Russell Haggar

Site Owner

Chinese Pupils and Educational Attainment

Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement: Race, gender, class, and success [ Louise Archer and Becky Francis 2007]

Chinese students are the most successful of all ethnic groups within the British education system. In this document I present some recent DfE data which illustrate their success at Key Stage 4 level and their high rate of access to Higher Education followed by some summary information from Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement: Race, gender, class, and success [ Louise Archer and Becky Francis 2007] in which the authors analyse the educational attainment of Chinese students.

Click here for Educational Attainment at KS 4 2018/19- 2021/22 Also click here for data based upon a finer breakdown of ethnic categories. These data are also reproduced below .

Click here for FSM and ethnicity which shows that very few Chinese and Indian pupils are eligible for FSM based on official data..

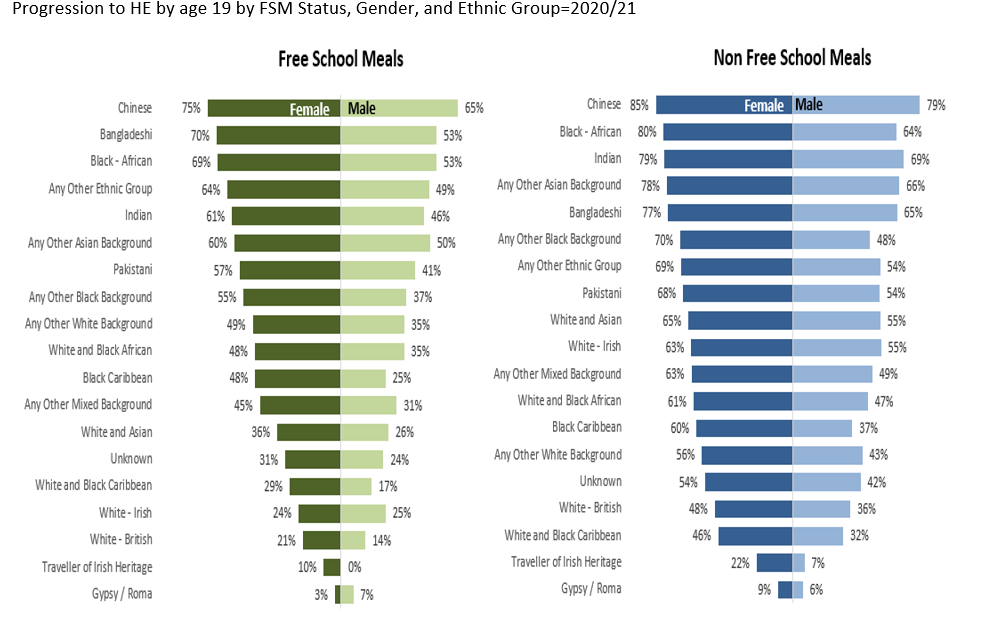

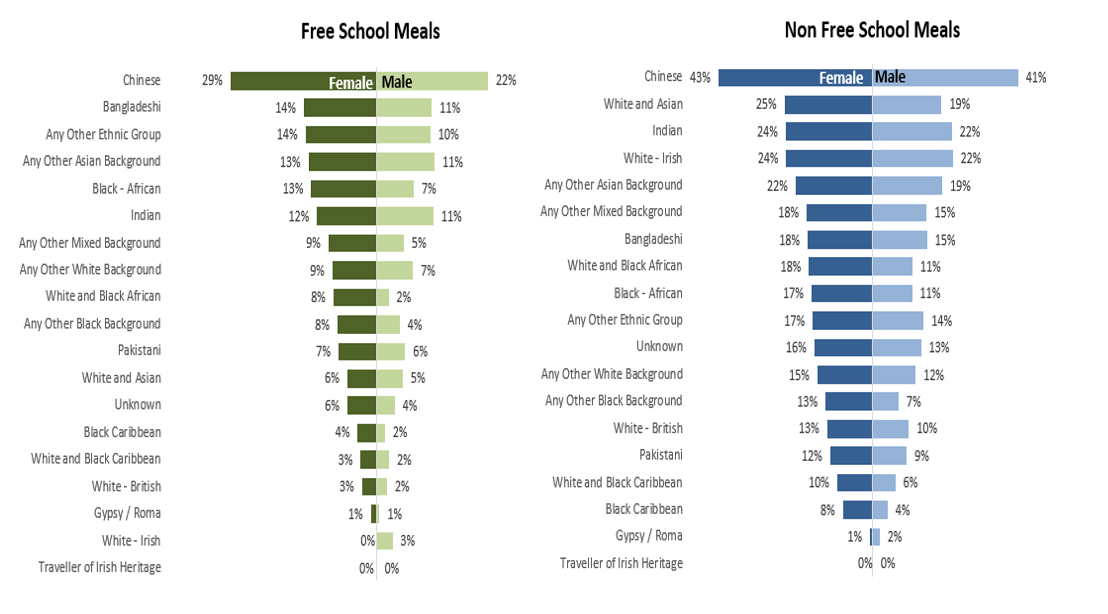

Click here and here for data from Widening Participation in Higher Education Academic Year 2020/21 on Access to Higher Education and to High Tariff Universities by Free School Meals, Gender and Ethnic Group. I have reproduced the diagrams below.

Progression to High Tariff HE

Progression rates to high tariff HE providers were highest for Chinese pupils regardless of gender or free school meal eligibility. This was particularly apparent for pupils who were eligible for free school meals where Chinese pupils were more than three times as likely as all other pupils to progress to high tariff HE.

Understanding Minority Ethnic Achievement: Race, gender, class, and success [Louise Archer and Becky Francis 2007]

[Also Click here for The Construction of British Chinese Educational Success: exploring the shifting discourse in educational debate, and their effects. B Francis, Ada Mau, and Louise Archer 2017]

In this study the authors conducted semi- structured interviews with 80 mainly second generation British Chinese pupils [48 boys and 32 girls] in years 10 and 11 in 26 London schools. The pupils’ parents had been borne mainly in Hong Kong but there were also interviews with some third generation British Chinese pupils whose grandparents had been brought up in mainland China. The schools included both mixed sex and single sex schools and were mainly comprehensive schools although 2 schools were independent selective schools. The pupils came from a wide range of social class backgrounds and 60% of the sample were from top and middle sets which ensured consistency with the national setting allocation for Chinese --origin children. The authors also interviewed 30 teachers [20 women and 10 men] most of whom were White British/English/UK from 19 schools and 30 Chinese parents/guardians [21 mothers and 9 fathers] all of whom were from Hong Kong.

The teachers interviewed had a positive although some what ambivalent attitude to both Chinese pupils and to their parents. The teachers were well aware that in general Chinese pupils outperformed pupils in other ethnic groups and explained this in terms of the high levels of parental encouragement which these pupils received and in their readiness to work hard to achieve their educational goals. They believed that Chinese boys were relatively likely to adopt a form of masculinity in which academic achievement and respect for parents were highly valued which meant that these boys were less likely to involve themselves in laddish behaviour. When they did so their misbehaviour was generally fairly mild and the teachers often explained this in terms of the Chinese boys’ associations with Black and/or white working class boys although the teachers also referred occasionally to Chinese boys’ interests in martial arts and even to their possible associations with triad gangs, [ associations which were probably overstated.]

The teachers’ positive assessments of Chinese boys and girls were often linked with negative [and stereotypical] assessments of both Black and White working class boys and girls. However, the teachers were also somewhat critical of Chinese pupils on the grounds that their approaches to education were considered to be overly conformist and lacking in the alleged flair and originality which teachers associated especially with white middle class boys who approximated most closely to the teachers’ image of “the ideal pupil”. Teachers also referred specifically to the quietness and passivity of Chinese girls.

The teachers’ attitudes to Chinese parents reflected a similar ambivalence. They recognised that Chinese parents valued education and emphasised its importance to their children and in some cases contrasted the attitudes of Chinese parents positively with the allegedly negative attitudes of Black and White working class parents. However, they also believed that these parents might pressurise their children excessively and that they were also unwilling to engage in an active dialogue with teachers around their children’s education or to make positive criticisms of school practices even when these might well have been justified.

The interviews with Chinese parents themselves indicated that Chinese parents in all social classes valued education highly and made strenuous efforts to improve their children’s educational prospects. Working class Chinese parents recognised that they had been held back by the inadequacies of their own education and believed that through educational achievement their children would have a more prosperous future. Chines parents from all social classes believed absolutely that hard work rather than inherent ability was the key to educational success, and they seemed to exhibit none of the fatalism which has sometimes [ not always accurately] been associated with white working class parents. Also, even if they were short of money Chinese parents were prepared to pay for individual private tuition ort to enrol their children in additional classes at Chinese weekend schools and if the parents ran their own businesses, they were prepared to work long hours so that their children could concentrate on their studies.

Chinese parents supported school objectives but, in some cases, had even higher expectations of their children than did teachers and the parents tended to believe that in the English school system discipline was somewhat lax and that pupils were not pressured enough to reach their full potential. Here we see some differences of opinion between the views of teachers and Chinese parents around the nature of the British education system. Also, the while the parents did encourage their children to prioritise their education, they also often showed a readiness to defer to their children’s wishes regarding choice of career which suggests that the teachers; may well have overstated the authoritarianism of the Chinese parents. The Chinese moms may not be as “tigerish” as has often been claimed!

There were few, if any, social class variations in the views of the Chinese pupils interviewed. They almost all recognised the importance of education and saw themselves as well motivated hard working pupils. They were fairly confident in their natural abilities and believed that their educational success or failure would depend very much upon how effectively they pursued their studies. They recognised the importance of parental encouragement but did not see parental pressure as excessive and commented upon their parents’ willingness to respect the pupils’ wishes regarding choice of career.

The Pupils’ views differed somewhat from the teachers’ views in that for example they were more likely than the teachers to admit the possibility that Chinese boys might engage in “laddish” behaviour although this was less frequent than in the case of Black and White boys and was more likely to be at a lower level and to derive from association with Black and White boys, The pupils also mentioned that Chinese boys were more likely to define their masculinity in terms of academic ability and in terms of respect for their parents: this was what it meant to be “a good son”.

Some Chinese pupils also expressed concerns that teachers had sometimes given them insufficient help because of a failure to recognise that Chinese pupils, just like other pupils could sometimes have difficulties with their studies and some Chinese girls denied the teachers’ opinions that they were especially likely to be quiet and passive in class.

Since the study was published in 2009 Chinese pupils have continued to make rapid progress at all levels of the British education system and the study illustrates that the reasons for the pupils’ success can be seen very clearly in the attitudes of the parents and of the pupils themselves. The pupils were also assisted to some extent by the positive views held by teachers of Chinese pupils’ academic abilities although the teachers in the study also tended to view Chinese parents as excessively authoritarian and the pupils as lacking in academic flair and originality in comparison with White middle class pupils. The authors did interview 30 teachers, but we cannot know whether their views were representative of the teaching profession as a whole. Hopefully not!