Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Section 4:

For next part Essay Click here Is your Brain Male or female Also here and here for lost boys

Possible Explanations of Gender Differences in Subject Choice:

Please note that I have currently written 7 essays on the Sociology of Education and intent to write a few more in the near future. Note that in each case these essays are far longer than could be written under examination conditions and that although they include points of knowledge , application and evaluation I tend to use separate paragraphs for each of these categories rather than to combine several categories in each paragraph as in the strongly recommended PEEEL approach whereby each paragraph should include Point; Explanation, Example: Evaluation and Link to following Paragraph.

I hope that you find the information in these essays useful but would strongly recommend that you write your own essays using the PEEEL approach or something very similar to it. Obviously, your teachers will advise you as to appropriate essay writing technique.

Essay: Gender Differences in Subject Entry

Essay revised: April 2023

In many past societies men and women have performed significantly different social roles and despite a range of economic, political and social changes such differences persist to a considerable extent in the contemporary world. For example in the case of the UK women are still more likely than men to take disproportionate responsibility for childcare and housework; they are more likely to opt for some types of employment than others ;their overall ir employment opportunities, although improving, are still worse than men’s and although they finally gained the right to vote in 1928 they are still much less likely than men to become local councillors, MPs or government ministers. There has been great controversy surrounding the extent to which these differences in social roles are explicable by biological sexual differences or by gender differences which are socially constructed rather than biologically determined.

It has been claimed that gender differences in childcare and housework responsibilities and in employment patterns derive from gender differences in hormonal balance, from biologically determined differences in physical strength and competitiveness and from women’s biologically determined maternal instincts. It has even been argued in the past that because males have larger brains, they are on average more intelligent than females and that differing aptitudes and skills between males and females can be explained partly by differences in brain shape which mean that on average males have greater spatial awareness and numerical ability and that females have greater verbal reasoning skills and writing ability.

Click here and here for articles related to this type of theory which you may discuss with your teachers. The second article summarises some of the findings from a recent episode from a BBC Horizon programme which unfortunately no longer available. For more detailed discussion Click here for Sexing the Brain and here for Is the Brain Gendered? Also Click here for a critical discussion of such views.

However sociologists are much more likely to argue that gender differences in social roles are mainly socially constructed and they have claimed that in societies such as the UK the socialization process as it operated at least up to the 1970s meant that many parents socialized their daughters to show dependence, obedience, conformity and domesticity whereas boys were encouraged to be dominant, competitive and self -reliant At an early age girls might well be encouraged to play with dolls while boys might be encouraged to embark on tasks such helping with gardening or cleaning the family car and also when young children saw their parents acting out traditional gender roles it was likely that in many cases they would come to see these roles as natural and inevitable. Thus, it has been argued that even before they began school boys and girls would become conscious of their differing gender domains which encapsulate the differing tasks, activities attitudes and values which are associated with males and females respectively and would "feel comfortable" primary when they feel they are acting in accordance with their respective gender domains.

Furthermore gender differences in socialisation would continue in schools as teachers generally praised girls for "feminine qualities" and boys for "masculine qualities" and both boys and girls could expect criticism and ridicule from their peer groups if they acted other in accordance with their gender domain. . Furthermore, in the mass media girls were encouraged to recognize all =importance of physical attractiveness, finding "Mr. Right" and settling down to a life of blissful domesticity in their traditional housewife-mother roles. Boys and girls were encouraged to opt for traditional male and female subjects to a considerable extent because they were expected to opt for traditional male and female careers.

The 1976 study by Sue Sharpe could be used to explain gender differences in attitudes to education in general in terms of gender differences in socialisation and the differing employment aspirations and opportunities available to males and females. Thus she argued on the basis of a study of 15-16 year old girls that they saw their futures more in terms of marriage and motherhood rather than an permanent employment career but also that they had rejected many potential careers because they had been socialised via family , school and mass media to regard them as traditional male careers and therefore inconsistent with their image of femininity and/or because they also recognised that employers would in any case be unlikely to employ females in such positions. Thus, if they were intending to leave school at age 16, they were especially likely to opt for secretarial or retailing or light assembly work and if they were intending to continue their education, they were most likely to opt for the caring profession such as nursing, teaching or social work which were widely believed to be in accordance with females' inborn nurturing qualities.

However it has been pointed out that from then 1950s to the 1980s gender differences in subject entry at GCE Ordinary Level were actually fairly limited in that 8 or 9 of the most popular O Level/GCSE subjects were roughly the same for boys and girls although there have been some differences in the rank order of the different subjects. Also at this time boys were typically more likely than girls to opt for Physics, Chemistry, PE, Craft and Technology while girls were more likely to opt for Domestic Science and Religious Studies.,

Also gender differences in the allocation to practical subjects at CSE level and in non-examination courses may well have been greater. Boys were highly likely to be entered for the handicraft subjects which would prepare them for entry into traditional male skilled manual work. Very few girls. in the 1970s would have aspired to careers as say, motor mechanics, plumbers, bricklayers or electricians and even if they so aspire did would usually have been dissuaded by the realisation that they were highly likely to face gender discrimination if they sought these types of employment. Instead, they routinely opted for domestic science and childcare to prepare themselves for marriage and motherhood sometimes combined with routine office skills courses to prepare themselves for secretarial work or retailing.

Once the GCSE replaced the GCE and CSE examinations from 1986 [for first examination in 1988] gender differences in subject entry were again small in relation to the 10 most entered GCSE subjects although there were some significant gender differences in subject choice especially in relation to subjects geared to careers which were seen as traditionally male or traditionally female. For 2019 relationships between gender and GCSE subject choice may be summarised as follows [although you will need to discuss with your teachers how these statistics might be used much more concisely for examination purposes.!!]

6 Possible Conclusions

|

Although as stated above gender differences in subject entry in the main GCE/GCSE subjects had been fairly small sociologists especially from f the 1980s onwards sociologists had voiced concerns especially in relation to the effects of schools themselves in encouraging stereotypical option choices and limiting girls' access to the Natural Sciences. Thus, it was argued by Teresa Grafton and co. [1987] based on a study of one co-educational comprehensive school in the South West of England that the schools themselves in the 1980s were encouraging traditional gender differences in subject choices which reflected the gender division of labour in society generally. There were limited places for boys and girls in non-traditional craft options and subject advice given by teachers reflected traditional views as to the "appropriate" gender division of labour. However, as would be expected, the researchers found also that subject choices were affected also by the gender division of labour in the home and in the labour market.

Alison Kelly [1987] attempted to analyse why female students were less likely to opt for sciences other than Biology. She argued that girls often felt at a disadvantage in Science lessons because textbooks and teaching examples tended to reflect male rather than female interests; because science teachers tended to be male and to relate more easily to boys; and because boys tended to monopolise equipment and class discussion. These factors could combine to cause an ongoing decline in girls' enrolments in sciences other than Biology, but they did not apply to Biology which was seen by girls as more relevant to their preferred career options, for example as nurses, and to their likely future as housewives and mothers. [Notice however that this study was undertaken before the National Curriculum was introduced and Science became a compulsory subject at GCSE Level such that from 1988 onwards more or less equal numbers of boys and girls would study the Sciences at GCSE Level]

Initiatives such as GIST [Girls into Science and Technology] and WISE [Women into Science and Engineering] were begun in the late 1970s and early 1980s in an attempt to encourage female students to study Science and Engineering subjects although the effectiveness of these initiatives should not be overstated. In the GIST programme [1979-1983] researchers worked in 10 co-educational comprehensive schools to try to raise teacher awareness of equal opportunities issues and to encourage more girls to opt for Sciences at GCE and CSE levels. The final report concluded that the initiative had improved girls' attitudes to Science and Technology; that it had nevertheless had little impact on subject choice; and that the teachers, although sympathetic to the programme, said that they had not modified their teaching practices substantially as a result. However, the GIST initiative could be regarded as an early pilot programme which has encouraged many subsequent equal opportunities initiatives. [The WISE programme was set up as a national initiative by the Equal Opportunities Commission and the Engineering Council and was designed to raise awareness of the need for more female scientists and technologists and to emphasise the attractiveness for girls, young women and older women seeking to retrain of careers in Science and Technology. WISE is still in operation and its website points out that whereas about 20 years ago only 4% of Engineering undergraduates were women the figure for 2009 was 13%. Obviously WISE itself may well have contributed to this increase at least to some extent.]

You may click here for latest data from WISE [September 2023] and Click here for further very detailed data on the current employment of female STEM Professionals.

As mentioned above when the National Curriculum was introduced in 1988 English Maths and Science all became compulsory subjects at GCSE level and most schools entered males and females in very similar proportions for the Double Science Award although there remained significant gender differences in entry for separate GCSE courses in Physics, Chemistry [ more boys] and Biology [more girls] and boys were also more likely than girls to study GCSE options such as Economics , Information Technology and Computing. Thus Anne Colley [1998] argued that despite the introduction of the National Curriculum girls were still being dissuaded from opting for Science and Technology subjects. She claimed that the images of the instrumental male and the expressive female [suggested, as you will doubtless recall, by Talcott Parsons in the 1950s] still exercise a considerable hold over male and female attitudes ; that Computing [or Information Technology] especially continues to be taught in ways more appealing to boys than girls and that girls are more successful in Maths and Science when they are taught in all-girls schools or in single sex classes in coeducational schools .[I shall provide some further information below on the issue of single sex education]

The above mentioned studies of Alison Kelly [1987] and Anne Colley [ 1998] suggested that there were aspects of GCSE Ordinary Level and GCSE teaching of Science and Technology subjects which may well have dissuaded females from opting for these subjects at Advanced Level even when they were successful at GCSE level. It may be that the GIST and WISE [see above] programmes addressed these issues to some extent but that further initiatives are necessary to encourage females to opt for Science and Technology subjects at Advanced Level There is evidence that even when females have gained high grade GCSE passes in the Sciences they are not necessarily confident in their abilities in these subjects. Click here for a Guardian article on why girls who achieve good GCSE results in STEM subjects are nevertheless less likely than boys to choose them as A Level options and Click here

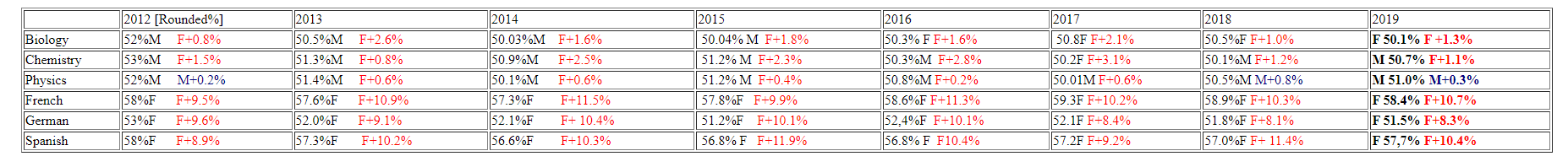

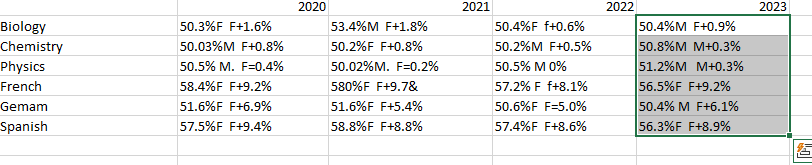

In more recent years gender differences in entry for single science subjects at GCSE Level have narrowed very significantly. In the following table the black figures illustrate the male or female majority of subject entrants and the red [female] or blue [male] figures illustrate the gender gap in attainment of A*-C or 9-4 GCSE grades. It should be noted that traditionally larger percentages of entrants for individual Sciences have been males but that these gender gaps have narrowed appreciably in recent years and since 2015 female entrants have exceeded male entrants in Biology and this was also the case in Chemistry in 2017 and 2021 and. Male entrants continue to narrowly exceed female entrants in Physics. Note that Female pass rates have narrowly exceeded Male pass rates in Biology, Chemistry and Physics in every year except for Physics in 2012, 2018, 2019, and 2022.

GCSE Science and Languages Results 2012- 2019

Thus the most recent data indicate that gender differences in entry for single science GCSE courses are negligible but the data indicate that that males were significantly more likely than females to opt for Economics, PE, Business Studies, ICT, Construction, Technology [excluding Design and Technology] and Engineering while females were much more to opt for Social Science, Drama, Health and Social Care , Home Economics and Performing Arts. At the extremes in 2019 89.6% of Engineering entrants were male and 98.7% of Home Economics entrants were female. Gender differences in subject entry were substantial also in French [+57.3%F] and Spanish[+56.6%F] but not in German [+52.1%F]

Students may click here to access the 2022 data. Click on GCSE and Other Results Information and then scroll down to GCSE Additional Charts Summer 2022

In her 1987 study Alison Kelly had suggested a variety of reasons why females were less likely to opt for Natural Sciences subjects at GCE O Level and CSE Level but nowadays gender differences in entry for Double Science and the Individual Sciences at GCSE level are negligible . However in 2017 the Institute for Fiscal Studies conducted an analysis of the factors limiting female entries for Advanced Level Mathematics and Advanced Level Physics which explained the relatively low entry of Females for Advanced Level Physics among females who were predicted to gain Grade 7 or higher in GCSE Science examinations] in terms of the same factors as had been suggested by Alison Kelly and by Ann Colley [1998] in relation to GCSE Science and Technology subjects.

Gender and Subject Choice: GCE Advanced level

When Sue Sharpe repeated her 1976 study in 1994 female employment opportunities had improved, traditional gender differences in socialisation were weakening and she found that girls expressed more interest in careers in general and they have since the 1990s been increasingly likely to enrol on GCE Advanced level and Degree courses and to seek employment in professional and managerial occupations. In her study[2000] of 50 girls and 50 boys in years 10 and 11 at 3 London comprehensive schools Becky Francis found that the girls in her sample expressed interest in a relatively wide variety of careers; were relatively unlikely to favour stereotypical female careers such as nurse, clerical worker or air hostess ; were quite likely to express interest in careers usually associated with men and very likely to express interest in careers for which further education, higher education and a degree will be necessary.

However even in 2019 despite some considerable relative improvement women remain generally under-represented in high status, well-paid professional and managerial occupations relative to men and under-represented especially in some professions such as those related to Mathematics, Physics, Engineering, Computing, Technology, and Architecture. It transpires that gender differences in subject choice at Advanced Level and beyond are greater than at GCSE Level and that these gender differences in subject choice may be seen as both a consequence and a cause of the underrepresentation of women in particular professions.

|

Click here for an article from the Independent [August 2012] which reports recent research suggesting that gender differences in employment intention are still based to a considerable extent of stereotypical views of male and female employment patterns. Click here, here and here for BBC items on women in scientific careers Click here for recent information on proportions of Women in STEM occupations.

Gender differences in subject choice are considerably larger at GCE Advanced Level than at GCSE Level and if anything, such differences are even greater at University Level.

In Section 3B there is some more detailed statistical information on Gender and Subject Choice at GCE Advanced Level. Gender differences in subject entry in the Sciences and Mathematics are considered to be especially important. In summary Females were more likely than Males to opt for Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences [other than Economics] and Biology Males were more likely than females to opt for Mathematics, Further Mathematics Physics, , Other Sciences, Computing, ICT, Economics and Business Studies. These subject choices at Advanced level have important implications for subsequent choices at Higher Education Level and for future careers. It is very important to note , however, that in 2019 Female entries in all Science subjects combined exceeded male entries in all Science subjects combined.

Gender and Vocational and Higher Education. Click here for Section 3c on Vocational and Higher and Vocational Education It is well known that working class male and female students are more likely to be unsuccessful at GCSE level. These students are perhaps also more likely to have been socialised into traditional gender roles and to believe [correctly] that their employment prospects, although limited, are best in traditional male and female occupations. Many relatively unsuccessful female students may therefore opt for subjects such as Domestic Science or Health Care partly because they do not infringe traditional views of femininity, partly because of better employment prospects in these areas and partly because the skills gained are seen as being useful for their future roles as housewives/mothers. Relatively unsuccessful boys are likely to opt for Construction and Building, Engineering or Computing and Technology options for much the same reasons. Gender differences in choice of Apprenticeship schemes are very marked and can surely be explained in terms of the ongoing strength of traditional socialisation processes and continuing gender differences in employment opportunities. It could indeed be argued that choices of such schemes have much more power than do A level and Degree level subject choices to confirm or undermine traditional perceptions of femininity and masculinity. Click here and scroll down to table on Personal Characteristics for years 2014/15 to 2022/23 which illustrate gender differences in entry to HE courses 2021. Females predominate in subjects allied to Medicine, Psychology, Social Sciences Languages and in Design and creative and performing arts. Males predominate especially in Engineering and Technology and Computing. Business and Management courses are very popular with both males and females, How are these gender differences in subject choice to be explained? As females came to outperform males in almost all GCSE subjects it was noted that they did so especially in Arts and Humanities whereas Males outperformed narrowly in Mathematics and sometimes in Physics and this led to claims that the gendered variations in examination results in different subjects might be explicable in terms of gender differences in the structures and operations of the brain which enabled females to develop superior linguistic skills and males to develop superior numerical and spatial skills..

Click here and here for short articles and here for a detailed report on Gender and STEM subjects from the IFS 10. Once subjects are strongly perceived as predominantly "male" or predominantly "female" subjects self-fulfilling prophecies may operate as males continue to choose "male" subjects and females continue to choose "female" subjects. 11.In some very significant work Professor Louise Archer has argued that both males’ and females’ choice of Science options at all levels is dependent upon their possession of Science Capital. That is: middle class pupils, and especially those whose parents have a scientific background, are especially likely to opt for science subjects. Click here for Professor Archer’s presentation of this research and Click here for Professor Archer’s presentation on Exploring Young Women’s Stem Aspirations. Click here for the views of Ms Katharine Birbal Singh which attracted some controversy.

12 It has been noted that larger proportions of female students in single sex girls schools than in coeducational schools opt for Advanced level Sciences and it has also be claimed that this is because female students in single sex schools are more strongly encouraged by teachers to consider the possibility of entry into scientifically based professions, that the. teachers approach the teaching of the natural sciences in more female-friendly ways and because the possibility of denigration by male students is removed. A 2013 Report by the Institute of Physics illustrated that in 2011 both in the state sector and in the independent sector girls in single sex schools were much more likely than girls in coeducational schools to take A level Physics. Click here for Guardian article on Closing Doors”. Such comparisons should be treated with some care since it is also argued that female students in single sex schools are more likely to have middle class parents who are more open to the possibility of scientific careers for their daughters and that there may be smaller differences between the subject choices of girls in single sex schools and high performing [ and often but not always middle class] girls in high performing coeducational comprehensive schools. In summary, Females may be more likely than males to opt for Arts, Humanities and some Social Sciences at Advanced Level because they have been more successful than males at GCSE Level partly as a result of superior language skills, because they may feel more comfortable in discussion of the subject matter, because they associate the Arts , Humanities and Social Sciences with career opportunities which are more open to females partly because they have been influenced in these perceptions by parents, teachers and the mass media. Meanwhile they are dissuaded from Mathematics, Physics, , Computing, Technology and Economics because they have been socialised to believe that these are "male" subjects. leading to male career opportunities and have been dissuaded from choosing these subjects at Advanced level because of teaching methods at GCSE level which in various ways discourage girls. It is notable, however, that Females are now more likely than Males to opt for A Level Chemistry and that increasing numbers of females have opted for A Level Business Studies which in 2022 entered the female top 10 A Level subjects for the first time and that increasing numbers of females are opting for Business and Management courses at university although males still predominate in this area. Similar factors operate to encourage male pupils toward Mathematics, Further Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry [although female entries have exceeded male entries for A Level Chemistry since 2018] Computing, Technology, Economics and Business Studies [although increasing numbers of Females are opting for Business Studies courses at A Level and University Level.

Nevertheless, within Sociology social action theorists have always tended to argue that the power of the socialisation process is rather weaker than has been suggested in structural theories and in theories focusing on postmodernity and high modernity it has certainly been suggested that individuals have become far more self-reflexive and more in control of the development of their own identities. Thus traditional gender differences in socialisation may now be smaller, especially perhaps in the case of academically successful [and mainly but not entirely middle class students] , that some attempts are being in schools to undermine traditional patterns of subject choice , that it has always been well known that good qualifications in Arts and Humanities as well as the sciences can open up good career opportunities for boys as well as girls and that an increasing number of females are now employed in occupations such as Medicine, Law and Business administration which were once dominated by men. These factors would help to explain any decline in traditional gender differences in subject choice at GCSE and Advanced Levels. Nevertheless, it is abundantly clear that significant gender differences in subject choice exist at Advanced level and that they are even greater in Higher Education. Explanations of Gender Differences in Subject Choice: A Brief Summary Gender differences in subject choice may be explained in general terms by the following interconnected factors:

. The significance of these factors may have altered significantly for some students but not others.

|