males to enrol for Higher Education Courses. Some students self- identify as "Other" rather than male or female

Click here for HE Enrolments by Subject Area and Sex. The gender differences in subject choice which occur at Advanced Level continue in Higher Education.

Click here for Women and Stem

|

- The Relative Improvement of Female Educational Achievement: A Checklist

- Change in the occupational structure.

- The increased employment of married women since 1945 and their significance as role models.

- Changes in socialisation within families

- Uncertainty around the likelihood or permanence of future marriage .

- Female infant and primary school teachers as female role models.

- The Equal Pay Act[1970] and the Sex Discrimination Act [1975]

- The gradual influence of feminist ideas throughout society.

- Changes in the social construction of femininity.

- Changing perceptions of family, career and education

- Feminist criticisms of the wider society and of the education system and feminist proposals for change

- Changes within the formal educational system: National Curriculum, GCSE, Course Work, Teaching Materials and Methods, GIST and WISE, Careers Advice, League Tables.

- Increased emphasis on equality of opportunity in political discourse and greater emphasis within schools on Equal Opportunities issues.

- Positive labelling of female students with possibly negative consequences for boys

- The increased visibility of positive female role models.

- Recognition that not all female students are educationally successful and consideration of the reasons for female underachievement in education.

Remember that not all girls are successful in education and that it is important to analyse interrelationships between gender, social class, ethnicity and educational achievement. Working class girls attainment levels are on average considerably lower than the attainment levels of middle class because working class girls may experience a range of material disadvantages and also because they may be more likely to engage in the kinds of anti-school behaviour which have more usually been associated with working class boys and because they may be negatively labelled in school. Click here for some information on Lads and Ladettes in School [Dr. Carolyn Jackson 2006] which addresses this phenomenon. Also click here for a brief video clip.

Click here for Interview with Professor Carolyn Jackson on Lads and Ladettes and related matters MAY 2020

In addition it is becoming clear that many girls may be subject to totally unacceptable levels of sexist bullying in schools and this could be a significant factor which, despite all of the positive developments mentioned above, may be undermining girls' prospects significantly. Click here for an item from the Revise Sociology site which provides some information on some of the different types of Feminism and addresses the issue of sexist bullying.

Click here for Professor Gillian Richards' more recent article on the lives of working class girls in which she argues that for a variety of reasons the career aspirations of some working class girls may remain limited . NEW link added April 2018

For Next Section Part 4 of 5: ( Part Four) - Click Here