Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Section Three: Essay "Race", Ethnicity and Educational Achievement

Please note: that I have currently written 7 essays on the Sociology of Education and intent to write a few more in the near future. Note that in each case these essays are far longer than could be written under examination conditions and that although they include points of knowledge , application and evaluation I tend to use separate paragraphs for each of these categories rather than to combine several categories in each paragraph as in the strongly recommended PEEEL approach whereby each paragraph should included Point; Explanation, Example: Evaluation and Link to following Paragraph.

I hope that you find the information in these essays useful but would strongly recommend that you write your own essays using the PEEEL approach or something very similar to it. Obviously your teachers will advise you as to appropriate essay writing technique.

Race", Ethnicity and Educational Achievement

The February 2023 version of the essay is divided into 7 Parts. It is now rather long but I hope students will be able to switch between the seven parts of the essay to extract the information they require.

Part One: Introduction

Part Two: IQ Theory

Part Three: Ethnicity, Social Class, and Material Circumstances

Part Four: Ethnicity and Subculture: Family Life, Language and Youth Culture

Part Five: School Organisation

Part Five B: The interaction of external and internal factors

Part Six: Ethnicity , Social Class and Educational Achievement : Ongoing Controversies 2014-2023

Part Seven: Conclusions

Part One: Introduction

Click here for Panorama “Let’s talk about race 2021.

Click here for BBC Drama series Small Axe: “Vivid stories of hard=won victories in the face of racism.”

Click here for a PowerPoint on “Race”, Ethnicity and Educational Achievement.

Before analysing trends in ethnic educational achievement, it is important to clarify the distinction between the concepts of "race" and ethnicity. In many Sociology textbooks the term "race" appears in inverted commas because sociologists and many others are sceptical as to the validity of the term. "Racial" differences refer to supposed biological differences between individuals such as differences in skin colour, hair texture or shape of eyes or noses and it has in the past been alleged that these biological differences are correlated with differences in intellectual or cultural characteristics suggesting the cultural and intellectual superiority of the white "race" over all other "races”. However geneticists have shown that real genetic differences between so-called biological "races" are extremely limited such that ,for example, it is entirely possible that if two black persons and one white person are chosen at random there may be more genetic similarities between one of the black persons and the white person than between the two black persons although many geneticists may still argue that the genetic differences which exist between different races are sufficient to make race a meaningful scientific term although they agree very strongly that ideas of racial superiority have been exposed as sickening but nevertheless dangerous myths . Sociologists therefore aim to investigate ethnic cultural rather than "racial" biological differences in educational achievement.

I have presented a detailed summary of official statistics on ethnic patterns of educational achievement in Part Two of the teaching notes on “Race, Ethnicity and Educational Achievement. In summary the official statistics document patterns of ethnic educational attainment from school readiness at ages 4-5 to access to higher education and degree classification. For many years and at all educational levels Chinese and Indian students have outperformed students from all other ethnic groups. The White Category contains White Irish students who perform well, White British students who are numerically by far the most significant White category, Gypsy Roma, Travellers of Irish Heritage, and other White students. Within the White category White British students have traditionally outperformed Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Afro-Caribbean students.

However more recent statistics on GCSE attainment indicate that patterns of ethnic educational attainment at GCSE Level have changed significantly. You may click here for data on Ethnicity and attainment at Key Stage 4 in 2018/19- 2021/22.

- Chinese and Indian pupils' attainment levels have continued to improve at a faster rate than those of White British pupils. You may click here for a summary of research by Louise Archer and Becky Francis analysing the high attainment levels of Chinese pupils

- Bangladeshi pupils have in recent years overtaken White British pupils.

- Black African pupils have in recent years overtaken White British pupils. However, there are significant variations in educational attainment within the Black African category.

- Pakistani pupils also now outperform White British pupils on some measures of Key Stage 4 attainment and in terms of their access to university although not to high status universities.

- Although White British pupils still reach higher attainment levels than Black Caribbean pupils this attainment gap has narrowed significantly. Black Caribbean pupils are more likely than White British pupils to gain access to Higher Education. Black Caribbean pupils eligible for FSM are more likely than White British pupils eligible for FSM to gain access to high status universities but in the case of NFSM pupils the reverse is the case.

- Unfortunately, however the attainment levels of Gypsy Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage pupils are far lower than pupils in all other ethnic groups.

- The statistics also document ethnic educational attainment by gender and free school meal eligibility.

- Females are shown to outperform males in all ethnic groups.

- “Other” pupils” [ i.e., those not claiming free school meals] outperform pupils eligible for free school meals in every ethnic group.

- Upper and middle class students outperform working class student in every ethnic group.

- For all pupils combined the FSM eligibility gap in attainment is greater than the gender gap in attainment but this is not the case for every ethnic group at every educational stage [ see for example, the Key Stage 2 data in Part Two of these teaching notes].

- Also, Free school meal eligibility gaps are considerably higher for White pupils than for pupils in other ethnic groups and sociologists continue to investigate the causes of relatively low educational attainment of free school meal eligible white pupils [ and particularly white boys] by comparison with the educational attainments of free school meal eligible pupils in other ethnic groups.

- It is also very important to consider ethnic differences in achievement at Advanced Level and ethnic patterns of enrolment in Higher Education. Data on these issues is provided in Part Two but you may click here for data on High A Level Grade Attainment and click here and here to access the data on relationships between ethnicity, gender, free school meal eligibility and access to Higher Education and access to Higher Education at High Tariff universities

- You may click here for recent data on ethnicity and degree classification. The data refer only to broad ethnic categories and the bracketed percentages refer to the percentages of graduates in each ethnic category who were awarded First Class Degrees : Asian [33.3%]; Black [20.0%]; Mixed[ 35.6%];White[39.4%] ; Other [30.8%].

Several explanations were advanced to explain the relatively poor performance of Black, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Gypsy Roma, and Traveller of Irish Heritage students. However Chinese and Indian students have for many years out-performed White British students and in recent years Bangladeshi students and Black African students have overtaken White British students as have Pakistani students on some measures of Key Stage 4 attainment while Black Caribbean students are beginning to catch up White British students. Therefore, we must now recognise that although Black and Minority Ethnic pupils continue to face some educational disadvantages in the education system, they are beginning to surmount them, and increasing attention has been given to the educational problems faced by White British pupils [and particularly White British working class pupils] within the education system.

Part Two: IQ Theory

It has sometimes been argued that the relatively poor performance of some ethnic minority students can be explained in terms of their lower mainly genetically inherited intelligence but sociologists are generally critical of this view .Thus they point out that. it may be impossible to define exactly what ""Intelligence" is; IQ tests may be culturally biased; they may not measure "Intelligence" but simply the ability to do IQ tests; individuals’ IQ test results depend upon whether they were nervous when taking the test and on how seriously they have taken the tests ; that even if it could be shown that individual intelligence is to some extent inherited this would not prove that , for example, Asians as an ethnic group had inherited greater intelligence than Whites as an ethnic group; that IQ test scores depend upon a range of economic, cultural environmental factors and that with the current state of knowledge it is not possible to assess the relative importance of heredity and the environment as factors influencing Intelligence.

We may note also that Blacks' IQ test scores have increased relatively quickly in the USA since the introduction of Civil Rights reforms and in South Africa since the ending of Apartheid and that if current trends continue it will not be long before Blacks' IQ scores surpass Whites' IQ scores; that American East Asians currently outscore both American Whites and American Blacks ; and that given the "racial" similarities between Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis it is surely nonsensical to explain differences in educational achievement among these groups in terms of racially inherited differences in IQ. In any case in England Chinese and Indian students have long outperformed White British students at GCSE Level; Bangladeshi pupils have overtaken White British pupils in recent years and the performance gap between Pakistani students and White British students and between Black and White British students are narrowing.

Further information on IQ Theory is provided below.

The comparison of IQ test scores of members of different ethnic groups has occurred more frequently in the USA than in the UK and in the USA the available data suggest that Americans of Asian origin typically score slightly higher in IQ tests than White Americans who in turn have typically scored 10% -15% higher than Black Americans although the gap between White American and Black American test scores is narrowing.

Supporters of IQ Theory such as Arthur Jensen, Hans Eysenck, Richard Herrnstein, and Charles Murray make the following claims:

- Intelligence can be clearly defined.

- Intelligence, once defined, can be measured accurately in IQ tests.

- Between 40% and 80% of the variation in intelligence between individuals can be explained by genetic factors.

- Average differences in intelligence between upper, middle and working class people can be explained to a considerable extent by genetic factors although the precise significance of heredity and environment in this respect cannot be known with certainty.

- Genetic factors help also explain differences in intelligence between ethnic groups although once again the relative importance of genetic and environmental factors cannot be known with certainty.

- However, in "The Bell Curve" [1994] Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray suggest that it may be reasonable to assume that 60% of the variation in intelligence between Black and White Americans may be explained by genetic factors.

[Charles Murray also developed a theory of the "Underclass" in the USA in the 1980s which he explained the intergenerational persistence of mainly Black and Hispanic poverty partly in terms of the fatalism and lack of ambition of Blacks and Hispanics which he believed to have been caused by their excessive reliance on generous welfare benefits which creates a "culture of dependency" from which they cannot escape. In The Bell Curve Murray and Herrnstein suggest that Black poverty may result also from the lower inherited IQ of black people. and their ideas have been seized upon by the supporters of the "New Right" who argue that since poverty is to be explained mainly or at least partly by genetically inherited low IQ , increased government spending on social security and education will be unlikely to solve the problem. However, IQ theory in general and The Bell Curve in particular have also attracted several criticisms]

Many sociologists are critical of arguments that differences in intelligence can be accurately measured by IQ tests and that differences in IQ test scores between Blacks and Whites can be explained to a significant extent by differences between Blacks and Whites in their genetic inheritance of intelligence.

With regard to the limitations of IQ tests sociologists point out that::

- It is difficult to define what "Intelligence " actually is although Eysenck and Jensen have defined it as "abstract reasoning ability."

- It is open to question whether so called Intelligence Tests or IQ tests can accurately measure current intelligence or the potential to increase one's intelligence in the future. The fact that one can quickly improve one's test scores with a little practice suggests that these tests are unlikely to measure our fundamental intelligence or our potential to develop our intelligence in the future.

- These tests may be culturally biased in various ways as where they demand knowledge more likely to be available to white [and middle class] respondents

- Related to the above point such tests may therefore be may be testing knowledge rather than intelligence.

- Test results are likely to vary according to the conditions surrounding the test. In racist societies the self-confidence of ethnic minority members may have been systematically undermined so that they under-perform in IQ tests much as they have sometimes done in the education system more generally.

- More straightforwardly the tests results may fail to accurately measure intelligence because some respondents may be nervous, unwell or may not take the test seriously.

Let us now consider the arguments that claims that differences in IQ test scores between Blacks and Whites can be explained to a significant extent by differences between Blacks and Whites in their genetic inheritance of intelligence.

- Herrnstein claimed in the late 1960s that between 40% and 80% of the differences in IQ scores between individuals could be explained by inherited differences in intelligence. The relative importance of heredity and environment as determinants of intelligence may be estimated in a variety of ways most notably via the study of separated identical twins reared in different environments such that any observed similarity in IQ tests scores might be explained more reasonably by the similar genetic endowments of the twins than by environmental factors which would be different in the case of each separated twin. However, critics of Herrnstein such as Leon Kamin have pointed out that the separated twins were often reared in similar environments and indeed in different branches of the same family so that the observed similarities in IQ test scores could be explained much more by environmental factors than suggested by Herrnstein. Kamin further claims that a careful analysis of other types of study designed to isolate genetic and environmental influences on IQ test scores suggest that environmental influences are far greater and genetic influences far smaller than is suggested by Herrnstein.

- In The Bell Curve [1994] Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray do not of course wish to argue that differences in IQ test scores are determined entirely by genetic factors. Thus they state that " the debate about whether and how much genes and environment have to do with ethnic differences remains unresolved" but having made this statement they quickly re -iterate, [despite the criticisms of Kamin and others] the original Herrnstein estimates that hereditability explained between 40% and 80% of individual differences in IQ test scores [and hence, according to them, in intelligence ] so that it might be reasonable to assume that a mid-point figure that of 60% of the difference in IQ test scores between Blacks and Whites might be explained by differences in inherited intelligence between Blacks and Whites.

- When critics claimed that the differences in IQ test scores could be explained by the higher average socio-economic status [i.e. social class position] of Whites which meant, for example, that Whites, on average, had more years of schooling than Blacks , Herrnstein and Murray rejected these criticisms on the grounds that Whites were shown to achieve higher IQ test scores than Blacks even when the test scores of Blacks and Whites in the same social class position were compared.

- Herrnstein and Murray also rejected all the potential criticisms of IQ tests which I have outlined above.

Not surprisingly The Bell Curve has attracted massive criticisms including the following.

- It is pointed out [as was mentioned early in the previous Unit] that overall variations between "racial" groups are far smaller than variations between "racial" groups leading many to claim that the concept of "race" has no scientific validity or usefulness or at least that such small differences between races as do exist are highly unlikely to result in differences in intelligence.

- It is pointed out that no intelligence gene has so far been discovered so that the strength or weakness of genetic influence on intelligence must be a matter of speculation. Acknowledged expert sociologist and geneticist respectively Christopher Jencks and Steve Jones both state that the relative influences of heredity and environment on intelligence are currently unknown and even probably unknowable. May it not be just as possible that Black Americans have inherited greater intelligence than White Americans rather than vice versa?

- It is pointed out that in the USA there has been considerable intermarriage between Black and White individuals so that many "Black" and "White" Americans might more accurately be described as of "Mixed Race."

- Although Herrnstein and subsequently Herrnstein and Murray have claimed that because there are differences in IQ test scores between Blacks and Whites in all social classes this indicates a limited environmental effect on intelligence , we may note that in 1972 Bodmer had pointed out that over two hundred years of prejudice and discrimination in the USA against black people prevents an equalisation of the environment with whites and this undermines the validity of the Herrnstein comparison of IQ test results because even if it is possible to control for the effects of membership of different social classes it is impossible to control for the adverse effects of racism which is likely to affect blacks in all social classes. It is difficult to see how Jensen and Eysenck could make valid comparisons between black and white people in racist societies because even when they attempted to compare blacks and whites from the same social classes these groups might have similar incomes but black people would still be socially disadvantaged as result of the effects of racism. Identical criticisms were made in the USA of Herrnstein and Murray almost immediately after the publication of The Bell Curve.

- There is considerable evidence that environmental influences on the relative IQ test scores of Blacks and Whites are considerable.

- The higher IQ test scores of Northern relative to Southern Blacks in the USA for much of the 20th Century may be explained partly by the greater levels of discrimination faced by Southern Blacks.

- Researchers such as James Flynn have pointed out that IQ test scores are rising on average at the rate of 3% per decade and that in the USA, for example, Black and White IQ scores have been rising at annual rates of 0.3% and 0.45% respectively which means that in perhaps another 40-50 years Black scores will have overtaken white scores. [James Flynn was interviewed as part of the recent Documentary for Channel 4 by Rageh Omaar: "Race" Science's Last Taboo

- Such rapid increases in IQ scores cannot possibly be explained via genetic evolution which occurs only very gradually but can certainly be linked to environmental factors such as improvements in health, housing, and education.

Most of the above discussion surrounds the analysis of differences in IQ test scores between Black and White Americans. Comparisons of ethnic differences in IQ test scores have rarely been made in the UK but the Swann Committee Report [Education for All 1985] did attempt to investigate the possible strength of environmental influences on IQ test scores and came to the conclusion that ethnic differences in IQ were insignificant once environmental factors were taken account of. Furthermore we now find that students in all ethnic minority groups are more likely than white students to enrol on undergraduate degree courses which hardly suggests that members of ethnic minority groups are on average genetically less intelligent than white people.

| Activity 1. Re-read the information on Intelligence, IQ tests and their limitations. To what extent do you accept or reject the conclusions of IQ theory in relation to the educational achievements of different ethnic groups? Give reasons for your answer. |

Part Three: Ethnicity, Social Class and Material Circumstances

When ethnic minority students do underachieve in education this may be explained partly by social class disadvantages and partly by educational disadvantages related specifically to their ethnicity.

Click here for a table which indicates that there is very significant ethnic variation in eligibility for free school meals.

It follows that because ethnic minority members are disproportionately likely to experience poverty, they are in effect experiencing class disadvantages which are also made more likely because they are more likely than white people to be in the lower sections of the working class partly because of the effects of racial discrimination. Ethnic minority students from poor backgrounds may have poorer diet causing lack of energy, concentration difficulties and illness leading to absence from school. They may be forced to miss school to look after sick siblings if their parents cannot afford to take time off work; they may not have a quiet comfortable study room; they may be forced to take part-time jobs which reduces the time available for study; their parents may be unable to afford books, computers, expensive school trips and private tuition. Poorer students are more likely to live in deprived areas and to attend relatively ineffective State schools which gain relatively poor examination results and moving to more affluent areas with more effective State schools or the choice of successful but expensive Private schools will not be possible for them. Also, the possible financial sacrifices associated with higher education may be especially alarming and this may prevent talented ethnic minority children from poor families from entering Higher Education.

BAME families may be more likely to experience poverty and deprivation for a variety of reasons but it is also the case that BAME pupils eligible for Free School Meals outperform White British Pupils eligible for Free School Meals so that although poverty may well inhibit the educational attainment of many BAME pupils they appear to be able to offset the effects of poverty more effectively than White British pupils although this does not mean that the adverse effects of poverty are insignificant for many BAME pupils. Were it not for their poverty they might do even better.

Click here for variation GCSE results by ethnicity and free school meal eligibility2020/21 {Ethnicity: Facts and Figures]

Click here for Child Poverty and education outcomes by ethnicity [2020] . A detailed ONS article.

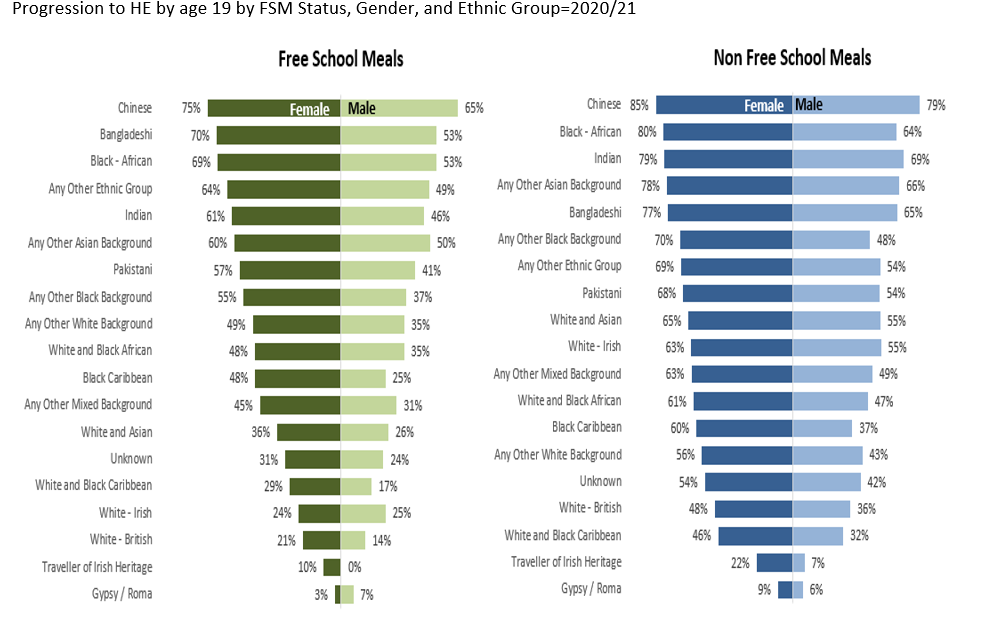

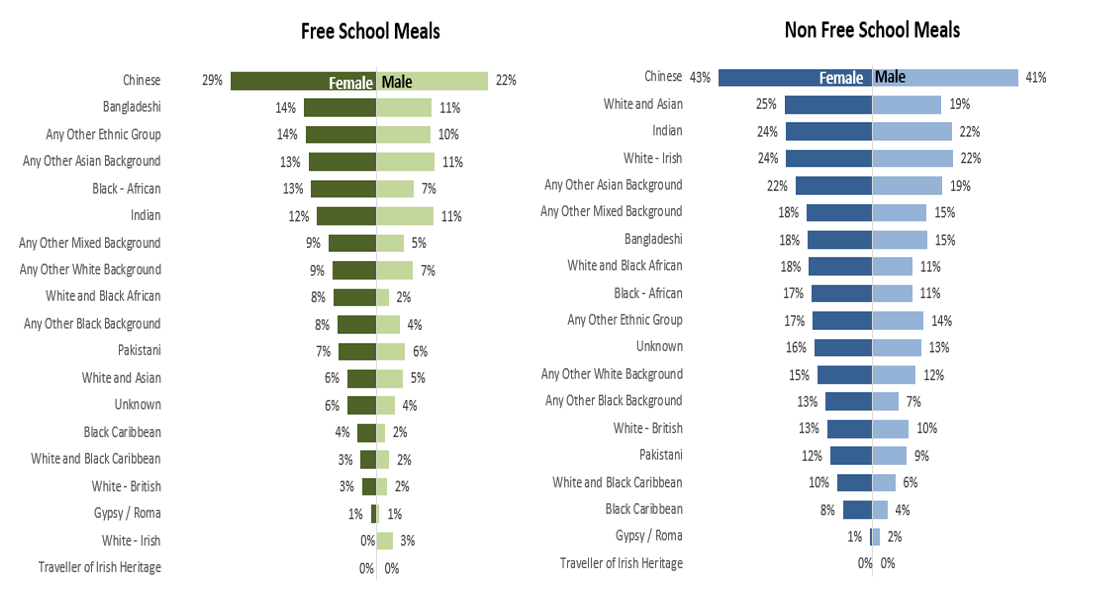

Click here for Widening participation in higher education 2022. You may then scroll down to Explore data and files and then to Free School Meals, Gender and Ethnic Group for detailed data on Progression to HE by age 19 by FSM Status, Gender and Ethnic Group-2020/21. Notice that there are also variations in the patterns of access to HE in general and access to high status HE.

You may also click here and here for direct links to the relevant statistics and I have copied the relevant diagrams here

Progression to HE by age 19 by FSMS tatus, Gender and Ethnic Group-2021

Progression to high tariff HE by age 19 by FSM status, Gender and Ethnic Group

The Colour of Class: The Educational strategies of the Black Middle Classes: Nicola Rollock, David Gillborn, Carol Vincent, and Stephen J. Ball

The above data indicate that ethnic minority pupils are more likely than white pupils to experience poverty and economic disadvantage and that this impacts adversely on their educational prospects but in The Colour of Class the authors illustrate that upper middle and middle Afro-Caribbean parents may also experience racial prejudice and discrimination in their dealings with the British education system which may impact adversely on the children’s education progress. You may click here for a summary of this study.

Part Four: Ethnicity and Subculture: Language, Family Life, Language and Youth Culture

Family Life

Sociologists have also considered how ethnic minority family life might affect educational attainments. Writing in 1979 Ken Pryce argued that Afro-Caribbean students might to some extent be disadvantaged by their family characteristics and later writers have emphasised the large proportion of single parent families among Afro -Caribbeans. Against this it has also been claimed that Afro-Caribbean single parents are often resilient, receive considerable help from [often female ] wider kin and often take their children's' education very seriously and also that even when Afro-Caribbean fathers do not live in the same household as their partner/ children they continue to participate considerably in the upbringing of their child/ children.

Click here and scroll down a little for data on the Ethnic Group of Lone Parents.

Given the size of the White population in the UK it is clear that the vast majority of lone parent families are white. However in percentage terms it is true that lone parenthood is most likely in black families but there is no necessary reason why lone parents, whatever their ethnicity should prove to be less effective parents although they may in some cases be more likely to experience poverty which may impose considerable financial constraints on them and their children.

Click here for a TV discussion and here for a recent Guardian article of the issues around the roles of black fathers.

Click here an article on Black Families by Tracey Reynolds responding to an article by Tony Sewell

There are several studies [such as Driver and Ballard1981 and Ghazala Bhatti [1999] which suggest that Asian parents [Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi] do see their children's education as very important and both Afro-Caribbean and Asian parents are more successful than white working class parents in encouraging their children to stay on in school after post-compulsory education. You may also click here and here for direct links to the relevant statistics on ethnicity and access to Higher Education.

Further evidence of ethnic minority parental interest in their children's education is shown by telephone poll data reported in the recent 2005 DfES study which reported that based on a telephone survey of approximately 1500 ethnic minority parents or carers that they were more likely than a representative sample of the whole UK population to feel very involved in their children's education and more likely to see parents as mainly responsible for their children's education. In addition 82% of ethnic minority parents/carers were likely to attend parents evenings at every opportunity and 40% stated that they were always confident helping children with homework although the figures were a little lower in the case of Pakistanis[36%], Bangladeshis[34%] and those for whom English was not their first language[34%]. We may note also that in some cases where ethnic minority students have been relatively unsuccessful in education their parents have shown themselves ready to organise special weekend schools in an attempt to raise their achievements again pointing to very high levels of parental interest.

Further information on ethnicity, family life and educational attainment

You may click here for a detailed DFE Report: A Compendium of Evidence on Ethnic Minority Resilience to the Effects of Deprivation on Attainment . Pages 17-25 of this Report contain useful information on possible reasons for ethnic differences in attainment among pupils eligible for free school meals.

In this Report the authors summarise some of the available research studies which aim to assess the relative importance of school factors, and parental and student attitudes as determinants of the trends in ethnicity, free school meal eligibility and student attainments. Detailed evidence is provided to suggest that ethnic differences in parental and pupil attitudes help to explain ethnic differences in pupil attainment.

- They note that Professor Steven Strand has found that parental attitudes and behaviours were significantly related to pupils' educational attainments at age 16. Thus "on average Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Indian and Mixed Heritage parents were more likely than White British Parents to have higher educational aspirations, to have paid for private tuition, to know where their children were when out, to have greater involvement with their children's school, were less likely to quarrel with their child and were less likely to be single." According to Professor Strand these factors helped to explain the attainment gap between White working class pupils and ethnic minority pupils of similar socio-economic status.

- However, Professor Strand notes that although Black parents shared many of these characteristics with other Ethnic Minority parents their children were less likely to do well in school and Professor Strand attributes this tentatively to some combination of low teacher expectations, racism within schools and peer group effects.

- Professor Strand's conclusions are supported by research from Demie and Lewis based [ 2011] on interviews and focus groups with school leaders, class teachers, teaching assistants, governors, parents, and pupils in 14 schools in one London LEA. Thus, they note that head teachers and class teachers perceived white working class parents as having low educational aspirations for their children perhaps because they were more likely to be young, because they had little belief in the value of school and because they lived in areas of high unemployment which generated a culture where "pupils felt it not necessary to worry about doing well in school." Consequently, this led to a range of problems including pupil absence, lateness, willingness of parents to tolerate poor behaviour and parental failure to take up opportunities for parental involvement in family improvement and parenting skills and after school clubs. By contrast working class ethnic minority parents were perceived as more interested and involved in their children's education. However, notice that this conclusion is about teachers' perceptions of white working class parents which may or may not be accurate.

- Professor Strand also investigated pupils 'attitudes and risk factors. Here he found that ethnic minority/free school meal pupils scored higher than White British/ free school meals pupils on aspiration, future planning, attitudes to school, academic self-concept and time spent completing homework and that White British/free school meal pupils had higher risk factors in terms of SEN eligibility, truancy, absence, and problems leading to the involvement of the police and social services agencies.

- The Report's authors conclude that available evidence suggests that differences in attainment related to ethnicity and free school meal eligibility are more dependent upon parents' and pupils' attitudes and values than on school-based factors.

- However, the Report states also that further research on the effects of aspirations is necessary as is indicated in the following long quotation. "It is frequently asserted that ethnic minority parents have high aspirations for their children while white working class parents do not. However, research evidence on the place of educational aspirations as a factor explaining differences in attainment is inconclusive. Educational aspiration is difficult to measure and to disentangle from lack of awareness of opportunities to which pupils and their parents can aspire. Further research is needed on whether it is low aspiration which leads to underachievement of white working class pupils or other barriers such as knowledge of opportunities or lack of resources to promote literacy."

- These are very important conclusions which are often referenced in other reports and, for what it is worth, I would recommend highly that students click here for this detailed DFE Report: A Compendium of Evidence on Ethnic Minority Resilience to the Effects of Deprivation on Attainment and read pages 17-25 which contain useful information on possible reasons for ethnic differences in attainment among pupils eligible for free school meals. It won’t take long!!

- It should be remembered that theories based around the alleged cultural deprivation of working class students and their families have a long history in Sociology and that they have been subjected to several significant criticisms. Further information on these theories can be found here and more detailed information can be found here.

- Bourdieu’s theories suggest that some working class students underachieve not because they and their families are in some respects lacking in "aspiration" or because they lack the cultural, social and economic capital necessary to translate their aspirations into effective strategies to improve their educational attainment levels.

- . Also, very importantly some sociologists have argued that in any case the concept of "aspiration" requires further analysis in that if many working class students aspire to traditional working class jobs located within their own working class communities rather than to usually relatively short range upward social mobility into not necessarily fulfilling routine lower middle class jobs this should not be defined simply as a "lack of aspiration".

Click here and here for a thought provoking articles by Garth Stahl on the nature of white working class aspiration and click here for an article by Prof. Tony Sewell and click here for further comments from Garth Stahl. The differing emphases of these articles may generate useful discussion.

Language

It has been argued that ethnic minority students may face a range of linguistic disadvantages which undermine their educational prospects. They may be disadvantaged because in some Asian households English is not the first Language and some Afro Caribbean origin people may speak and write in Creole or Patois which are non- standard English dialects, the use of which may inhibit their understanding of more formal English. However there is considerable dispute as to the importance of language and several studies such as those of Driver and Ballard [1981] and the Swann Report [1985] suggested that initial language difficulties had mostly been overcome by the age of 16 while the Policy Studies Institute Fourth National Survey of Ethnic Minorities (Modood et al 1997) suggested that it was mainly older ethnic minority people who often did have significant language difficulties.

The issue of language has also be linked with the issue of so-called negative self-images among ethnic minority students. It has been suggested that if West Indian origin students consistently speak and write in Creole and this is consistently graded as incorrect by teachers, this could result in these students generating a negative self-image which would restrict their overall progress although of course this is not the only process which could generate negative self-images. Attempts have been made to assess the self-image of ethnic minority students using so -called "doll studies" where students are shown black and white dolls and asked which they prefer and the relative preference of ethnic minority children for white dolls is taken as evidence suggesting that some ethnic minority students do indeed have a "negative self-image". However, and not surprisingly, several critics have warned against drawing too clear conclusions from these studies: many ethnic minority children clearly have very positive self-images which are encouraged by ethnic minority parents.

Recent research published by the DfES in 2005 suggested that although language difficulties may affect some ethnic minority pupils quite significantly in the early stages of their education, the adverse effects of language disadvantage declines significantly by the age of 15-16 and. indeed in 2016=17 students for whom English is a second language on average performed slightly better at GCSE level than other students for whom English is a first language. This trend has continued in recent years.

Important addition [1] February 2023

Significant research is currently being conducted by Ian Cushing on the various ways in which the educational progress of Black pupils may be being undermined because linguistic competence is being assessed more in terms of breadth of vocabulary and conventional grammatical competence than in terms of the vibrancy and originality of Black pupils’ use of language. Click here for a Guardian on issue of verbal deficiency which reports that:

A survey of 1,300 primary and secondary school teachers across the UK found that more than 60% saw increasing incidents of underdeveloped vocabulary among pupils of all ages, leading to lower self-esteem, negative behaviour and in some cases greater difficulties in making friends.

However, Ian Cushing argues that measuring linguistic competence in terms of a word gap underestimates the linguistic competence of Afro-Caribbean children and more broadly that when black relative educational underachievement is explained in terms of the existence of a linguistic deficit this deflects attention from what he sees as the far more significant effects of structural racial inequality on educational attainment. You may click here for a recent video lecture by Ian Cushing in which he describes in some detail the inadequacies of linguistic deficit models as explanations of ethnic educational inequality. In so doing he also references some of the studies which are covered in Advanced Level Sociology textbooks.

Click here for a recent article by Ian Cushing in The Conversation in which he discusses these issues

Important addition [2] February 2023

The work of Dr April-Baker Bell similarly focuses upon the vibrancy of Black American language and hence to encourage and support students in the use of their own language.

New Sources with thanks to Fran Nantongwe

Click here for important current thinking on language and ethnicity from Dr April Baker-Bell

Click here for a Webinar presentation by Dr Baker Bell

Click here for information about Dr April-Baker Bell’s new book Linguistic Justice Black Language, Literacy, Identity and Pedagogy

Important addition [3] February 2023

Click here and then on Key stage 4 performance 2022 and then on the Attainment by first language status link for the most recent information on differences in educational attainment at Key Stage 4 between pupils for whom English is and is not their first language. The Report concludes that.

“In 2018/19, 2020/21 and 2021/22 pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) have had slightly better attainment than pupils with English as their first language (Non EAL) across all the headline measures.”

Click here for a table illustrating the higher attainments at GCSE level of students for whom English is an additional language.

Click here for Widening participation in higher education 2020/21. Scroll down to Explore data and files and then to the First Language link. Alternatively, you may click here for a direct link to the relevant data. On Progression to Higher Education the report concludes:

A majority of pupils with a first language other than English progress to HE by age 19. 59.2% of pupils with a first language other than English progressed to HE by age 19 by 2020/21 compared to 41.6% of pupils with English as a first language. The progression rates have increased by 8.4 percentage points and 9.4 percentage points respectively since 2009/10.

However in a detailed recent article entitled The Educational Achievement of Black African Children in England[2021] Feyisa Demie notes the great linguistic diversity of Black African students for whom English is an additional language and that GCSE attainments of African students vary considerably depending upon the African language spoken at home. Thus, Feyisa Demie’s data [see pp 9-11 of his article] which refer to an Inner London Local Authority show that in 2019 100% of African students who spoke the Ga language at home gained 5 or more GCSE Grades A*-C including English and Mathematics but only 40% if students speaking the Krio Language at home did so. Also, among White students for whom English is an additional language, language diversity is also considerable. Thus, even if students for whom English is an additional language are on average doing well this certainly does not apply to all linguistic subgroupings.

Youth Culture

There has been a veritable parade since the end of the Second World War of mainly White youth subcultures differentiated according to their tastes in fashion and music but also, to some extent, according to the attitudes and values of their members. Discussion of the appearance, behaviour and attitudes of successive waves of Teddy Boys, Mods, Rockers, Hippies, Punks and Goths has often pre-occupied certain sections of the mass media and that section of the Sociology profession specialising in the analysis of "youth subcultures." Furthermore, sociologists specialising in educational issues have explained the relative educational underachievement of white working class boys not necessarily in terms of their subcultural styles, but at least partly in terms of the development of an anti-school pupil subculture which is thought to arise partly out of the general condition of working class life but also as a response to processes such as streaming, banding and setting operative in the schools themselves.

More recently, while relatively little attention has been given to the youth subcultures which may among Chinese, Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani pupils, it has been argued that certain aspects of youth subculture operative among Afro-Caribbean boys may help to explain their relative educational under -achievement. Perhaps the best known study of Afro- Caribbean youth subculture in the UK has been provided by Tony Sewell in "Black Masculinities and Schooling" [1997], which is based upon an investigation of Afro-Caribbean boys in a boys only 11-16 comprehensive school. Sewell distinguishes between four main responses among Afro-Caribbean boy to education which he terms conformity, innovation, retreatism and rebellion.

Thus 41% of the Afro-Caribbean pupils in the sample are described as "Conformists" who accept school rules and regulations and are ambitious for educational success; 35% are "Innovators" who are also ambitious for educational success but they are critical of school rules and regulations and distance themselves from both teachers and conformist teachers because they wish to be educationally successful but on their own terms; there are a small proportion [6%] of "Retreatists" [often pupils who have been defined as educationally subnormal] who aim simply to keep a low profile and stay out of trouble but unfortunately are nevertheless unlikely to be successful; and finally Sewell describes 18% of the pupils as "Rebels" who identify closely with Black Macho street culture as portrayed especially in certain sections of the mass media and music industries, lack ambition and are likely to behave in confrontational ways which teachers believe reduce the prospects for effective class teaching and may represent a blatant challenge to teacher authority.

It is important to note that only 18% of these boys are classified as rebels in comparison with the 76% who are keen for educational success although admittedly 35% of the pupils pursue success in a way that some teachers might regard as "unorthodox" . In relation to the "Rebels" it is possible that in some cases these boys’ youthful self-confidence may provoke negative over-reactions by teachers who may have misinterpreted their behaviour as confrontational and threatening. Also, if these boys do show anger within the school environment, such anger may be understandable given their experiences of racism and blocked opportunities in the wider society and of what they perceive to be discriminatory setting procedures and excessive rates of school exclusion relative to boys in other ethnic groups [especially white boys] who can be just as disruptive but are less likely to be excluded.

Tony Sewell's study has been criticised in some quarters for its alleged excessive emphasis on rebellious youth subculture as an explanation of relative educational achievement among Afro-Caribbean origin boys. However, although he does indeed focus on the rebelliousness of some Afro-Caribbean origin boys Tony Sewell does also describe the teacher racism [sometimes unintended] and generally poor teaching which the pupils receive in many but not all classes as well as the extent to which teacher-pupil confrontations arise partly as a result of rebellious pupil behaviour but also partly as a result of teachers' misinterpretation of this behaviour. Other analysts do, however focus more than Tony Sewell on the impact of poverty and/or of school organisation and less than Tony Sewell on aspects of Afro-Caribbean youth culture.

Click here for a recent article by Tony Sewell and click here for a profile of Tony Sewell.

Tony Sewell was appointed Chairperson of The Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities {CRED} which published its Report March 2021. The Report is very wide ranging and I shall only summarise here its main conclusions on the education of Ethnic minority students

- The Report emphasised that ethnic minority students are making good educational progress and that only Black Caribbean, Gypsy Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage pupils are performing worse than White pupils. {It should be noted, however, that although Black African pupils are on average performing well, some subgroups within the Black African category are less successful than others.]

- It did not deny the existence of institutional racism in the UK but argued that the term should be used with much more care than was currently the case [according to the authors of the Report]. The authors argue that the relatively poor performance of some ethnic minority students can be explained not just in in terms of their ethnicity but also in terms of their social class background, their gender and their geographical location so that to emphasise only the pupils’ ethnicity would be misguided.

- The authors also argue that because, on average, students in several ethnic minority groups have higher levels of attainment than White British students it means that racial discrimination is unlikely to be a very significant factor affecting educational achievement and that the fact that Black African students out- perform Black Afro-Caribbean students points to an absence of anti-Black racism.

- To explain ethnic differences in educational attainment the CRED suggested that ethnic differences ibn educational attainment can to some extent be explained in terms of the Immigrant Paradigm.

- This suggests that whereas white working class students may carry a legacy of several generations of educational underachievement and that the same may apply to Black Caribbean students whose families may have migrated to the UK in the 1950s Black African families may have arrived in the UK more recently and have retained their optimism as to the prospects of educational success. Also, Black African and Indian origin adults may be well educated and have held professional jobs in their country of origin which are more likely to foster beliefs in the possibility of upward social mobility. It is further suggested that Pakistani and Bangladeshi families are more likely than White working class families to be able to draw on community resources to promote educational success.

- It must be emphasised that this line of argument has been seriously called into question on the grounds that negative stereotypes of Afro-Caribbean culture have regularly been used to explain Afro-Caribbean underachievement in a way which marginalises the impact of material disadvantage and racism within schools and the wider society that many sociologists see as key factors in Afro-Caribbean underachievement.

- Having questioned the extent of institutional racism in general CRED also questioned its extent in the school system and while it recognises the higher rates of pupil exclusion of Black Caribbean pupils it denies that this can be explained in terms of institutional racism’

- The Report also downplays the significance of negative labelling as a factor inhibiting educational attainment. This flies in the face of a great deal of sociological research and recent reports for the IFS by Diane Reay and by Heidi Mirza And Ross Warwick certainly reiterate the continued significance of negative labelling.

- The Report emphasised that it was very important for ethnic minority histories and cultures to be represented positively within UK school and college curricula, but it also courted controversy because of its claims that students might face dangers of indoctrination by teachers sympathetic to the arguments of critical race theorists.

- The Report also attracted criticism because of its treatment of the history of slavery and minor amendments were made in the Report to address these criticisms. For this and further criticisms of the Report from the Guardian click here and for a defence of the Report by Kemi Badenoch click here and here for a more detailed statement of her views.

Ethnicity and Culture: Conclusions

With regard to family life it is noted that a large proportion of Afro Caribbean families are headed by lone mothers and that this might in principle affect their children’s educational prospects adversely although there are several studies which point to the resilience of Afro-Caribbean lone parent families and to the fact that non-resident fathers may nevertheless participate substantially in the upbringing of their children.

With regard to ethnic minority family life in general there were several studies from the 1980s to the early 2o00s which indicated that if anything Asian and Black parents on average took their children’s education very seriously and ethnic minority educational achievement levels now exceed white British educational achievement levels in all ethnic categories apart from the Black Afro-Caribbean , Gypsy Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage categories.

From around 2014 attention began to focus especially on the relative educational underachievement of white working class pupils [i.e. those eligible for free school meals] and it was suggested that minority parents and pupils were if anything more likely than white British parents and pupils to prioritise educational achievement although the difficulties of measuring and comparing aspirations and expectations with any certainty were recognised .

Many Asian, African and White children may have English as an additional language [EAL] but there is clear evidence that although these children may be at a disadvantage when they enter school by the age of 16 they are on average outperforming pupils whose main language is English and they are also more likely to gain access to Higher Education. However as noted above in the case of African pupils some linguistic subgroups within the broad ethnic categories mat continue to experience difficulties. Also it is argued that Afro-Caribbean pupils in the UK Black American pupils may face difficulties because their specific dialects are undervalued in school setting as is indicated in the work of Ian Cushing [UK] and April Baker-Bell [USA]..

The issue of Afro-Caribbean youth culture is considered to be a significant factor affecting educational achievement by Tony Sewell, but other sociologists claim that he has overstated its importance and underestimated the importance of material poverty and institutionalised racism within schools as factors affecting educational achievement.

Part Five: Ethnicity and School Organisation

Racism and Perceptions of Racism

Following the election of Barack Obama as President of the USA it was suggested that the USA might be evolving into a post=racial society in which the need for positive discrimination in favour of ethnic minorities would decline and government policies would become colour blind or race neutral. Such views are indeed accepted by many Americans [mostly White Republicans] but other Americans believe that believe that racial prejudice are still widespread. Also in the UK it is suggested that the extent of racism has declined in recent years and that such racism as does exist is now more subtle and covert. You may click here for recent data from Ipsos Mori indicating that the UK is now generally perceived as a less racist society but unsurprisingly perceptions of racism run high among young Black people as indicated here in the Young and Black Report produced by the YMCA. Click here for Panorama “Let’s talk about race [2021] which draws similar conclusions.

Personal, Structural and Institutional Racism

There are many studies which suggest that the academic attainments ethnic minority students are adversely affected by the racism which they experience within the UK education system and in the wider society , but it then becomes important to distinguish between the racism which may derive from the consciously racist attitudes and behaviour of individual teachers and the institutional racism which may arise out of the organisation of individual schools and/or from the organisation of the UK education system as a whole. Of course, there are disputes as to the extent to which individual and institutional racism exist within schools.

As has already been noted Chinese, Indian, Bangladeshi, and Black African students have for some time outperformed White British students and there is some evidence also that in most recent years Pakistani students also are beginning to overtake White British pupils. These trends are taken to suggest the relative absence of racism within schools while the fact that Black African students are performing well is taken to show that the slower progress of Afro-Caribbean students must be explained in terms of cultural factors rather than anti-Black racism.

However, these views are also contested. It is argued that Chinese and Indian pupils especially might be positively evaluated within schools as “model minorities” while at the same time Afro-Caribbean and indeed white working class pupils might be especially likely to be evaluated negatively and in their 2007 study Archer Becky Francis and Louise argued that even Chinese pupils were negatively evaluated relative to white middle class pupils who were deemed to approximate most closely to teachers’ notion of “the ideal pupil. Also, very unfortunately Afro-Caribbean and white working class pupils certainly were negatively evaluated. New link needed on 2007 study Chinese pupils

Louise Archer reiterates this point in a recent[2008] detailed academic study Louise Archer suggesting that "the normalised "ideal pupil" emerges as the dominant male, White, middle class Western subject. " Although Advanced Level Sociology students need not familiarise themselves with the details of this highly technical article they may scroll down to page 13 of the article and a table illustrating this conclusion which may provoke some class discussion

Negative evaluation by British teachers of Afro-Caribbean culture is confirmed in the recent study [2023[ by Derron Wallace. However, excellent studies as these are, they are also small scale studies and so cannot be assumed to be representative of the entire UK education system.

Individual, Structural and Institutional Racism: Definitions

Click here for an article from the Conversation by Professor Vini Lander

If due to his /her ethnicity and individual suffers verbal or physical attack this would be an act of individual racism. However if members of ethnic minority groups on average have poorer education and employment prospects, are less healthy and are discriminated against in the legal system then the structures of society are operating against their interests and they may be said to be subject to structural racism. experiencing structural racism. If a particular institution repeatedly operates to the disadvantage of ethnic minority groups that institution may be said to be institutionally racist.

In her study Race and Society [2017], Tina G. Patel points out that the term “Institutional Racism” originated in the 1967 work of Stokely Carmichael [later Kwame Touré] and Charles Hamilton in 1967where they stated that “ ...When in…Birmingham Alabama . 500 black babies die each year because of the lack of proper food, clothing shelter and proper medical facilities and thousands are destroyed or maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the black community, that is a function of institutional racism.”

However in his recent article Professor Vini Lander notes a distinction between structural racism and institutional racism and notes that while structural racism applies to the effects of the interconnected practices of a range of social institutions a specific application of the concept of institutional racism was provided in the Macpherson Report into the Murder of Stephen Lawrence which found the Metropolitan Police Force o to be guilty of Institutionalised Racism and in so doing provided a more specific definition of the term as -:

The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin which can be seen or detected in processes; attitudes and behaviour which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantages minority ethnic people." However it should be noted that accusations of institutional racism within the UK police force continue to this day.

Professor Lander notes further that “Institutional and structural racism work hand in glove. Institutional racism relates to, for example, the institutions of education, criminal justice, and health. Examples of institutional racism can include: actions (or inaction) within organisations such as the Home Office and the Windrush Scandal; a school’s hair policy; institutional processes such as stop and search, which discriminate against certain groups. Structural racism refers to wider political and social disadvantages within society, such as higher rates of poverty for Black and Pakistani groups or high rates of death from COVID-19 among people of colour.”

In his recent book “Racism: a very short introduction” Professor Ali Rattansi suggests that another useful distinction may be made between institutional racism and institutional racialisation so that rather than attempting to determine whether particular institutions are or are not institutionally racist we should consider the extent to which institutions are institutionally racialised.

Racism Within Schools: Individual or Institutional

It is difficult to assess the true extent to which teachers hold racist views and, if they do, the extent to which such views are carried over into classroom practice. However the effects of schools themselves on the educational achievements of ethnic minority members has been researched in several relatively small scale studies which [although they may not be entirely representative] do point to the existence of some conscious and considerable unconscious racism but suggest also that it is difficult to generalise about students' actual responses to negative labelling .

One of the first people to focus on the role of the British education system in the generation of West Indian underachievement was Bernard Coard. In his study How the West Indian child is made educationally subnormal in the British school system: the scandal of the Black child in schools in Britain [1971] he argued that the British education system made Black children feel inferior in several ways several of which pointed to the existence of Institutional Racism:

- They are told that their accent and language are inferior.

- White is associated with good and black with bad.

- White culture is celebrated while Black culture is ignored.

- Pupil racism is widespread.

- Black pupils are adversely affected by labelling, streaming and self-fulfilling prophecies.

Bernard Coard succeeded in articulating very powerfully the concerns of the Black community and other writers have provided strong support for his general conclusions in their much more detailed studies by, for example, E. Brittan, Cecile Wright and Heidi Mirza. D. Gillborn and D Youdell. The continuing importance the work of Bernard Coard has recently been illustrated by the re-publication, updating and further discussion of his work in Tell It Like It Is: How our schools fail Black children {edited by Brian Richardson 2005] .

Click here and here before two Guardian articles by Bernard Coard which were written published to coincide with the republication of his book

Then the situation described by Bernard Coard has been movingly portrayed in episode one of the Axe series of dramas screened by the BBC. You may click here to watch the drama which is part of the Small Axe series and click here and here for two Guardian articles about it. Also click here for a Guardian article about a group of people subjected to this discrimination in the 60s and 70s who are now campaigning for compensation.

You may Click here for two students discussing the current relevance of Bernard Coard’s work.

Finally, you may click here to see that Bernard Coard has subsequently had an eventful life.

In Cecile Wright's research in primary schools [1992] it is suggested that teachers often failed to involve Asian pupils sufficiently in class discussion because of an inaccurate assumption that these students had poor language skills and that they also undervalued Asian culture in some respects. However, teachers also had higher expectations of Asian origin than of Afro-Caribbean origin pupils.

Heidi Mirza's 1992 study of black and white secondary school pupils aged 15-19 suggested that although there was evidence of teacher racism and negative labelling this did not undermine the self-esteem of the pupils. There were also many white teachers who genuinely wanted to help their black students, but this help was sometimes misguided and the students actually received more effective help from black teachers. In some cases although the pupils were keen to do well, Mirza believed that they were held back because of poor relationships even with well-meaning white teachers

Heidi Mirza: Young, Female and Black [1992] Some additional detail

Heidi Mirza's study is located in two South London Comprehensive schools: one a coeducational Catholic School and the other a single sex Church of England school It focuses especially on 62 black girls aged 13-19 and as will be seen the religious dimensions of these schools had important implications for the conclusions of the study. Among the key conclusions are the following.

- There was no evidence that the young black women ion the study had negative self-images as a result of being black. So much for doll studies!

- There was also no evidence that the activities of teachers undermined the self -esteem of the black students.

- However it was highly likely that the activities of the teachers did undermine the black students' educational prospects in various ways as will be indicated below

- Heidi Mirza argues that the teachers in the study could reasonably be classified into 5 groups: "the overt racists [33%" "the Christians" [ note the religious character of the school];" the crusaders[2%]"; "the liberal chauvinists[25%]]" and the black teachers [4 teachers in total]. By implication about 40% of the teachers were Christians or unclassifiable.

- Heidi Mirza gives several examples of grossly racist attitudes and behaviour among teachers in the study. In the words of one History teacher "African history is so boring...the discussion of slavery is monotonous in school teaching...it has no bearing on anything."

- The "Christians" are presented as an essentially well -meaning group who believed that broadly speaking the schools treated all pupils equally irrespective of their ethnicity so that the specifically anti-racist policies supported by the then ILEA were actually likely to promote ethnic tensions where none previously existed. Heidi Mirza suggests that this meant that the real incidence of racism within the schools remained unaddressed with negative consequences for the prospects of ethnic minority pupils.

- The "liberal chauvinists" are presented as believing that they had the best interests of the black pupils at heart but as in reality making inaccurate assumptions about the attitudes and values of the black community. In particular these teachers often argued that black pupils, encouraged by their parents, actually had unrealistic, over-ambitious expectations which it was the teachers' duty to curtail in order to prevent subsequent disappointment. Clearly this apparently well-meaning approach was likely to undermine ambitions which were both high and realistic.

- There were a small number of "crusaders" who believed that school practices were infused with racism and that the anti-racist policies of the then ILEA should be strongly supported. These teachers were generally unpopular with the other teachers and unfortunately their anti-racist teaching initiatives were often seen by the black pupils as unrealistic and impractical.

Finally, there were a small number of black teachers who did not support radical initiatives but aimed to help black pupils as much as they could in practical ways within the existing school environments. The black pupils felt that these black teachers were supportive but not positively biased toward black rather than white pupils. Heidi Mirza concludes "On the whole the black teachers were more in tune with the needs of their black female pupils offering a more positive solution to the education of the black child.".

Mac An Ghaill [1992] investigated the experiences of Afro-Caribbean and Asian origin students in Further Education. All the students were conscious of racism in UK society generally but disagreed about the extent of racism in the education system. Students did not necessarily allow racism and negative labelling to affect them adversely. Instead, they adopted various survival strategies to improve their prospects: "survival through accommodation, making friendships with helpful teachers and keeping out of trouble."

Institutional Racism: Some Further Discussion

Click here for Race and Racism in English Secondary Schools: Dr Reni- Joseph Salisbury for The Runnymede Trust 2020

It has been argued Institutional Racism may be said to exist in some individual schools and within the UK education system as a whole as a result of the following characteristics,

- Rules designed to promote equality of opportunity may not be fully applied.

- School selection policies which have been introduced as a result of the quasi-marketisation of education may restrict the entry of some ethnic minority pupils to well subscribed effective schools and increase their segregation in less successful schools.

- Setting and banding systems may operate to the disadvantage of some ethnic minority pupils.

- School curricula may not fully reflect the cultures and interests of ethnic minority pupils.

- Afro- Caribbean pupils are especially likely to be excluded from school either temporarily or permanently.

- Ethnic minority members are under-represented within the teaching profession and especially at the higher levels of the profession.

- Increasing concerns have been raised that the adultification of some ethnic minority pupils has created special problems for them.

- The Issue of Police in Schools

Let us now consider these possible categories of Institutional Racism in Education in more detail.

- Rules designed to promote equality of opportunity may not be fully applied.

Click here for Race and Racism in English Secondary Schools: Dr Reni- Joseph Salisbury for The Runnymede Trust 2020 pp17-20

The Runnymede Trust notes the following issues.

- There is evidence of considerable interpersonal racism within schools which may involve both verbal and physical abuse, but it is argued that in many schools policies for dealing with this are inadequate.

- In many cases although schools have frameworks for dealing with racist incidents, responsibility in practice often devolves to individual teachers who may have insufficient training for the task. Click here for an article on the inconsistencies of school policies.

- Policies which appear to be “race neutral” may in fact discriminate against black pupils as in the case of school hair policies which may rely upon discriminatory value judgements of what is and what is not “neat and tidy”. Click here for a Guardian article on schools’ discriminatory hair policies

- There are concerns that current Prevent policies operating in schools may discriminate against Muslim pupils.

- There concerns that in some cases the recent attention given to the relatively low attainment levels of white working class pupils has resulted in the introduction of school policies which have distracted attention from the educational difficulties experienced by some ethnic minority pupils.

Click here for an article on the Myth of a post-racial society by Prof. Kalwant Bhopal and Click here for information about her book White Privilege : the myth of a post-racial society

For several items from the Guardian on racism with schools Click here and here and here and here and here.

Click here and here for proposed reforms

- The Quasi- Marketisation of State Education

It has also been argued the State policies involving the quasi-marketisation of education introduced by Conservative governments [1979-97] and extended by Labour and Coalition and Conservative Governments thereafter have actually benefited middle parents and their children disproportionately since it is these middle class parents who are much more likely to be able to use their cultural, economic and social capital to secure entry to oversubscribed effective state schools thereby indirectly reducing the educational opportunities of more disadvantaged pupils. Insofar as ethnic minority families are disproportionately likely to be working class and to experience varying degrees of racial prejudice they may find it especially difficult to secure entry for their children to effective schools although it is also the case that schools may be especially keen to attract Chinese pupils from all social classes since even Chinese pupils eligible for free school meals are highly likely to gain good examination results while Indian students also are more successful than white British students . Bangladeshi students in recent years have overtaken White British students in GCSE attainment and the attainment gap between White British students and Pakistani students has narrowed appreciably in recent years The attainment gap between White British and Black Caribbean students has also narrowed but remains more substantial.

These issues are described in detail in a study by S. Gerwirtz, S. Ball and R. Bowe entitled Markets, Choice and Equity in Education [1995] and you should consult your textbooks to familiarise yourselves with the details of this very useful study which is relevant to several aspects of the Sociology of Education.

- Setting and Banding

In a significant study of two London Comprehensive schools, Gillborn and Youdell [2000] argued that ethnic minority students were disadvantaged in several respects. There were few cases of open teacher racism and many teachers were committed to helping ethnic minority students but the authors argued that the relative failure of Afro-Caribbean students could be explained by the facts that when all students were tested on entry to the schools , black students were more likely to be consigned to lower sets and to remain there for the rest of their school careers, especially because if they had remained in lower sets in Years 8 and9 they would not have worked in sufficient depth for them to access the higher level worked covered in the top sets in years 10 and 11. Consequently among other things this meant that they were most likely to be entered for lower tier GCSE examinations. Then, due to a system of educational triage, teachers concentrated their attention firstly on borderline cases who might gain 5 A*-C GCSEs, secondly on high achievers and only minimally on students [who were often black] who were considered unlikely to gain A*-C passes. Negative teacher expectations therefore had affected the achievement of Black students.

However in Uncertain Masculinities: Youth, Ethnicity and Class[2000] Sue Sharpe and Mike O'Donnell argued on the basis of a study of 4 London Secondary schools that earlier studies pointing to the existence and adverse consequences of negative labelling may now be rather outdated as head teachers and classroom teachers have increasingly devised and implemented schools equal opportunities policies which have reduced significantly the likelihood of discrimination against pupils. Yet in April 2005 several educationalists writing in The Guardian submitted "Letters to the PM" assessing the effectiveness or otherwise of Labour's Education Policies between 1997-2005. In his contribution Professor David Gillborn focussed on Ethnicity and Education and suggested that most of the criticisms made over the last 30 years of the UK education system's approach to the education of ethnic minority groups were still valid , that the increased use of setting in recent years was if anything making matters worse for many ethnic minority pupils and that many schools were still failing to implement equal opportunities policies effectively. Click here for Professor David Gillborn's 2005 letter to the Guardian.

More recent research by Professor Steve Strand supports this conclusion. Professor Strand's article is entitled The White British-Black Caribbean Achievement Gap: Tests, Tiers and Teacher Expectations and was published in the British Educational Research Journal [ Feb 2012] Here is a brief summary of the conclusions taken from the BERJ website.

A recent analysis of the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LSYPE) indicates a White British–Black Caribbean achievement gap at age 14 which cannot be accounted for by socio-economic variables or a wide range of contextual factors. This article uses the LSYPE to analyse patterns of entry to the different tiers of national mathematics and science tests at age 14. Each tier gives access to a limited range of outcomes with the highest test outcomes achievable only if students are entered by their teachers to the higher tiers. The results indicate that Black Caribbean students are systematically under-represented in entry to the higher tiers relative to their White British peers. This gap persists after controls for prior attainment, socio-economic variables and a wide range of pupil, family, school and neighbourhood factors. Differential entry to test tiers provides a window on teacher expectation effects which may contribute to the achievement gap.

You may click here for a similarly critical assessment of tiering by Jo-Anne Baird published in the Conversation in 2014.

Criticism of tiered GCSE examinations has continues as is indicated in this 2022 article based on a study of Welsh and Northern Irish pupils which indicates the allocation of pupils to tiers may be affected by teachers’ unconscious biases which may result in discrimination against girls and against Black Caribbean pupils as is shown in the following extracts .

“The use of tiering has reduced over the last decade because of concerns about equity issues. Grade restrictions on foundation and intermediate tiers mean that students’ attainments are capped, with repercussions for their future trajectories.[1] Tiering also leads to inequalities in the curriculum – the foundation tier offers a restricted curriculum which limits students’ learning.[2] The other issue is how decisions are made about which students should be entered into which tier. This is a difficult task, and one which can be impacted by unconscious bias. Previous research conducted in England indicated that girls were disproportionately entered into the intermediate tier for mathematics because teachers’ perceived girls to be more anxious about their performance than boys and would struggle with the pressure of the higher paper.[3] Similar trends have been identified in relation to ethnicity, with Black Caribbean students less likely to be entered into higher tiers, even when prior attainment and other factors are accounted for.[4]”