Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Part Three Neo-Marxism and Neo-Weberianism

- Neo-Marxism andthe Rejection of Post-Capitalist Theories

Modern Marxists have rejected all of the above-mentioned post-capitalist arguments and argued that a modernised form of Marxist theory still offers the best theoretical framework for the analysis of contemporary capitalist societies. Important Neo-Marxist contributions to the analysis of modern capitalism include the following.

- The work of Antonio Gramsci, who argued for a less economically determinist reading of Marx, emphasising the importance of capitalist hegemony and of long term strategies for the transition to Socialism and subsequently to Communism. Click here for further information on Gramsci.

- The work of Ralph Miliband in The State in Capitalist Society (1969) and in later studies such as Divided Societies (1991).

- The Miliband-Poulantzas debate over the nature of the capitalist state.

- The work of Erik Olin Wright on contemporary capitalist class structures (see below).

Also very significant is the work of John Scott Who Rules Britain? (1991], who combines Marxist and Weberian insights to argue that in the UK a very small capitalist class comprising perhaps 0.1% of the population (about 450,000 people) exists, and that this small capitalist class is also effectively a ruling class (see below).

Also Click here for a very useful article by Graham Scambler entitled From Power Elite to Ruling Oligarchy which focuses on the economic and political power of the super rich

As well as providing useful information on the nature of capitalist class structures and the nature of capitalist states, some of these studies also call into question whether radical socialist change in advanced capitalist societies is to be achieved via revolutionary change, on the Russian model, and whether capitalist working classes can any longer be regarded as potentially revolutionary classes, as in orthodox Marxist theories.

Please note that I cannot do justice to the complexity of these contributions in this short summary, but I hope that the introductory points which I do make will encourage students to investigate some of this work for themselves if they are pursuing their Sociology studies beyond their Advanced Level Sociology courses.

5.1 Ralph Miliband, The State in Capitalist Society

One of the best-known reassertions of the continued relevance of Marxist theory was provided by Ralph Miliband in his study The State in Capitalist Society [1969]. In this study, Miliband aims to disprove the claims of the post-capitalist theorists which have been outlined above and to show that an economically dominant class continues to exist in capitalist societies, and that this class exercises decisive influence over the activities of capitalist states. (Click here for an article on Ralph Miliband's The State in Capitalist Society.)

Miliband makes the following arguments, most of which would be accepted by most contemporary Marxists.

- The conclusions of the Managerial Revolution were inaccurate, because even if large companies were increasingly controlled by their senior managers rather than their owners, there would be no significant change in business practices because of the similarities of class background and (by implication) of attitudes and values of managers and owners, because managers often own large amounts of shares, and because other company survival and growth depends ultimately on high profitability.

- Nationalisation had not reduced the power of the capitalist class because generous compensation had been given, because the profitable sector of private industry had not been nationalised, and because nationalised industries recruited managers from private industry who followed broadly similar business objectives. Nationalised industries might even indirectly subsidise private profit from time to time by charging lower prices than might have been the case if these nationalised industries had remained in the private sector.

- Changes in the UK capitalist class structure had been far less significant than suggested by post-capitalist theorists:

◦ It was claimed by Marxists and others that any redistribution of income and wealth which had occurred during the first half of the 20th century was mainly between the rich and the comfortably off (and often members of the same families), with little improvement in the relative position of the poor.

◦ Even if the skilled sections of the working class had become more affluent, they remained significantly worse off than most members of the middle class and had not by the mid-1960s significantly changed their attitudes and values, and continued to vote primarily for the Labour Party in general elections.

◦ Abel-Smith and Townsend had demonstrated that poverty, at least in a relative sense, had not been eliminated by the Welfare State which, in any case, according to Marxists and others, operated as an important agency of social control.

◦ Social class differences in educational achievement remained significant, and the chances that working-class people might be upwardly socially mobile into the upper class were far smaller than the chances that people born into the upper class would remain there; members of the dominant economic class could relatively easily pass on wealth, power and privilege to their children, therefore facilitating the social reproduction of the capitalist class structure from generation to generation.

Thus, MiIiband concluded, a dominant economic class continued to exist and to exercise economic power in the private sector. He went on to argue that this dominant economic class was also a politically dominant ruling class which exercised decisive power over the State such that the capitalist state served the interests of the dominant class, usually at the expense of the rest of the population. Miliband argued that the theory of democratic pluralism provided a grossly inaccurate explanation of the distribution of political power, although, at the same time, he did not argue that the power of capital is the only factor determining the direction of State activity, but rather that it is by far the dominant factor and that working class organisations (the Labour Party and the Trade Unions) are engaged in "imperfect competition" with it .They may in certain circumstances gain important victories for the working class, but these victories do not challenge the overall dominance of capital and may in fact, ultimately, help to sustain it by sustaining what Marxists consider to be the myth of pluralist democracy.

5.2. The Miliband-Poulantzas debate

Miliband's analysis as outlined in The State in Capitalist Society has been criticised from a Structuralist Marxist perspective by Nicos Poulantzas. The main elements of Poulantzas' approach may be outlined as follows:

- Poulantzas adopts a broad definition of the State to include the Family and the Education System. Here, his approach is similar to that of Althusser in his use of ideological state apparatuses.

- Poulantzas argues that individuals’ actions are determined less by their own attitudes and values and more by the positions which they occupy within the structure of society. For example, a senior Civil Servant helping to devise economic strategies in a liberal democracy will be obliged to take certain decisions irrespective of his/her own personal views or social background because the capitalist state depends upon the existence of a thriving capitalism economy to generate employment and taxation revenues without which the capitalist state cannot function. Similarly, the environmental policies to be pursued by capitalist states are constrained by perceived needs to maintain the profitability of capitalism. This implies, to Poulantzas, that Miliband, in The State in Capitalist Society, has overestimated the importance of shared social background of state and business elites and has underestimated the force of the structural constraints of capitalism, which helps to explain the failure of social democracy to transform capitalism despite the working-class origins of some of the leaders of social democratic governments.

- The Bourgeoisie is not a unified class but consists of different fractions (big business, small business, manufacturing capital, finance capital, importers, exporters, high tech, low tech etc.) which may experience important conflicts of interest over the detailed organisation of capitalism even though they have a common interest in the continuation of the system as a whole. The relative power of the different fractions of the capitalist class varies over time, but in the UK context, Marxists have tended to argue that it is finance capital which has been able to exert decisive influence over state policy, sometimes at the expense of other fractions of the capitalist class.

- According to Poulantzas, the institutions of the State operate with some Relative Autonomy. This is the most significant phrase in the Poulantzas theory. Because of the differences of opinion within the capitalist class, and because it will sometimes be necessary to make concessions to the working class, the State needs to have some freedom of manouevre to resolve disputes and make concessions so as to ensure the continuation of the capitalist system as a whole. However, the freedom of the State is itself limited by the fact that it, too, operates within the constraints of a capitalist system.

Thus, according to Poulantzas, the State is a little more independent of the Bourgeoisie [i.e. relatively autonomous] than it is according to the early work of Miliband, although following some theoretical disputes in the I970s, Miliband did move a little closer to the Poulantzas position while warning of the dangers of what he called structural super-determinism!

5.3 Ralph Miliband, Divided Societies

Although The State in Capitalist Society (1969) is probably Ralph Miliband's best known work, I also recommend strongly Divided Societies (1991). In this study, Ralph Miliband developed a model of a fragmented capitalist class structure, which to some extent reflected some of the ideas which had been developed by C.W. Mills in his study The Power Elite. Thus, in Miliband's new model, capitalist class structures could be divided into 8 sections.

A dominant class containing four sections:

- a dominant Economic Elite: the people who wield corporate power by virtue of their control of major industrial, commercial and financial firms.

- a dominant Political Elite: Presidents, Prime Ministers Cabinet Ministers, Senior Civil Servants, Judges.

These two sections, the dominant economic elite and the dominant political elite, together make up the Power Elite.

The next two sections are those parts of the dominant class that do not belong to the power elite:

- the people who control and may also own a large number of medium-sized firms.

- members of a large professional class of lawyers, accountants, middle-rank civil servants, military personnel, senior university teachers – in short "people who occupy the upper levels of the credentialised part of the population".

5 and 6. These two sections comprise the "Petty Bourgeoisie or lower middle class". It should be noted here that many other theorists use the term "Petty Bourgeoisie" to refer to owners of small businesses and self-employed craftsmen (they are usually men). However, in Miliband's formulation the Petty Bourgeoisie encompasses owners of small businesses and self-employed craftsmen plus "semi-professional, sub-managerial, supervisory" workers such as teachers, social workers, lab technicians and lower-level civil servants and local government officials". This seems to be a slightly unorthodox usage of the term “Petty Bourgeoisie”.

- the working class, which obviously includes skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers. However, according to Miliband it also includes "clerical, distributive and service" workers, as well as the wives or partners of these workers who may not themselves be in employment. It also includes unemployed persons, pensioners and the children of working-class parents. On this basis Miliband argues that the working class accounts for about two-thirds to three-quarters of the population. However, others would argue that this overstates the size of the working class and that, for example, many routine non-manual workers might more accurately be regarded as members of the lower middle class. [See section below on the Proletarianisation of the Clerical Worker]

- the underclass, which is recruited from the working class and made up of the poorest and most deprived sections of the working class and is therefore distinct from the bulk of wage earners. These workers are the long-term unemployed, the disabled and the long-term sick who are heavily dependent upon state benefits and/or help from relatives and/or charity. It must be noted that Ralph Miliband does not subscribe in any way to the neo-liberal version of the underclass associated with theorists such as Charles Murray. These theories of the underclass and criticisms of them are discussed briefly below and will be discussed in more detail in a new document.

Thus Miliband offers a Neo-Marxist model of capitalist class structure which emphasises the continued dominance of economic and political elites while recognising the fragmentary nature of the class structure. He also reiterates his arguments form The State in Capitalist Society stating that theories of post-capitalism are inaccurate in several respects, and that capitalist states continue to be dominated to a considerable extent by interlocking economic and political elites.

As already mentioned, Marx and Engels stated in the Communist Manifesto that "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles", and Miliband devotes two chapters in his study to the politics of class struggle. He argues that since the C19th workers have been able to exert at least some pressure from below to secure voting rights, trade union rights and the development of the Welfare State which have at least improved workers' living standards to some extent. However, he accepts also that the working class could not at any stage of its history be regarded as a revolutionary class, and that in the case of the UK, the trades unions and the Labour Party have been far more concerned to promote gradual social reform of the capitalist system rather than its transformation.

Meanwhile, he argues that the dominant economic class and the state which primarily reflects its interests have been involved in class struggle from above to secure the maintenance of the capitalist system. For example, in the era of the post-war consensus, trade unions have been incorporated into economic decision-making processes as a means of curtailing their radicalism. Furthermore, in the era of Thatcherism, new industrial relations legislation has been used to reduce trade union power; income inequality, which had been reduced during the post-war consensus, increased significantly in the Thatcher era due to the introduction of more regressive taxation and the abolition of wages councils designed to protect the incomes of the lower paid; and despite some expansion of welfare state spending, high levels of relative poverty remain, as do inequalities of educational opportunity and social class differences in health and in life expectancy. These patterns of inequality persist to a considerable extent because the capitalist-controlled mass media orchestrate propaganda in support of the capitalist system and against leftist critics of capitalism, and other agencies of socialisation such as the family and the education system tend to encourage conformity with the capitalist status quo.

Whereas it is argued in classical Marxism that the working class would be the ultimate agent of revolutionary change, Miliband agreed that up to the late 1980s there had been very little evidence of revolutionary working-class consciousness, and that trade unions and social democratic / socialist parties had failed to address adequately the existence of significant inequalities based on age, gender, race and sexuality or the increasing likelihood of environmental damage. It consequently came to be argued that these issues could be better addressed by new social movements of various kinds that were prepared to focus their attention more specifically on these particular issues, rather than via class-based politics.

However, Miliband argues that these problems derive essentially from the existence of capitalism as a system in that it is working-class women, working-class ethnic minority members, and working-class gay people who are most likely to experience most strongly the effects of discrimination, and that it is the capitalist system which is the ultimate cause of environmental damage. He therefore believes that political unity among new social movements, socialist/social democratic parties and trade unions is essential if these issues are to be addressed effectively, and that greater efforts must be made to encourage working-class people to recognise the evils of ageism, sexism, racism, homophobia and environmental damage if progress is to be made. Thus, although class politics remains central to Miliband's strategy, he recognises the need for a coalition of progressive forces if radical [and anti-capitalist] change is to be achieved.

Click here for information on Socialism for a Sceptical Age, Ralph Miliband's final book, published in 1994.

5.4. Neo-Marxism and Capitalist Class Structures: Erik Olin Wright

Marxist theories have sometimes been criticised on the grounds that his theory of class polarisation predicted the relative decline of the middle class, whereas in practice from the mid-19th century onwards it is very clear that, for a variety of reasons, non-manual employment has increased relatively to manual employment in capitalist societies, suggesting that the relative size of the middle class has actually increased rather than decreased. However, as mentioned at the beginning of this document, Marx did in his later work predict the growth of the middle class, and modern Marxists have also suggested that one should not equate the growth of non-manual employment with the growth of the middle class because routine non-manual clerical work has to a considerable extent been proletarianised such that many clerical workers can more accurately be described as members of the working class rather than as members of the middle class, although many non-Marxist sociologists have rejected the theory of the proletarianisation of the clerical worker.

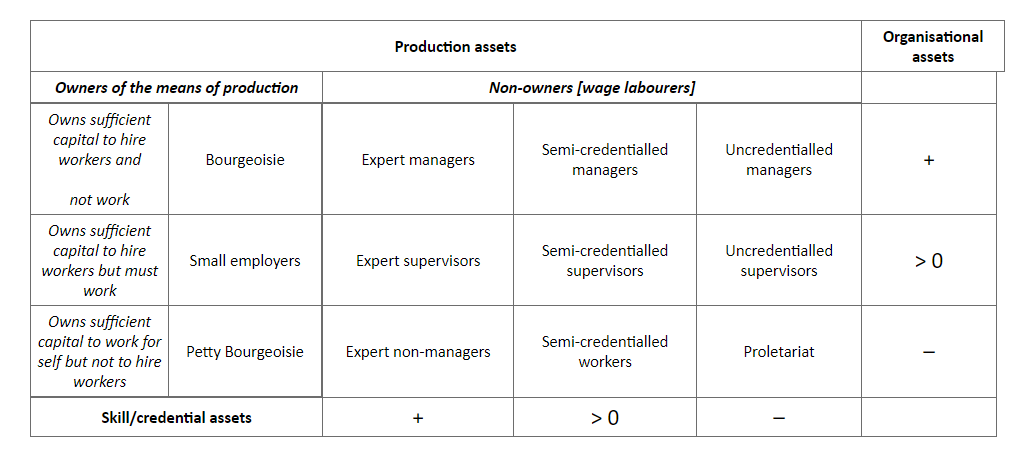

Neo-Marxist theories which recognised the growth of the intermediate strata and the increased fragmentation of contemporary capitalist class structures were developed by Erik Olin Wright. In Wright’s first theory, he distinguishes between the capitalist mode of production and “simple commodity production”, and between social classes and contradictory class locations. Thus, the Bourgeoisie are a social class because they both own the means of production and exercise strategic control over the production process. The Proletariat are also a social class because they are non-owners of the means of production and have zero or negligible control over the production process. The Petty Bourgeoisie are small-scale owners of the means of production but do not hire labour. They are seen as a capitalist class but operating outside of the capitalist mode of production.

Other social groups are in contradictory class locations: managers and supervisors do not own the means of production but do exercise some control over other workers and over the production process; small employers own and control their means of production but employ very few workers; and semi-autonomous workers do not own the means of production but do have some control over their own labour. E.O Wright's first theory is illustrated in the diagram below.

In E.O Wright’s second model, class membership depends upon ownership or non-ownership of the means of production, credentials (i.e. qualifications), and degree of control in the work place. This leads to a 12-class model of the class structure with 3 ownership classes and 9 non-owner classes. The non-owner classes vary in terms of their possession of skill/credentialled assets and organisational assets. Thus, in the model there are several intermediate groups, although there is no single middle class, while the Proletariat has neither skill/credentialled assets nor organisational assets. There are clearly some similarities with a Weberian approach, given the high degree of fragmentation; Wright also admits that the working class may not be a revolutionary class. As a result, some sociologists have concluded therefore that his work is barely recognisable as Marxist, while Wright himself came to describe his theoretical approach as one of "pragmatic realism" in which he was prepared to combine differing approaches to class analysis.

[If you require more detailed information on Erik Olin Wright, Click here and here and here for Prof. Graham Scambler's blog posts on Erik Olin Wright.]

[If you are intending to pursue your studies of social stratification in more detail, I strongly recommend that you read the work of Erik Olin Wright himself. Click here for the website of Erik Olin Wright and here for a recent article by Erik Olin Wright. Vi these links you will find some of Erik Olin Wright's detailed contributions to the development of Neo-Marxist scholarship. Erik Olin Wright passed away in January 2019 [R.I.P.].

[Advanced Level Sociology students approaching the study of Marxism for the first time should begin with more introductory explanations of Marxist theories before consideration of Professor Wright's work, which is, however, mentioned explicitly in the Stratification and Differentiation option within the AQA syllabus, although for examination purposes students should concentrate on Professor Wright's models of the capitalist class structure which are discussed above.]

5.5. John Scott, Who Rules Britain? [1991]

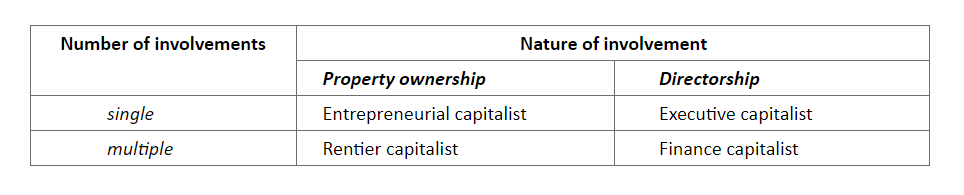

Modern Marxists have agreed that in the UK, as in other advanced capitalist societies, a dominant economic class continues to exist, deriving its income mainly from its investments and/or very large salaries. However, there are disputes as to the size and characteristics of this dominant economic class. For example, writers such as J. Westergaard and H. Ressler (Class in a Capitalist Society 1976) argue that this class represents perhaps 5%–10% of the UK population, whereas John Scott combines Marxist and Weberian insights to argue that in the UK a very small capitalist class comprising perhaps 0.1% of the population (about 450,000 people) exists, and that this small capitalist class is also effectively a ruling class. Scott’s analysis of this capitalist class uses the following analytical framework.

Entrepreneurial capitalists approximate to the Marxian Bourgeoisie. They are individuals who either own their companies outright or are majority shareholders, and they involve themselves very directly in the organisation and management of their companies.

Rentier capitalists are wealthy individuals who own large amounts of shares in more than one company. They do not take an active role in the organisation and management of these companies, but they take a keen interest in share price trends, and given their large financial holdings may well have a substantial influence on company policy.

Executive capitalists are directors and senior managers of large companies. They receive very high salaries and may also have substantial shareholdings in the companies which they control and manage, although their personal shareholdings will represent only a small proportion of the total shareholdings in those companies.

Finance capitalists are directors and senior executives of financial institutions such as unit trust companies, pension funds and banks which own significant proportions of company shares. They are appointed to boards of directors of companies in which their institutions have significant shareholdings and may well sit on the boards of more than one company.

John Scott also points out that the categories in the above table should be regarded as "ideal types" in the Weberian sense. In reality, individuals may simultaneously occupy more than one position within the above quadrants, and they may also move between the different categories. Thus, it is possible that an entrepreneurial capitalist will own significant amounts of shares in other companies, and that significant rentier capitalists may be co-opted onto the boards of companies in which they have significant shareholdings.

The role of finance capitalists in the determination of company policies has become increasingly important as an increasing proportion of company shares has come to be owned by financial institutions. Here John Scott presents data for the 1980s, but the trend is apparent also in the most recent data. Click here for recent data on institutional share ownership.

He then discusses long-term trends in the distribution of income and wealth, noting that from the 1940s to the mid-1970s there were trends toward greater income equality and, to a lesser extent, to greater wealth equality. but that these trends were reversed during the 1980s. He then argues that although the richest 1% of the population might be seen as especially affluent, "this is a much wider group than the capitalist class which is a considerably smaller group than the top 1%", and that "the core of the capitalist business class comprises about 0.1% of the adult population". He then presents data on the wealth of the most wealthy families within the core of the capitalist class in 1990, recognising that these can be regarded only as estimates since full data on wealth ownership are simply unavailable.

More recent data which were cited at the beginning of this document indicate that the increases in income inequality which occurred in the 1908s and 1990s have not been reversed in the last 20 years, and that wealth inequality remains very considerable. For example, Click here for a Parliament Research Briefing on Income Inequality in the UK, Click here for Rich List 2019 [BBC], and here for Rich List 2020 [BBC], which provides recent information on Britain's richest individuals and families.

In the final chapter of his book, John Scott argues that "Britain is ruled by a capitalist class whose economic dominance is sustained by the operation of the state and whose members are disproportionately represented in the power elite which rules the state apparatus. That is to say Britain does have a ruling class." Thus, although throughout his study John Scott does point to important differences between his analysis and that of Ralph Miliband, both authors do point to the very high levels of political influence of the dominant economic groups within UK society.

Thus Neo-Marxists have criticised theories of post-capitalism and updated Marx' theories of the class, state and revolution. They recognise that capitalist class structures have become more complex and fragmentary but continue to argue that ownership and non-ownership of the means of production remain important determinants of class membership and that, since capitalism is characterised by the private ownership of the means of production, classes are inevitable under capitalism. It is inevitable also that the economically dominant capitalist class [however defined] will also exercise considerable dominance over the activities of the state. In the context of modern capitalism, Marx's theories of working-class revolution require significant modification.

- Neo-Weberian Theories and ClassInequality

It has been argued that Marx's theory of social classes is inadequate in that he is said to have concentrated too much on the Proletariat and the Bourgeoisie and failed to predict the growth of the middle class, although, as already mentioned, he did predict this in his later theories.

Critics also argued that Marx underestimated the importance of non-class differences in societies. Gender and ethnic differences may be given inadequate coverage in Marxist theory.

It is also claimed that Marx underestimated the importance of divisions within the main social classes – for example, the importance of the divisions between skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled working-class people that might reduce their class solidarity and, therefore, reduce the likelihood of revolution.

The German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) made several important criticisms of Marx's class theories:

- A person's class position depended not only on ownership or non-ownership of wealth but also on their incomes, fringe benefits and opportunities for social mobility. These variables, combined together, described an individual'sMarket Situation.

- Capitalist societies could be divided into 4 main social classes: the propertied upper class, the property-less white-collar workers, the Petty Bourgeoisie, and the manual working class.

- Divisions within classes might occur as a result of divisions of status within these classes. While class, as we have seen, is basically an economic concept, status refers to one's standing or prestige in society. It might be the case, sadly, that black people have less status than white people in the UK, or that Catholics have less status than Protestants in N. Ireland, and these status differences may restrict the unity of the working class.

- Divisions within these social classes were more important than Marx thought. Such divisions might mean that the working class would never unite and that, as a result, anti-capitalist revolutions simply would not occur.

- In any case, even if apparent socialist revolutions did occur, they would serve only to entrench the powers of party and state bureaucracies rather than leading to the emancipation of the working class.

From the 1950s onwards, Weberian sociologists have made very important contributions to the analysis of UK capitalism.

In Neo-Weberian analyses of the UK class structure, it is argued that although the UK class structure is fragmentary, it would certainly be incorrect to argue that the UK is becoming an increasingly classless society. Examples of the Neo-Weberian approach include the following (each of which are discussed in more detail in my documents on Weberian Theories of Stratification will be available shortly).

- The Proletarianisation Theory: The Black Coated Worker and its aftermath

- The Embourgeoisement Theory: The Affluent Worker studies and their aftermath

- The Oxford Social Mobility Study and the subsequent development of the NS SEC class schema.

6.1. The Proletarianisation Theory: The Black Coated Worker and its aftermath

In The Black Coated Worker (1958), David Lockwood aimed to analyse the class position of clerical workers and to assess whether they were experiencing a process of Proletarianisation. In this study, Lockwood adopted a recognisably Weberian approach and measured the class position of clerical workers in terms of their market situation, their work situation and their status situation. His conclusion was that the class position of clerical workers was uncertain for the following reasons:

- In terms of their market situation, clerical workers, even in the 1950s, were earning less than many skilled manual workers

although they did continue to enjoy fringe benefits such as better working conditions plus sickness and pension schemes not available to manual workers.

- With regard to their work situation, at least in relatively small-scale offices, clerical workers enjoyed closer working relationships with senior management than did manual workers, although this was changing in large open-plan offices and typing pools.

- Clerical workers continued to enjoy a higher status in the community than did manual workers, although this, too, was changing.

Insofar as the class position of clerical workers was gradually deteriorating, this could be explained by the facts that the expansion of education meant that many more people now had the skills necessary to undertake clerical work, and that trades unions had succeeded in gaining substantial pay increases for manual workers which meant that clerical workers no longer enjoyed an earnings advantage in many cases. As a result of this, clerical workers, too, increasingly joined trades unions. To repeat, Lockwood saw that the class position of clerical workers was changing, but he argued that by the late 1950s they occupied a position somewhere between the working class and the middle class.

There have been several more recent studies of the class position of the clerical worker, some of which accept the Proletarianisation Theory and some of which reject it. For example, John Goldthorpe has argued that clerical workers should not be described as working class because many of them are young and can reasonably expect to move on to managerial positions in later life, so they are unlikely to adopt a working-class identity during their relatively short time as clerical workers. Conversely, Rosemary Crompton and Gareth Jones have claimed that clerical work is increasingly done by women, and that their chances of promotion to managerial level are much smaller, such that they can be described as part of the proletariat or working class.

Several complex issues are involved in the detailed analysis of the Proletarianisation Theory, but in view of the disagreements that exist between real experts in this area, it surely does seem reasonable to conclude that the class position of clerical workers is uncertain.

6.2. The Embourgeoisement Theory: The Affluent Worker studies and the fragmentation of the working class

In the 1950s and 1960s, so called post-capitalist theorists were claiming that capitalist societies were evolving into post-capitalist societies characterised by a shift in the occupational structure from unskilled to skilled manual and non-manual work, full employment and a more equal distribution of wealth and income and increased provision of welfare services by the State which implied, for example more equality of educational opportunity and the reduction of poverty at least in an absolute sense. Also, nationalisation of several basic industries meant that they were now supposed to operate more in the interests of the consumer and the rise of the Labour Party, and the growing strength of the trade unions implied that working class people could share more fully in the use of political power which had previously been monopolised indirectly by the upper class. Thus, it came to be argued that Marxist theories of the state were now deemed increasingly irrelevant as political power could be analysed much more accurately via theories of Democratic Pluralism [although neo-Marxists such as Ralph Miliband were quick to argue that it was the theories of democratic pluralism which were inaccurate.]

Within this overall process of social transformation, it was increasingly argued that class boundaries were becoming more indistinct and that the more affluent sections of the working class were actually experiencing a process of embourgeoisement; that is they were increasingly becoming middle class both in terms of standard of living, life style and attitudes and values. The supporters of the embougeoisement theory made several inter-related points in support of the theory. Thus, proponents of the embourgeoisement theory made the following interconnected arguments.

- The occupational structure was changing with a decline in the proportion of unskilled and semi-skilled manual jobs and a growth of skilled non-manual and skilled manual jobs, linked to some extent to the relative decline of manufacturing and the increased importance of service industries, a trend which would accelerate in the future.

- The distribution of income and wealth was becoming more equal, partly because of the full employment of the long post-war economic boom and that affluent manual workers now enjoyed living standards comparable to some non-manual workers. Ownership of consumer durables was becoming more widespread and many working class people could now afford holidays abroad.

- Skilled manual workers were now less likely to experience alienation at work and were more likely to be consulted by management. Blauner 's work on the relationship between alienation and changing levels of technology was sometimes used to support this argument.

- Traditional working class communities were declining, and that increasingly geographically mobile manual workers were becoming indistinguishable from their middle class neighbours.

- Equality of educational opportunity was becoming a reality and that manual workers now took more interest in their children's education indicating a reduction in class differences in attitudes to education.

- These trends helped to explain why Labour was defeated in 3 successive General Elections in 1951, 1955 and 1959. Since manual workers were becoming more "middle class" they were deserting the working class Labour Party for the middle class Conservative Party. This could be taken to imply that for these workers there had occurred a decline in working class consciousness.

Consequently, it was argued that the overall class structure was changing from a triangle to a diamond with an increasing proportion of the population falling into the middle range of the stratification system. In this "middle mass society", the mass of the population was middle class rather than working class.

It was also pointed out that insofar as the theory of Embourgeoisement was accurate, it appeared to invalidate at least the more simplistic accounts of Marxist theory which present Marx as a fairly rigid economic determinist predicting that class polarisation would lead to the disappearance of the intermediate strata. By contrast writers such as Clark Kerr argued that technological developments in industrial societies, whether capitalist or communist would require and increasingly well educated, well trained work force earning the high wages necessary to create the consumer demand for the ever increasing production of goods and services possible in industrial economies. As a result, Kerr expected a convergence of capitalist and communist societies in which ideological factors became less significant (due to the so-called end of ideology theory associated with Daniel Bell) as both capitalist and communist societies would be influenced by a by the logic of industrialism which would cause societies to develop in ways not at all predicted by Marx.

However, in his later work, Marx did recognise that the intermediate strata would expand, and it has often been suggested that some of his critics overstated the extent of economic determinism present in his work. Also, Kerr's theory of the logic of industrialism attracted criticism as significant economic and ideological differences remained as between capitalist and communist regimes although notions of convergence and the end of ideology took on a new lease of life with the "collapse of communism 1989-1991), signalling what Francis Fukuyama has called "The End of History." Once again Fukuyama's views have attracted criticism, but I shall not pursue them here. Let us return instead to the nature of the working class!

- Criticism of the Embourgeoisement Theory

In his Dictionary of Sociology, Gordon Marshall states that "the clearest statement of the Embourgeoisement theory is found In F. Zweig's "The Worker in an Affluent Society (1961) which has the virtue that it is empirically grounded since Zweig conducted interviews with workers in 5 British firms." More critically, Marshall further states that "most other proponents of embourgeoisement argued principally on the basis of speculation and anecdote."

In the UK, the Embourgeoisement theory soon came in for heavy criticism and for several reasons.

- Economists pointed out that the distribution of income and wealth in the 1950s was more unequal than had been supposed and it was shown that relative poverty was widespread as was inequality of education opportunity.

- Blauner's theory of the relationships between alienation and levels of technology was criticised on the grounds that was empirically inaccurate in its own terms and in any case that it relied on a narrow definition of alienation.

More specifically in "The Affluent Worker" studies, Goldthorpe, Lockwood, Bechhofer and Platt attempted to analyse the class position of affluent manual workers clerical workers and members of the traditional working class in detail. The authors studied 229 affluent manual workers and their families together with 54 clerical workers for comparative purposes. Luton was chosen as the location for the study because it was seen as an area especially likely to give rise to Embourgeoisement such that Goldthorpe et al. believed that they could conclude that if embourgeoisement was not occurring in Luton it would be unlikely that it was occurring in other parts of the country.

However, Goldthorpe and co. concluded that the affluent workers interviewed in their study had not experienced a process of embourgeoisement although they differed in important respects from both the proletarian traditionalist and deferential traditionalist sections of the working class as well as from the middle class., How did Goldthorpe, Lockwood et al. reach this conclusion?

- Firstly, it was necessary to define "social class" and the authors argued that social class contained economic, relational, and normative aspects. They then argued that the affluent manual workers could not be described as economically middle class because although in some cases they earned more than routine non-manual workers, this was because of overtime or shift work bonuses and that overtime and shift work interfered with their leisure activities and even, in some cases, with their health. Also, they experienced poorer working conditions and enjoyed few if any of the fringe benefits enjoyed by routine non-manual workers. These workers were committed to their company and job only insofar as it provided relatively high incomes. they were not interested in promotion and had few friends at work

- Neither were affluent manual workers middle class in relational terms. They had few middle class friends and were unlikely to engage in typically middle class leisure activities but their leisure activities, far from being community-centred as in the traditional working class, were described as home centred and privatised

- Neither were the affluent manual workers middle class in normative terms. To analyse the attitudes and values of the affluent manual workers it was important for Goldthorpe, Lockwood et al. to be able to compare them with the assumed attitudes and values of the so-called traditional working class and of the middle class. To achieve this, based on the limited evidence available at the time, Goldthorpe, Lockwood and co. relied on previous work by David Lockwood in which he had constructed what he described as ideal-typical proletarian traditionalist and middle class images of society. He also referred to a deferential traditionalist image of society, but this was not deemed relevant for the Luton Study

- Goldthorpe and co. then argued that the affluent manual workers of Luton differed in terms of their attitudes and values from both proletarian traditionalist and middle class workers Thus It was also claimed that they broadly accepted a "money Model" of society rather than the us- them model or the hierarchical model associated with the traditional working class and the middle class respectively. You may click here for further information on working class and middle class images of society.

- Affluent manual workers hoped to improve their living standards not via individual promotion and upward social mobility but collectively via their membership of trades unions and support for the Labour Party. In this they were significantly different from the middle class proper.

- However, they also differed from the traditional working class because although they were highly likely to be members of trade unions and to vote Labour: (80% of the sample had done so in1959), their reasons for so doing were explained by Goldthorpe and CO in terms of instrumental collectivism rather than the solidaristic collectivism associated with the traditional working class. That is: they supported the Trades Unions and the Labour Party not out of a sense of class solidarity but because of a calculated belief that this was the best way to improve their own economic circumstances. .Also, their support for the Labour Party was potentially volatile in that they said that they could easily imagine themselves voting Conservative if Conservative policies appeared more likely to benefit them economically.

In sum, Goldthorpe and CO claimed to have uncovered not a process of Embourgeoisement but the emergence of a "new working class whose work experience, life styles, attitudes and values, although different from those of the traditional working class, were, nevertheless, still recognisably working class. They argued also that a process of "normative convergence" between the "new working class and the clerical workers was underway as clerical workers also increasingly joined trade unions attempting to halt the relative decline in their living standards

This is a widely respected study of an important aspect of the 1960s class structure, but it has been subjected to several important criticisms. In 'In Praise of Sociology' (1990), Gordon Marshall, while complimenting the Goldthorpe et al study, also refers to several criticisms which have been made of it since its publication. Thus, among the criticisms noted by Marshall are the following.

i). It is argued that within the traditional working class there have existed so-called proletarian traditionalists (who have been very critical of employer-employee relationships as being based on exploitation and conflict) and deferential traditionalists (more prepared to accept the current employer-employee and, indeed, more likely to be Conservative). It is then argued that the new working class identified in the Goldthorpe-Lockwood study are indeed a new phenomenon different from both types of traditional working class. However, this point may be criticised in that it is not at all certain that the traditional working class perspectives as described are any more than theoretical constructs which may not exist in practice. Also, it is claimed, there may be nothing new about the so-called new working-class. Marshall comments... "the well-documented privatism and instrumentalism of the skilled workers of the mid-Victorian labour aristocracy suggests that these attitudinal and behavioural traits are not peculiar to the post war period and may always have been close to the surface of working class life".

ii). Although it may be difficult to fault the Goldthorpe, Lockwood methodology, it may still be true that there may have been more working class solidarity and job interest among the Luton workers, but the survey methods were unable to pick them up.

iii). It is claimed that Goldthorpe, Lockwood and co. asked many, many questions, and sometimes received contradictory answers, but may sometimes have under-emphasised some of the contradictory evidence in order to justify the theories they were putting forward. Marshall comments "the finding that 52% of workers agree unions should be just as concerned with getting higher pay and better conditions while only 40% agree that they should also try to get workers a say in management, scarcely seems to justify the conclusion that there is no widespread desire among these men that their unions should strive to give them a larger role in the actual running of the plant".

iv). It is also argued that Goldthorpe and Lockwood tended to romanticise the so-called companionate marriages of the Luton workers. Feminists, for example would argue that such marriages were based very heavily on power inequality and would cast some doubt on how fulfilling the marriages were.

v). Very straightforwardly, it has been pointed out that the sample of clerical workers was very small (54) and therefore, not necessarily representative.

vi). Also, the affluent manual workers were all aged between 21-46 and all married. They may have been home-centred because many of them had young families, rather than because they were members of a new working class.

There are other criticisms of the Goldthorpe, Lockwood study, but these which have been given above are sufficient to suggest that although the Embourgeoisement theory was heavily discredited, Goldthorpe and Lockwood's own approach to the study of the development of the working class is also not without its critics.

Click here for a detailed article by Professor Mike Savage: Working class identities in the 1960s: revisiting the affluent worker study [2005] in which he suggests that many Luton manual workers were conscious of divisions between themselves and a political and economic elite , much as was suggested in the proletarian traditionalist image of society.

Social Class in Modern Britain [ G. Marshall, David Rose, Howard Newby, and Carolyn Vogler 1988]

Throughout the 1980s it was increasingly argued that the working class had become increasingly fragmentary. Ivor Crewe had pointed to the implications for voting behaviour of the distinction between the old and the new working class while P. Dunleavy and C. Husbands in their study "British Democracy at the Crossroads" [1985] argued that class dealignment occurred because of the growth of sectoral cleavages within both the working class and the middle class as between public sector and private sector workers and between consumers of publicly and privately provided housing, health care, education and transport. Public sector workers and consumers of publicly provided services are more likely to Labour because they perceive Labour as the party most likely to improve public sector pay and conditions and to improve public services while private sector workers and consumers of privately provided services may be more likely to vote Conservative because they oppose the higher levels of taxation necessary to defend public service employment and the expansion of public services which they do not use.

Social Class in Modern Britain is a detailed study of several aspects of the UK class structure based upon 1770 interviews carried out in 1984 in which the authors assess the relative usefulness of the NS SEC schema and the E.O. Wright schema for the analysis of the UK class structure, and they also present information on social mobility, proletarianisation and voting behaviour. However, I shall attempt here only to summarise some of their comments on class identity, class awareness and the potential for class-based political action which are relevant to the consideration of the embourgeoisement theory.

The authors note that it was widely claimed in the 1980s that the UK class structure was becoming increasingly fragmented. Due to the increased role of pension funds and other financial institutions in the ownership of capital it was more difficult to visualise a recognisable capitalist class and there were also increasing divisions within the middle and working classes. Thus, the working class were seen as divided between workers in well-paid, secure jobs often in Southern England in expanding industries compared with their opposite; between skilled and unskilled workers; between workers in the public and in the private sector; between trade union members and non- trade union members; between employed workers and those dependent on state benefits. Further divisions based on age, disability, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality existed within the working class all of which may lead to differences in interests, attitudes, and behaviour.

It was also suggested that within the working class in the era of Thatcherism the instrumental collectivism and privatism identified in the Goldthorpe -Lockwood Luton study had intensified, and that working class people were now unlikely to identify with broad political struggles against unemployment, economic inequality, or nuclear weapons and more likely to seek solace in a privatised family life style.

However, based on their survey data Marshall and his colleagues conclude that individuals of all social classes are still highly likely to identify with membership of a social class rather with any other social grouping and that there is also a widespread belief throughout the class structure that there is too much social and economic inequality and that governments should do more to reduce these inequalities. However, it is also widely believed that it should be possible to reduce these social and economic inequalities via reforms within the capitalist system rather than via the abolition of that system although there is also a widespread cynicism that all political parties are the same and that none are likely to take meaningful action to increase social and economic equality. Thus, the authors draw the important conclusion that it is a resigned cynical fatalism as to the ineffectiveness of all political parties rather than a growth of individualised self-interested egoism which has stimulated the instrumentally collectivist approach to politics which had been recognised in the Goldthorpe- Lockwood study.

There are some similarities between the conclusions of this study and those of Fiona Devine’s 1992 study reassessment of the Goldthorpe-Lockwood Luton study as is indicated below.

Affluent Workers Revisited: Privatism and the Working Class: Fiona Devine 1992

In her study “Affluent Workers Revisited: Privatism and the Working Class” [1992] Fiona Devine conducted a detailed study of 62 Luton residents of Vauxhall workers and their wives. Her main aim was to reassess the main conclusion of the original Affluent Workers studies conducted by Goldthorpe, Lockwood, Bechhofer and Platt [GLBP] in the early 1960s which had essentially discredited the Embourgeoisement theory and some later studies such as those of I. Crewe, P. Dunleavy and C. Husbands and P. Saunders which, according to Fiona Devine involved a “revival of all or part of the embourgeoisement thesis.”

Fiona Devine concludes that the experiences, attitudes, and values of her respondents differed in several important respects from those of the respondents in the original Affluent Worker studies although she emphasises thar this cannot be taken as a direct refutation of the original studies which of course referred to different people at an earlier time and that the conclusions of her small- scale study can be assumed to be representative of working class people in general.

The key conclusions of her study may be summarised as follows.

Whereas many of the respondents in the GLBP study had moved to Luton in search of the relatively high wages which were available there in the early 1960s, respondents in Fiona Devine’s study had often moved to escape the higher rates of unemployment prevalent in the less prosperous regions or to purchase house at lower prices than those prevalent in the rest of the South East.

Also. in several cases they hard kin and/or friends who had already moved to Luton which meant that they were less likely to adopt the privatised, family centred life styles which had been reported in the original Affluent Worker studies. She found also that males were likely to socialise in the community with kin and with neighbours who might also be workmates and that females often relied on extended kin and neighbours for help with childcare.

However. her respondents were restricted in their leisure activities by the demands of paid work and relatively low wages and by the responsibilities of housework and childcare which remained mainly the responsibilities of wives rather than husbands. Patterns of sociability were also significantly affected by the changing stages of family life and both males and females had greater opportunities for community sociability once their children were older. Thus. the lifestyles of Fiona Devine’s respondents were neither entirely privatised nor entirely community centred and were related more to the demands of paid employment and childcare and to the changing stages of family life rather than to a shift toward greater individualism which had been emphasised in the original GLBP studies.

In the original Luton studies GLBP attempted to analyse affluent workers’ images of society and concluded that whereas so-called proletarian traditionalists operated with a conflict based two class dichotomous model of the class structure and middle class workers favoured a more graduated ladder=type model of society, affluent workers operated with a three class money model of society containing a small upper class, a small lower class and a large middle class containing professional workers but also workers like themselves. The working class respondents in Fiona Devine’ s study operated with a similar money model of society, but they emphasised that in their view this class system was essentially unfair because the privileged upper class could enjoy much higher living standards without having to work hard to attain them whereas for the large middle class and the smaller lower class the reverse was the case.

The workers in the Devine study hoped to improve their living standards through their own efforts but they also identified with other members of their class and hoped that they too would be able to attain the higher living standards which they deserved. Thus, whereas in the original Luton study affluent workers were characterised by an instrumental collectivism in that they hoped that support for the Labour Party and the Trade unions would enable them to improve their own living standards, the workers in the Devine study retained a sympathy with the plight of other members of their class. These workers also believed that the Labour Party and the Trade Unions should help to further working class interests, but they were in many cases disillusioned by the failure of the Labour Party and the Trade Unions to do so. Respondents in the study spoke of the bureaucratic inefficiencies of the trade union movement and doubted the ability of the Labour Party to manage the economy effectively as a result of which the party would be unable to fulfil its promises to expand the provisions of the welfare state. The respondents therefore tended to believe that the family life cycle was a key determinant of living standards which would improve if and when children started work or left home to live independently.

Whereas in the Goldthorpe, Lockwood, Bechhofer and Platt study of the 1960s support for the Labour Party remained high among the “new Working class” [ 80% of whom had voted Labour in the 1959 General Election] in the Fiona Devine study, working class support for Labour was much lower: out of 62 respondents 24 were Labour Party supporters, 24 were disillusioned Labour Party supporters and 14 were non-Labour Party supporters. This was unsurprising since there was now very clear evidence that at the national level in the late 1980s and early 1990s working class support for Labour was much lower than it had been in the 1960s.

Also, it has been argued that the 1980s saw the beginnings of the development of an "underclass" in the UK whose living standards and opportunities are significantly worse than those of the working class as a whole. Here sociologists have distinguished between structural and cultural variants of Underclass Theory. Structural views of the theory maintain that an underclass has developed because of changes in the structure of the world economy, resulting in the de-industrialisation of capitalist economies and mass unemployment caused by the relocation of manufacturing production to developing economies with lower labour costs. On the other hand, in cultural versions of the theory, underclass membership is said to derive from the development of dependency culture deriving from excessive expansion of welfare state support which needs to be cut back if the growth of the underclass is to be reversed.

It is true that some sections of the working class are severely disadvantaged, but critics of the Underclass Theory argue that these disadvantaged groups are still visibly part of the working class as a whole. There has also been especial criticism of Charles Murray's variant of the Underclass Theory in which he explains the persistence of the underclass in terms of the cultural pathology of its members rather than in terms of wider structural factors which inhibit opportunities for disadvantaged groups no matter how hard they may try to improve their situation. Whether or not an underclass exists, the existence of mass relative poverty has major implications for the analysis of the UK class structure. I hope to provide further information on Underclass Theory in a subsequent document

Most recently, further fragmentation of the working class and of the class structure in general has been evident in Scotland as attitudes to Scottish independence divided the social classes, and in the UK as attitudes to Brexit divided the class structure with absolutely monumental political consequences. I shall not consider these political issues here but merely reiterate that analysis of the working class from a mainly Weberian perspective has certainly emphasised the increasingly fragmentary nature of the working class.

Marxists may well continue to emphasise the importance of the fundamental economic exploitation experienced by all members of the working class, but it certainly does appear that the divisions within the working class emphasised by Weberian sociologists have had major effects on the attitudes and behaviour of working-class people. However, although the Weberians emphasise class fragmentation, there is nothing in these Weberian theories to suggest that the UK is becoming increasingly classless.

6.3. The Oxford Social Mobility Study and the subsequent development of the UK NS SEC class schema

In their study Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain, John Goldthorpe and his associates developed an essentially neo-Weberian model of the British class structure to investigate patterns of social mobility in England and Wales. For purposes of the study, a 7-class schema based upon differences in market situation and work situation was developed, where market situation referred to “respondents' sources and levels of income, their degree of economic security and chances of economic advancement”, and work situation referred to "their location within the systems of authority and control governing the processes of production in which they were engaged and hence in their degree of autonomy in performing their work tasks and roles”.

Goldthorpe and his associates subsequently made some modifications to this schema and came to use a class schema based upon a combination of employment status [distinguishing between employers, the self-employed and employees] and different forms of employment regulation [service contract, labour contract and intermediate contract] [see below].

The Goldthorpe schema was subsequently adopted with some further modifications to form the basis of a new official system for the analysis of social-class membership known as the NS SEC Classification, which was introduced in 2001. The precise details of the current version of the NS SEC Classification are complex and may be found via the following link.

Click here for a full description of NS SEC Categories as of 2016, and Click here for a letter on social classes comparing the NS SEC schema and the GBCS Schema. I present below some of the main points from this publication.

- The NS-SEC is an employment-based classification, but it can also be used to provide coverage of the whole population via the allocation of pensioners to appropriate NS SEC classes on the basis of their previous employment and the introduction of further separate categories for students, the unemployed and those who have never worked.

- Individuals' allocation to their appropriate NS SEC classes depends upon their employment status: whether they are an employer, self-employed or employee, whether a supervisor, and upon the number of employees in their work place.

- Individuals' employment situations are classified in terms of their labour market situation, their work situation and the nature of their employment contract.

- "Labour Market situation equates to source of income, economic security and prospects of economic advancement", and "Work situation refers primarily to location in systems of authority and control at work although degree of autonomy is a secondary aspect.”

- The NS SEC also distinguishes 3 forms of employment contract. This is explained in the above publication as follows:

- "Service relationship: the employee renders service to the employer in return for remuneration which can be both immediate reward [for example salary] and long term prospective benefits [for example assured security and career opportunities]. The Service relationship typifies Class I and is also present in weaker form in Class 2.

- Labour contract: the employee gives discrete amounts of labour in return for a wage calculated on the amount of work done or time worked. The labour contract is typical of Class 7 and in weaker form in Classes 5 and 6

- Intermediate: these forms of employment regulation combine aspects from both the service relationship and labour contract and are typical of Class 3."

It is then argued that individual occupations can be classified in terms of the different types of employment contract attaching to them and therefore be allocated to appropriate occupational classes within the NS SEC schema. Some examples are provided in the table below.

The NS SEC data can be presented in several differing formats, as is indicated in the document mentioned above, which refers to the following schema:

- a schema based on 8 analytic classes.

- a schema based on 16 operational categories and sub-categories.

- "collapses" of the 8 analytic classes schema into 5 categories and 3 categories.

The most frequent presentation is in terms of 7 NS SEC classes combined with an 8th category for those who are long-term unemployed or have never worked. Also, in some formats data are included on full-time students and those whose occupational status cannot be classified.

Data based upon the 5 class categorisation are presented below and analysts also sometimes refer to a 3 class categorisation comprising the Service Class (NS SEC Classes 1 and 2), the Intermediate Classes [NS SEC class 3, 4 and 5) and the Working Class [NS SEC Classes 6 and7)

Some Recent NS SEC data

Click here, and then in the table of contents click on Section 8: National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS SEC) for data on the NS SEC in the 2011 Census, subdivided according to Gender.

More detailed data on the distribution of individuals in the 2011 Census to the NS SEC social classes can be found here and here. I have used this source for my own calculations which appear in the following table. (The 2011 Census column calculations do not add up to 100% because of the inclusion of subdivisions of Categories 1 and 8 and also because of rounding.)

Click here and scroll down to Section 4 for NS SEC data for England and Wales from the 2021 Census. Note that since the 2001 and 2011 data refer to the UK and the 2021 data refer to England and Wales, the data are not fully comparable, but they do give some idea of recent changes in class structure as measured via the NS SEC Schema.

In relation to the NS SEC data it is important to note the following points:

- In Weber's original 4-class scheme, one social class contained property owners, and insofar as neither the original Goldthorpe schema nor the NS SEC schema includes a separate NS SEC class of property owners, they could to some extent be seen as departures from the Weberian 4-class schema.

- Since the NS SEC schema is based upon employment status and occupation, it does not include as a separate class category of individuals who are independently wealthy and have no employment status or occupation. However, information is available here on the distribution of wealth related to the NS SEC categories; although, as expected, members of NS SEC Class 1 are most likely to own high levels of wealth, there are some very wealthy individuals among the never-worked or long-term unemployed category.

- It should be noted that although the NS SEC schema is based upon employment status and occupation, it is not based in any way on the levels of skill associated with individual occupations, as was the case in the previously used Registrar General's Classification.

- The schema is not fully hierarchical in that NS SEC classes 3, 4 and 5 are not listed in hierarchical order.

- No distinction is made between non-manual and manual occupations as was the case in the RG Classification.

- There are no references to the terms upper class, middle class and working class. Click here for an article by Graham Scambler which points to the limitations of the NS SEC [ and subsequently the GBCS] for the analysis of the higher reaches of the UK class structure.

The NS SEC schema has also been used to illustrate the existence of significant social-class differences in educational attainment, as in the Youth Cohort Studies which were unfortunately discontinued in 2007, leading to the far from satisfactory procedure of using eligibility for free school meals as a broad indication of social-class membership. NS SEC data are also used to illustrate the existence of social class differences in enjoyment of good health and in life expectancy.

Click here for the most recent 2017 data on NS-SEC membership and life expectancy, which indicate that for men average (mean) life expectancy in 2017-2018 varied between 82.5 years in Class 1 men to 76.6 years in Class 7 men, and between 85.1 for Class 1 women and 80.8 for Class 7 women.

Thus, for Neo-Weberian sociologists, class inequalities continue to exist and to exercise a major influence on life chances.

The NS SEC Classification and recent trends in the UK class structure

| NS SEC category | Examples of occupations in each

NS SEC category |

2001 Census data % | 2011 Census data % | 2021Census

England and Wales Only |

| 1. Higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations | 11.9 | 10.0 | 13.1 | |

| 1.1 Large employers and higher managerial and administrative occupations | Large employers, chief executives, senior civil servants, financial managers, production managers | 2.3 | ||

| 1.2 Higher professional occupations | Scientists, pharmacists, dentists, university teachers, civil, mechanical and electrical engineers, lawyers | 7.8 | ||

| 2. Lower managerial, administrative and professional occupations | General managers in small companies, lower grade civil servants, nurses, schoolteachers, social workers | 24.2 | 20.7 | 19.9 |

| 3. Intermediate occupations | Clerical workers, library assistants, nursery nurses, secretaries | 12.5 | 12.7 | 11.4 |

| 4. Small employers and own account workers | Shopkeepers, publicans, electricians, plumbers, builders | 9.1 | 9.2 | 10.6 |

| 5. Lower supervisory and technical occupations | Foremen, supervisors, laboratory technicians, printers | 9.4 | 7.0 | 5.4 |

| 6. Semi-routine occupations | Chefs, cooks, fitters, sales assistants, care assistants | 15.5 | 14.2 | 11.4 |

| 7. Routine occupations | Bar staff, bus drivers, cleaners, refuse collectors, warehouse workers | 12.3 | 11.3 | 12.1 |

| 8. Never worked and long-term unemployed | 5.0 | 5.6 | 8.5 | |

| L14.1 Never worked | 3.8 | |||

| L14.2 Long-term unemployed | 1.8 | |||

| L15 Full-time students | 9.0 | 7.5 |

The NS SEC and Long-term Changes in the UK Class Structure

In the following diagrams the original NS SEC categories have been collapsed into 5 categories and estimates have been made for the distributions of individuals among these 5 categories prior to 2001, which is when the NS SEC Classification was first introduced. It is clear that since 1951 the proportions of male and female workers in the Managerial and Professional category have increased, and the proportions of male and female workers in the routine and semi-routine occupations have declined. The proportion of female workers in the intermediate occupations has declined, but it remains higher than the proportion of males in these occupations.

| Male labour force by occupational class 1951-2016

Census and 2016 Annual Population Survey

|

Female labour force by occupational class 1951-2016

Census and 2016 Annual Population Survey

|

|

|

We may conclude that although Neo-Weberian theorists point to the increasingly fragmentary nature of the UK class structure and dispute classical Marxist theories of working-class revolution, they do not suggest that the UK is in the process of becoming an increasingly classless society.

For Part 4 - Click Here